- Home

- Patrick Jones

The Tear Collector

The Tear Collector Read online

The

Tear Collector

….

Patrick Jones

….

CONTENTS

Cover

Title Page

Dedication

News Report #1

Chapter 1 Friday, March 6

Chapter 2 Saturday, March 7

Chapter 3 Sunday, March 8

News Report #2

Chapter 4 Monday, March 9

Chapter 5 Thursday, March 12

Chapter 6 Saturday, March 14

News Report #3

Chapter 7 Monday, March 16

Chapter 8 Wednesday, March 18

Chapter 9 Thursday, March 19

Chapter 10 Friday, March 20

News Report #4

Chapter 11 Saturday, March 21

Chapter 12 Tuesday, March 24

Chapter 13 Wednesday, April 8

News Report #5

Chapter 14 Thursday, April 9

Chapter 15 Friday, April 10

Chapter 16 Saturday, April 11

Chapter 17 Sunday, April 12

Chapter 18 Wednesday, April 15

News Report #6

Chapter 19 Monday, April 20

Acknowledgments

ALSO BY PATRICK JONES

Imprint

To Laura and Kim for their continued support

The law of conservation of energy

states that energy cannot be created or destroyed;

it can only be changed from one form to another.

Other animals howl when they are in distress,

but only humans weep tears of sorrow—or joy.

—Chip Walter, “Why Do We Cry?”

Scientific American, November 2006

Jesus wept.

—John 11:35

NEWS REPORT #1

Michigan State Police have issued an AMBER Alert for eleven-year-old Robert Sanders. Sanders, a fifth-grade student at Bay City Elementary, was last seen leaving school on March 4. According to witnesses, he was walking home alone. Law enforcement officials are on the lookout for a black Ford van seen in the area earlier in the day.

CHAPTER 1

FRIDAY, MARCH 6

Are you crying?” I ask as I tap on the driver’s side window of the white Chevy Impala. Inside the familiar car, I see the unfamiliar sight of my best friend, Robyn Berry, crying.

“Robyn, it’s Cassandra,” I say. It’s a wonder she can see or hear; she’s drowning in tears. She takes a second to collect herself, then opens the window. With her perfect makeup smeared, it’s as if she’s wearing a monster mask instead of her always-smiling cheerleader face.

“Hey, Cass,” she forces out through sniffles.

“Let me in,” I say, gently enough so she knows I care; hard enough to make it happen.

Robyn clicks the lock, and I walk over to take my usual seat next to her.

“Are you okay? Why didn’t you call?” I ask as I climb in. It’s odd to see Robyn without her silver phone in her hand or white buds in her ears; both are almost part of her.

She doesn’t answer as I sit down, then lean close to her. I offer a sip from my water bottle, but she passes. I take a big slurp, parched from a hard hour of swimming, thanks to Coach Abraham opening up the pool after school. After a quick stop to print something at the library, I was on my way home when I saw Robyn’s car at the back of the school parking lot.

“It’s okay to cry, Robyn,” I say softly, encouraging another emotional outburst. She listens, letting loose a torrent of tears. I slip off my jacket—actually my soon-to-be-ex-boyfriend Cody’s varsity jacket—then pull her close, letting her tears fall on my bare left shoulder. I’m wearing a simple gray tank top set off by the tie-dyed bandanna holding back my long multicolored hair. My hair is like my life: mostly dark, but with a few streaks of light and color added in.

I don’t say anything; instead, I let her cathartic tears soak into my skin. After a few minutes, she pulls herself together and retreats toward her side of the car. Lapeer High School runs on rumors, and someone seeing two girls hugging in a car is inviting gossip, lies, and drama. Who is and isn’t pregnant, gay, bi, or hooking up keeps the rumor tides ebbing and flowing.

“Thanks, Cass,” she says, then sniffs to signal an end to this round of eye rain.

“Like that Beatles song says, you get by with a little help from your friends,” I tease. I turned Robyn on to the Beatles, while she’s always trying to get me to listen to the latest big thing. That’s why Robyn and I are such good friends; we make up for each other’s deficiencies.

She still doesn’t say anything, so I ask, “What’s wrong?”

“Everything,” she answers, which sets off a few more drops of liquid despair.

“Something with Becca?”

“No, she’s fine,” she says, even as her brief nervous laughter dissolves into almost mandatory tears. Becca is Robyn’s younger sister. She’s eight and she has cancer, so she probably won’t turn nine.

