- Home

- Patrick Jones

The Tear Collector Page 7

The Tear Collector Read online

Page 7

“I’ll take care of things at school, if that’s okay with you,” I say, but that statement only leads to bewildered looks from both. Maybe my question forces Robyn’s parents’ realization of the hundreds of details to attend to, the thousands of conversations to have, and the millions of tears they’ll cry. Now they can’t find even one word—yes or no—to say. Before a tragedy, people think they know everything; afterward, they realize that so much of reality is just an illusion.

“I’ll talk to Mr. Abraham; we’ll organize something,” I add as they remain mute. “Everybody loved Robyn. They’ll need some way to show it.”

“Thank you, thank you for everything. You’re so giving,” Mr. Berry says as he hands me back my handkerchief that, at the last moment, he moistened with a few of his tough-man tears.

“I just want to do what’s best for everyone,” I say, thinking not just about this family in front of me, but also back at Veronica’s house. I go upstairs and say good-bye to Becca. I can’t look her in the eye because I know the storm that is coming. Part of me wants to stay for the suffering; I wonder if that part of me died with Robyn.

When I get home, everyone is sitting at the table. I want to run past them, but I can’t; they are my family. Instead, I pull the grief-stained handkerchief from my pocket and offer it to Veronica, who is feeling better, mostly thanks to me, and spending more time downstairs. Veronica takes it without a word or even a nod. I turn on my heel and head toward my room. But I get no farther than one step away when Mom calls after me. “What’s going on?”

Although we keep our secrets safe from the world, inside this house it is hard to hide anything from my family’s sixth sense. I look down, then mutter, “My best friend, Robyn, died. I think she killed herself.” I don’t add that even if I’m not to blame, I’m partly responsible.

As I walk away, I try to pretend I didn’t hear Veronica proclaim, “That’s just wonderful.”

CHAPTER 9

THURSDAY, MARCH 19

Why were you surprised?”

I direct the question back at Scott. I’m sitting in my bedroom in the twilight with the lights off, thinking about Veronica saying Robyn’s death was “just wonderful.” With just two words, everything I’ve known suddenly seems wrong. I was lost in brooding thoughts about family and friends, about betrayal and loyalty, when Scott called. After a first few awkward moments, we’re connecting. The talk turns to Robyn; it is all anyone at school is talking about.

“I was just surprised you came to school, that’s all I was saying,” Scott says in the tone of an apology. “Lots of Robyn’s friends, I noticed, didn’t come to school today.”

“I wanted to be there for people, I guess,” I say, telling more truth than he can imagine. The school was filled with waves of tears, and I rode every one. I spent most of the day not in class, but in public areas, like the library, providing comfort. By the end of the day, every friend of Robyn’s who came to school came to me. Many cried endlessly; I took their tears effortlessly.

“I should have been there for you,” he says.

“What do you mean?”

“Yesterday, in the car, I wasn’t much help.”

“Yes you were, Scott, you helped a lot.”

“Really?”

“Sometimes the best thing to do is nothing,” I say, knowing those words reflect badly back at me. I think of all the things I said—and didn’t say—to Robyn. I betrayed Robyn; I obeyed my family. I had no choice. There may be another Robyn, but I’ll never have another family. Yet, after Veronica’s words last night, I wonder if that reality might not be so bad after all.

“Well, if you do want to talk,” Scott says, “I’m a good listener.”

I laugh. Mostly guys only want to listen when you tell them how great they are. That was Cody; that was Tyler. I sense that’s not Scott. “Thanks, Scott, but that’s my job.”

“What do you mean?” he asks. I don’t respond right away, and he allows the silence.

I’ve said too much, but something about Scott pulls the truth—or as much truth as I can speak—out of me. Finally, I say, “I’m the one who listens to other people’s problems.”

“Then who listens to your problems?” Before I can answer, he laughs nervously and adds, “Never mind. I bet a beautiful, smart girl like you doesn’t have any problems.”

Silence surrounds me. I wish I could tell Scott my truth—a truth I’ve always known but that the events of the past few days have opened like a flower. I don’t have any problems; I am the problem. Scott lets the silence linger, which most guys won’t do, and then says, “I’m sorry.”

“Sorry?”

“I’m as smooth at this as broken glass,” he says.

“At what?”

