- Home

- Patrick Jones

Cheated

Cheated Read online

CHEATED

Patrick Jones

Contents

Cover

Title Page

Dedication

Part One

6:30 a.m.

7:00 a.m.

8:00 a.m., Homeroom

First Period

Second Period

Third Period

Fourth Period

Lunch

Fifth Period

Sixth Period

Seventh Period

After School / 3:00 p.m.

4:00 p.m.

5:00 p.m.

6:00 p.m.

7:00 p.m.

Part Two

9:30 a.m.

Part Three

9:00 a.m.

Acknowledgments

Also by Patrick Jones

Imprint

To Brent

Two roads diverged in a wood, and I—

I took the one less traveled by,

And that has made all the difference.

—Robert Frost, “The Road Not Taken”

Yes, there are two paths you can go by, but in the long run

There’s still time to change the road you’re on.

—Led Zeppelin, “Stairway to Heaven”

November 18, 9:00 a.m.

“It’s really simple, kid,” the investigator barks at me from across the table. He’s trying to scare me. “The one who talks is the one who walks. So, I’ll ask you the same thing I did when you came in here four days ago. What happened on November fifth?”

I’m trapped in an impossible situation. He’s asking questions, but I’ve got no answers I can give—yet there’s so much I want to say. My mind is a mess, littered with fear of the future, thoughts of the past, and one nagging question: how did my fifteen years of life lead me to staring death—in the form of a bloody dead body—in the face?

Part One

Friday, November 5

6:30 a.m.

I woke up that morning under dry sheets to the smell of coffee in my nose, the taste of cotton in my mouth, what felt like a brick smashing inside my skull, and a burning feeling in my gut. But not a single midnight memory of Nicole Snider resting in my brain. I was cheated even in my dreams that morning, never knowing, of course, that the day itself would end in a nightmare.

I turned off the buzzing alarm busting my eardrums, then buried my not-handsome-enough face into the soft pillow. I wanted to suffocate the thoughts of another day—although Fridays were the best day in my Nicole-less life. Friday was the day my best buds, Brody and Aaron, and I all told our moms we were going to the Swartz Creek High School football game. Instead, we’d hang at Aaron’s sister’s trailer drinking Bacardi 151, shooting the shit, and playing poker.

We’d started one night earlier than usual, at Aaron’s suggestion, and I was paying the price. I crawled out of bed as if my feet contained all of my five ten, 160 pudgy pounds, and wanted to vomit. It made me wonder if it was called “hungover” because I’d spent the night with my head hung over the toilet trying to vomit. But here, too, I was a failure.

My stomach felt queasy, but worst was a headache aggravated by any noise, even the sound of the piss splashing into the water hurt my head. I reached into the medicine cabinet and pulled out a bottle of aspirin. I swallowed straight two round white clouds of relief and horded four for later in the day. When I brushed my teeth, I looked into the mirror and wondered what day I’d start shaving, what week the zits on my chin would disappear, and what month I’d look more like a man instead of this fifteen-year-old awkward mass of flesh, nerves, and want. I spat out disgust at myself with the toothpaste, then stumbled into the kitchen.

My mother was wrapped in an oversized white sweater and curled up on the kitchen floor sitting next to the heat vent, Kool in one hand, coffee in the other. Her bare face showed little signs of life, love, or the pursuit of happiness. I avoided her eyes, then looked through the faded yellow drapes at the frost-kissed leaf-covered backyard as she spoke. “Good morning, Mick.”

I grunted, then grabbed milk from the fridge and poured a half glass. Maybe it was the distraction of my broken heart more than my throbbing head, but my hands didn’t work, and I spilled milk on the counter. “Sorry,” I said. I said that word a lot to everyone.

“Accidents happen,” Mom said, as she moved from the floor, then walked toward me. She cleaned up my mess while I snatched the Rice Krispies box from the sparse cupboard. Except for buying fast food, neither shopping nor cooking were Mom’s strengths. “Are you okay?”