“She’s a fighter,” I say. Robyn forces a smile; there’s a lot of faking in the face of death.

Becca’s the glue that holds together our friendship. I didn’t know Robyn well until last spring, when I learned about her sister through my volunteer work at the hospital. I knew Robyn would need a friend like me who could comfort her rather than all those selfish hanger-on types who feed off her, like Brittney and Kelsey. Like me, Robyn’s popular. She cruises easily among everyone, but as a cheerleader, she’s got her main crew. I’m all over, like a sponge soaking up friends from all cliques. But I’m always there for Robyn, to listen to her problems or babysit Becca so Robyn can hang with her superficial friends. She’s again learning—as have others at Lapeer High since ninth grade—that I’m the soft shoulder that anyone can cry on during hard times.

“Craig dumped me,” she says, each word pulled out of her with great pain like a tooth extraction. He’s the perfect jock boy for the cheerleader Robyn. Craig’s just like her: attractive, outgoing, and admired. Robyn would be popular without Craig, but he’s the icing on her cake. They’re not just students; they’re stars, but Robyn’s the falling one. I’m here to catch her.

“Robyn, I’m so sorry,” I say, trying not to stare at the small photo of the once-happy couple hanging from the Impala’s rearview mirror. Like that mirror, the photo reflects the past.

“I don’t want your pity,” she says. “I don’t want to be pitiful.”

“Why would he do that?”

“Kelsey told me he was cheating. He denied it, we fought, then he ended it. He said we were over,” she says. “Craig is the center of my world. If he’s gone, then it all falls apart.”

“I’d heard rumors too,” I mumble. She mouths the word “what” as if she doesn’t have enough energy to produce any sounds other than sobbing. “It was true. He was cheating on you.”

“Tell me what you know.” She’s pleading now.

“I heard it was Brittney,” I whisper, since that’s the tone for spreading a rumor. While I’ve got experience breaking hearts—as cute but clueless Cody’s soon to learn—I couldn’t tell Robyn what I’d heard. It is one thing to watch someone suffer; it is another to be the direct cause.

“How could she do that?” Robyn asks. “She’s one of my best friends.”

I don’t correct her. At school, Robyn mostly hangs out with Brittney, but it’s different away from Lapeer High. From babysitting her sister to eating dinner with her family, I mean more to Robyn than Brittney does. Brittney’s all smiles and surface. Brittney clings to Robyn’s spotlight and shadow while I’m the drain for the despair and doubt that Robyn hides.

“How could Craig dump me for her?” Her wet eyes stare into mine, but the question isn

’t aimed at me. It’s like she’s asking a higher power to explain the unfairness of the universe.

“She’s supposed to be your friend,” I say.

“How could he?” she mumbles. “How could she?”

“I’m your true friend, not Brittney. Have faith in me,” I say, then move closer. I finger the three necklaces pressing against my skin and that signify my beliefs. Except when I swim or take a quick shower, I’m never without my trinity of faith: a peace-sign button on a hemp string, a gold crucifix hanging from a gold chain, and a silver necklace with a crystal teardrop charm.

“Craig said he loved me,” she says while avoiding my sympathetic eyes. She doesn’t know that’s all I offer: sympathy. I have no empathy for her, or for anyone else suffering from a broken heart. I can no more understand love than a blind person can comprehend color.

“I guess he lied,” I say.

“How could he not want me?” Robyn asks the universe through me. She’s struggling with her words like a rookie actor onstage. Words of rejection and failure are new to Robyn.

“Everybody knows you’re wonderful and he’s a jerk,” I remind her.

“Once people hear, they’ll be laughing at me,” she says. “People want me to fail.”

“Come on, Robyn, nobody will laugh at you,” I say. “Everybody loves you.”

“No, people hate me, I know it,” she says with a hiss. “They’re jealous.”

“Don’t say that,” I say, but I don’t deny it. People are jealous of her outwardly perfect life, including me. Envy, anger, and fear are the only emotions I feel deeply; others I only fake. Yet, even as I see Robyn suffer because of love, I know it’s the one emotion I want for myself.

“It’s not my fault I’m pretty,” she says. With her blond hair, blue eyes, and faultless figure, every straight guy wants her. Yet because she’s nice and never stuck-up, most girls envy her, but none outwardly hate her. “I didn’t ask to be popular.”