“I’m trying to flirt with you,” he whispers. “I guess if I have to tell you that, then—”

I cut him off, yet pull him closer. “It’s not flirting if the person already likes you.”

“Really?”

“Really,” I say, and then the silence swallows again.

“So, do you want to go out sometime?” he asks, but before I can answer he adds, “Sorry, that’s rude. Your best friend just died and I’m asking you out. What must you think of me?”

“What I think of you,” I say without a pause, “is that I’ll see you Saturday night.”

After I hang up, I head downstairs to get a fresh bottle of water. In the past hour, I’ve heard both Maggie and Mom come home from working their usual ten-hour days. Earlier today, Veronica left the house for the first time in a while, but now she’s back in her room, waiting for me. This morning she didn’t say good-bye to me, and this evening, she won’t say thank you. So her last words that still echo are how she told me Robyn’s death was “just wonderful.”

Mom’s on the phone, no doubt handling last-minute arrangements for the family reunion. Maggie, sitting at the kitchen table, motions for me to join her. I stop but don’t sit down.

“How was school?” Maggie asks. “You could probably swim through the tears.”

“Most of Robyn’s other friends didn’t come to school today,” I report. “But tomorrow we’re doing a memorial service, so most of them will probably be there.”

Maggie smiles and says, “Veronica’s very pleased with you.”

“She shouldn’t be,” I say sharply. “It wasn’t my fault.”

“I know that,” Maggie says. “You’re a good girl, Cassandra, you follow the rules.”

I look away from her. As with doctors, the family rule is “Do no harm.” No harm directly. But it is through hurt that my family thrives. Since Maggie opened this door, I step in. “Unlike Alexei.”

“What do you mean?”

“There’s something evil about him. I just know it,” I say, finally telling her about my suspicions. Maybe I’ll go up to my room, unlock the desk drawer, and bring her the folder full of evidence.

“How dare you talk that way about your promised cousin,” she says.

“Don’t remind me.” Both Alexei and I turned seventeen this year. My family says they have plans for me, but they haven’t given me any specifics. I only know that it involves Alexei. So I’m pretty sure that whatever it is, it will be bad for me.

“You don’t have to like him,” she says. Love, of course, isn’t in our family lexicon.

“I loathe him,” I whisper.

“Cassandra Veronica Gray! He is family. How dare you talk that way?”

I pause, think of all the things I want to say, and then say them: “I hate him and this life we lead. I don’t want a family that’s happy when my friends die. I just want to be normal and—”

But she stops me with a hard stare and a hard slap of her hand against the kitchen table. “Cassandra, none of us chose this existence. No more than a worm chooses to be worm, a lion chooses to be a lion, or a human chooses to be a human. This is who you are!”

“No, it is not who I am!” I shout back. “It is what I am.”

�

�We are family!” she shouts. “We all have our roles. You have yours. I have mine.”

“And what is that?”

“Your role now is to produce the next generation,” is her horrifying reply.

“And what if I don’t want to?”

“You don’t have a choice,” she says in a tone that sucks all the moisture out of the air.

“Then explain Siobhan,” I say, hissing the forbidden name of the family exile.

“I don’t know anyone by that name,” she says as she rises from the table. She walks toward me and points her finger at me. “I don’t know anyone by that name, and neither do you.”

Maggie starts to walk past me, but I take off running in a different direction. I’m sitting on a curb at the end of the block dialing my phone before she’s probably climbed the first stair.

“Siobhan, it’s your cousin Cassandra.” The phone shakes in my hand as I speak into it.

“You’re not supposed to call me,” is her less-than-friendly greeting.

“I know, but I don’t have anywhere else to turn.”

“What about Lillith or Mara?” she asks, naming my two other favorite cousins.

“They don’t understand,” I say. “They accept it.”

She doesn’t ask what “it” means. It is the life we lead. “No one knows you’re calling?”

“I’m down the street,” I say. “They don’t know where I am. They don’t care.”

“You’re wrong, Cassy; they care very much.” I smile at hearing her nickname for me; it reminds us both of our connection. “I’ve hurt the family too much already. I can’t talk to you.”

“Can’t? What do you mean?”

“I’m out of the family. It’s all in the past,” she says. “I can’t get involved. It’s wrong.”

“But I have to tell you something, and it’s important,” I say. “Please, I’ve got no one else.”

There’s a long pause on the other end of the line until she finally says, “Okay, Cassy.”

“My best friend, Robyn, died.”

“What happened?”

I tell her a short version of Robyn’s death, focusing on the rumors, not mentioning my hand in any of it. But my hands aren’t clean; they still feel very damp with her blood.

“She killed herself?” Siobhan asks. I start to answer but instead I pause, letting a million thoughts in my head crash like waves on the beach. “Please don’t tell me that you—”

I interrupt. “I wasn’t in the car when she drove too fast. I didn’t do anything directly.”

“You’re sure?” She seems skeptical.

“I did not,” I say firmly. “But it was my fault. I know it was my fault.”

“What did Veronica say?”

I pause, not wanting to repeat the words. “Let’s just say it was beyond cruel.”

“Get used to it,” Siobhan says. “That is what your life is going to be like.”

“I know,” I say, wishing the stars above could swallow me. “Is that why you—?”

“Got out,” she says. “That’s part of it.”

“Can you tell me how?” A five-word question that holds infinite possibilities for me.

“I can’t tell you that, Cassy,” she says. Regret drips in her voice.

“Why not?”

“Because part of it is figuring it out for yourself,” she says. “I’m not the first. Others have left, but life becomes hard in a different way. I know you don’t want to hear this, but your life is easy. The hardest thing in the world to do is love. You don’t need to worry about that.”

“But I want to!” I shout. “I want to fall in love. I want to be normal. I need to know!”

“Cassy, listen. I understand what you’re going through,” she says. “Everybody goes through this. Everybody pushes through it, and life goes on. Everybody fills their role—”

I cut her off. “But you got out.”

“Yes, because I allowed myself to fall in love,” she says. “But I’ll always regret what I had to do to get out. And now that I am out, I’m an orphan. I have no family to protect me.”

“But you have love,” I say. “And you have a life that’s not filled with tears.”

“You’re wrong about that,” she says, almost laughing. “There’s a difference.”

“What’s that?”

“The tears are all my own now.”

“I don’t understand,” I say. “I thought love made you happy.”

“And anything that makes you happy can make you sad,” she says. “Cassy, look, I can’t talk to you. I betrayed our family once; I can’t do it again. I can’t help you.”

“Just tell me one thing!” I shout. “Please, just give me a hint, anything.”

Another long pause. “Okay, but after this, you can’t call me again. I’m out of this.”

“I understand,” I say. If you got out of jail, I suspect you’d never want to see iron bars again.

There’s a pause, then she says, “Cassy, the hardest choice is the first choice.”

“What do you mean?” I ask, even as the school bell rings across the street.

“The first choice,” she finishes, “is realizing you have a choice.”

CHAPTER 10

FRIDAY, MARCH 20

What do you want us to do?”

Brittney and I are both staring at Mr. Abraham. It has been about forty hours since Robyn’s death, but it is only five short minutes before the memorial gathering at school. I’m waiting for an answer to my question about what to do, both right now and from this day forth.

“This isn’t what she would have wanted,” Brittney says in her best fit-throwing voice.

“It’s too late to change everything,” I tell her, but I’m focusing all my energy on Mr. Abraham. He, along with the peer counselors and school counselors, quickly organized this event. The theater auditorium is filling with traumatized students, but all the drama is backstage.

“You should have involved us,” Brittney says. She’s the spokesperson for Robyn’s cheerleader friends. Like everyone else in school, their reaction to Robyn’s death has been to walk around school like ants with a dead queen. “This should be upbeat, like Robyn was.”

“This is a memorial service, not some kegger,” I say, sharply and directly.

“We should be celebrating Robyn’s life, that’s what she would have wanted,” she says.

“This isn’t just about Robyn, this is about everybody left behind,” I say. “What Robyn would have wanted and how she lived was to focus on other people. Her friends need to heal.”

“That’s sick,” Brittney says.

“That’s enough, both of you,” Mr. A finally says, then sighs. He sips from his thermos, then says, “One thing’s for sure, Robyn wouldn’t want her friends fighting.”

Both Brittney and I let that go. For now. Robyn was able to keep our rivalry in check, but if Brittney says one more word, then I’ll bring up Craig and force her guilt down her throat.