“I know, it is just who you are,” I say. She’s popular because she’s pretty and good at talking to people; I’m popular because I’m pretty enough and great at listening to people.

“I work hard in school and everything else,” Robyn says through more tears. The breakup has broken down her self-control. “I have to be the best. It’s my nature.”

“Do you want me to drive you home?” I ask, very tentatively. As one of the few juniors at Lapeer High School without a car, my time behind the wheel is limited. I have a license indicating Michigan trusts me to drive, but I have a mom who doesn’t share the state’s faith.

“I don’t want to go home,” Robyn says, still whispering like there’s no energy left in her body to speak. “I can’t take another thing. Everybody there wants so much of me.”

“I understand,” I say. While I identify with family obligations, it’s not the pressure to succeed that Robyn feels from her engineer dad and lawyer mom. Her parents want their daughter to succeed, but what Robyn hears, I think, is she isn’t allowed to fail. Add in cheerleading, honors classes, and being the perky popular girl, and it’s a mix that would break most normal human beings.

“And I can’t tell anyone how hard it all is.”

“You can tell me,” I say, then remind her of my mantra. “You can trust me.”

“I want to be able to tell my parents that it’s all too much. With Becca, they have so much to worry about,” she says, and the tears start to fall again. “Sometimes I think it would be better if I were dead.”

I don’t respond; instead, I let more drops soak into my shoulder and I feel a rush from the energy in the tears, probably the way an addict feels getting his fix from his drug of choice.

When I’m so full that I’m almost disoriented, I take a monogrammed white linen handkerchief from my back pocket. I gently transfer the tears from her face to this old-fashioned yet invaluable family heirloom. I pull her close, so she can’t see the smile forming on my face as a waterfall of tears continues to cascade from her eyes. Robyn needs to cry, but what she doesn’t know—and nobody outside of my family could imagine—is that I need her to cry even more. Just as a vampire needs to suck blood to live, I need to collect tears in order to survive.

CHAPTER 2

SATURDAY, MARCH 7

Can I help you?”

“I’m looking for the chaplain’s office,” the older man responds to my query in a dazed voice. He’s shell-shocked, standing in the safe bright hallways of Lapeer Regional Medical Center. It’s a look of loss: lost not in the building but in his grief. I see that look a lot here.

I walk him over to the map on the wall, then give directions. He tries to force a smile, but I can tell it’s too hard. “Happy to help,” I say as he walks away. Other than in the maternity ward, hospitals don’t birth many smiles. This is a place of death, sickness, and sorrow.

I’ve been a volunteer at the hospital since we moved to Lapeer. Over the past two-plus years, I’ve worked every Saturday unless I’ve had a swim meet, church, or family obligation. On Sundays, I do double shifts after Mass. During the summer, I put in even more hours. Now that swimming season is over, I can volunteer two more nights a week. When I started, like all new volunteers, I did boring stuff and didn’t interact with patients or families. Now the staff trusts me. They’ve seen how good I am at comforting people, so they bend the rules. I spend most of my time up in Pediatrics. It was there that I found out about Robyn’s terminally ill sister, Becca.

I walk back to organize my cart when I hear, “I heard you’re breaking up with Cody.”

I turn to see Kelsey, another volunteer adorned in the standard white button-down blouse and black dress pants of the hospital volunteer uniform. Like me, Kelsey’s a junior and a swimmer. We also share the same history class, Robyn’s friendship, and another common experience. She’s dating Tyler Adams, one of my ex-boyfriends, so we’re natural enemies. “Who told you that?” I ask.

“Everybody knows,” she snaps back.

“It doesn’t involve you,” I counter, but don’t deny it. For once, this bit of backstabbing gossip isn’t a lie. Now I understand why Cody’s been texting me like crazy all day. I won’t text or call him back. Cody knows my rules: breakups, like make-outs, must occur in person. If he wants to fight or fool around, he needs to let me stare into his dark brown eyes.

“Why do you care?” I ask, then start to walk away.

“How many hearts do you plan on breaking?” Kelsey asks, all sarcastic.

“Tyler’s only going out with you because you remind him of me,” I fire back. I hate angry conflicts; I have enough of them at home. I don’t need Kelsey sapping my strength.

“You wish,” she replies, but without much confidence.