“Brittney, I will help you plan something next week to be a celebration of Robyn’s life,” he says, as I try to hide a victor’s smile. “But there’s a process to grieving, and a memorial service like this—where people can openly grieve—is important to students healing and moving on. I wish we had more time to plan, but it’s essential we do something before the weekend.”

“I knew it,” she hisses.

“I’m sorry, but we’ll continue with the program that Cassandra and the counselors have planned,” he says. “I hope you will still say something as you agreed.”

“I’d do anything for Robyn,” Brittney says, trying to play the part of the martyr.

“Haven’t you done enough?” I say. She stares daggers and I welcome the cuts.

“Brittney. This is difficult for everyone, especially her friends like you and Cassandra,” Mr. Abraham says. He’s one of the smartest people I know. Why can’t he see through her?

“I was her best friend,” Brittney says, treat

ing this occasion like a fight on the playground. I’ve never felt the deep dark human emotion of hate, but it’s emerging now.

“If that’s the case, then—,” I start, but I feel a hand on my shoulder. I turn around to see Dr. Albrecht, the school’s main counselor.

“Cassandra, Brittney, please,” she says. “I know this is hard for everyone.”

“Then why isn’t everyone here?” Brittney asks, sneaking a peek through the curtains. Dr. Albrecht decided to open the memorial service to anyone who knew Robyn and wanted to attend. I wanted it to be for everyone at school, but Dr. Albrecht said that wasn’t the best way.

“Brittney, everybody in this school is changed by a student’s death, I understand that,” she continues. “But not everyone handles grief the same way. Some people grieve in private, some need to be around others. The thing we don’t want to do is force students to behave one way or the other. You’ll find all sorts of reactions from people.”

“I understand,” Brittney says, although I doubt she really does. When you spend half your life taking pictures of yourself, how can you even begin to understand other people?

I look through the curtains to see the room filled with students from across the spectrum, although it is mostly Robyn’s fellow juniors.

“Brittney, there’s no one right way to handle the death of a popular student,” Dr. Albrecht says. “We’re doing our best. We’re arranging for extra counselors to come in to talk with students, and we have done some extra training for students in the peer counseling program.”

“The moment of silence yesterday was nice,” I say, sucking up to Dr. Albrecht.

“This is hard on everyone, but what makes it harder is people fighting about who was whose best friend, or things like that,” Dr. Albrecht says, making sure to make eye contact with both of us. I hang my head in mock shame, while Brittney pretends to cry. I sense false tears.

“And people will feel guilty,” I say as I admit to a new emotion, even as I accuse Brittney. “They’ll wonder if Robyn would still be alive if they had done—or not done—something.”

Head Kick (The Dojo)

Head Kick (The Dojo) Duty or Desire

Duty or Desire Returning to Normal (Locked Out)

Returning to Normal (Locked Out) Things Change

Things Change Controlled

Controlled Friend or Foe

Friend or Foe Stolen Car

Stolen Car Heart or Mind

Heart or Mind The Franchise

The Franchise Triangle Choke (The Dojo)

Triangle Choke (The Dojo) #1 Out of the Tunnel

#1 Out of the Tunnel Chasing Tail Lights

Chasing Tail Lights Nailed

Nailed Combat Zone

Combat Zone Outburst

Outburst Barrier

Barrier Fight or Flee

Fight or Flee Doing Right (Locked Out)

Doing Right (Locked Out) Cheated

Cheated Guarding Secrets (Locked Out)

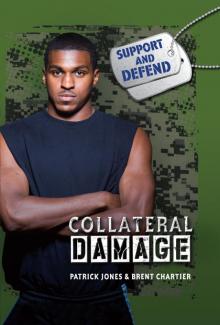

Guarding Secrets (Locked Out) Collateral Damage

Collateral Damage On Guard

On Guard Always Faithful

Always Faithful The Gamble (Bareknuckle)

The Gamble (Bareknuckle) Side Control (The Dojo)

Side Control (The Dojo) Bridge

Bridge Body Shot (The Dojo)

Body Shot (The Dojo) The Tear Collector

The Tear Collector Slammed

Slammed Drift

Drift Pass It Forward

Pass It Forward Target

Target Freedom Flight

Freedom Flight Taking Sides (Locked Out)

Taking Sides (Locked Out)