“You know I’m right,” I say, then start again to walk away. In some ways, looking at Kelsey is like looking in a mirror. We’re the same medium height with the similar lean-but-mean female swimmer body type. I’m thinner and smaller everyplace, but I have no trouble getting attention. Kelsey sports a short blond hairdo, but I let my locks grow long so my tricolored hair (natural black tinted with red and yellow) tickles my exposed shoulders. With Kelsey’s tight clothes turning her cleavage into an eye magnet, no boy’s looking at her hair anyway.

“You’re so weird,” she says, the all-purpose high school put-down.

I sigh, then turn again to face her. “And you’re so normal. Tyler will tire of you soon enough. He’ll be afraid the dullness will wear off on him.”

She leans in toward me, then whispers, “Well, unlike Cody, at least Tyler gets off.”

“Whatever,” I say, and sigh. She’s guessing, which accounts for most gossip. Rumors are lies that sometimes turn out to be true. I think that’s what happened with Robyn and Craig. The word was Craig hooked up with Brittney. So, maybe they figured they might as well act on it. I don’t know, just like I don’t know who started the rumor, but I do know that Kelsey spread it like the plague.

“What did Tyler tell you about me?” I

whisper back, then take a sip from my water bottle. All these heated words are drying out my mouth.

“You’re a virgin,” Kelsey says, and I breathe a sigh of relief if that’s all he said.

I sigh loudly, then announce, “It’s none of your business.”

She laughs, which draws unwanted attention from the nurses’ station. I want to get away from Kelsey and get back to work. I couldn’t bear to get fired; this volunteer job sustains me.

“Cassandra, at Lapeer, everything is everybody’s business,” she says, reminding me of the hard truth of high school. I know I have a reputation as a heartbreaker, but it hasn’t hurt me yet. I’ve broken up with Cody before, but we bounced right back. There was shouting (me), followed by tears (him). We’d make up, make out, and break up again. But this is probably Cody’s last ride. Like Tyler, he’ll find somebody else. So will I. I always do, which is why I’m always looking.

“I have things to do, don’t you?” I snap, but Kelsey’s not moving.

“I don’t know how you can work here.”

“What do you mean?” I ask her, then pull out some lip balm. She’s really drying me out.

“The doctors here pledge to do no harm, but that’s all you do,” she says, and hisses.

“I’m here to help people, not hurt them.”

“Don’t be all like that,” she counters. “I see through your helpful-friend act.”

“What are you talking about?”

“Pretending like you care about anyone that is hurting,” she says. “Like how you’ve used Becca to become Robyn’s best friend over Brittney and me. It makes me sick.”

“No, it makes you jealous,” I snap back instead of admitting she’s right. With my great-grandmother Veronica’s failing health and her needing my help, it’s like this past year I’ve been on sympathy steroids. My first two years at Lapeer, I offered my shoulder only to friends, but this junior year, I’m looking for anyone who is hurt. Kelsey’s right; I’m a heartache whore.

Head Kick (The Dojo)

Head Kick (The Dojo) Duty or Desire

Duty or Desire Returning to Normal (Locked Out)

Returning to Normal (Locked Out) Things Change

Things Change Controlled

Controlled Friend or Foe

Friend or Foe Stolen Car

Stolen Car Heart or Mind

Heart or Mind The Franchise

The Franchise Triangle Choke (The Dojo)

Triangle Choke (The Dojo) #1 Out of the Tunnel

#1 Out of the Tunnel Chasing Tail Lights

Chasing Tail Lights Nailed

Nailed Combat Zone

Combat Zone Outburst

Outburst Barrier

Barrier Fight or Flee

Fight or Flee Doing Right (Locked Out)

Doing Right (Locked Out) Cheated

Cheated Guarding Secrets (Locked Out)

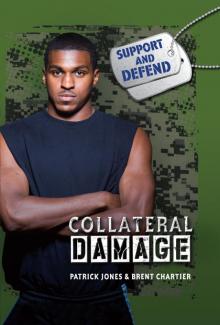

Guarding Secrets (Locked Out) Collateral Damage

Collateral Damage On Guard

On Guard Always Faithful

Always Faithful The Gamble (Bareknuckle)

The Gamble (Bareknuckle) Side Control (The Dojo)

Side Control (The Dojo) Bridge

Bridge Body Shot (The Dojo)

Body Shot (The Dojo) The Tear Collector

The Tear Collector Slammed

Slammed Drift

Drift Pass It Forward

Pass It Forward Target

Target Freedom Flight

Freedom Flight Taking Sides (Locked Out)

Taking Sides (Locked Out)