I grunted, but I wanted to say, No, Mom, I’m not okay and you’re not okay, but let’s keep lying to each other since the truth hurts. I wanted to tell Mom a lot, but I couldn’t say the words. I spent more time imagining conversations with her, and others, than I did having them.

“When did you get in?” she asked as I successfully poured milk into the cereal bowl.

“About ten,” I mumbled. About ten after eleven was the truth, but I knew Mom had had a rare date after work, so she didn’t get home until after midnight. My lie was safe, if unsound.

Mom sipped her coffee, then spoke. “Are you going to the game tonight?”

“I’m taking the booster bus with Brody and Aaron.” I offered up the lie for her to challenge, but she let it go with a little half smile. She didn’t like my friends, but didn’t comment, unlike ex-Dad. He lectured me to “stay away from those who drag you down.” I took ex-Dad’s advice to heart and saw as little of him as possible.

“So, homecoming’s next week,” Mom said after an awkward quiet. My house seemed like a funeral home with all these long moments of silence. Even if I wanted to talk more to Mom, I couldn’t because she was either working or too tired from working so many hours. She managed this snotty Chico’s clothing store at Genesee Valley Mall. Outside the house, Mom always dressed in their private-label outfits, accessorized by her disappointed frown caused by her unkempt fashion-challenged son.

“I guess,” I said in between swallows, but I wanted to say, I know stupid homecoming is next week. You can’t walk two feet at school without some prep or jock talking about it like it was the center of the universe.

“Are you going to the homecoming dance?” Mom asked. I slurped down some milk, but wanted to say, I had a chance to go with Nicole, but I screwed it up. I don’t ask you about your boyfriends, so stay out of my love life, or lack thereof.

“Probably,” I mumbled my half-truth so she could only half hear it.

“You taking that Snider girl?” Mom doesn’t know Nicole broke up with me on the first day of school; she doesn’t know that I’m broken apart. The question was tentative; this was more of a conversation than we normally had. I wished there was a TV in the kitchen. I could have turned it on, and we could have watched other people talk to one another instead.

“No,” I whispered as the cracking popping snapping cereal crashed into last evening’s rum and Coke. I felt sick to my stomach, but sicker in my lonely boy circumstances.

Mom sighed, then spoke. “It’s a little late to ask someone else out, don’t you think?”

I rinsed out the bowl and the glass, but not the bad-tasting feeling that truth or lie, I was disappointing my mom either way. “I don’t want to talk about it!” I shouted as I left the room.

“Fine,” she snapped at me before she took a final drag and burned down the last hot embers on the Kool.

“Fine!” I shouted over my shoulder, but regretted that immediately. I wanted to say, Mom, I’m sorry. You don’t deserve this crap. I want to be a better son, but I don’t know how.

“One day you’ll talk to me.” Her words bounced in my head, like a silver pinball at Space Invaders arcade. I wanted to turn around and admit my helplessness. Mom, I want to talk to you so you can

tell me what to do, but there’s a wall and I just can’t smash through it.

Instead, I said nothing and retreated to my room, slamming the door behind me. I pulled cleaner clothes from the pile on the floor and got ready for school. I thought about wearing something other than my usual blue jeans and black T-shirt to impress Nicole, since she was now with that well-dressed college-bound bastard Kyle Miller. Yet I knew even if I changed my clothes, it wouldn’t have made Nicole change her heart or her mind. I wanted to confess to her how I felt, how I deserved another chance, and how I wouldn’t mess it up this time. But deep down, I knew I was lying to myself, as I often did. I can’t even tell myself the truth, and admit it was all my fault. As I headed toward the shower that morning, I thought about turning the water on superhot. I wanted to burn away a layer of skin and scorch away my old self. I needed to become someone else; someone who wouldn’t cheat or be cheated again. Nicole and I broke up because I was the one who cheated. How could I have known then that split-second decision would start me down a winding road filled with fire, smoke, and blood?

If you were looking at life in prison, then wouldn’t you take a long look at your life?

Even if, like me, you’ve only lived life for fifteen years. My mom made me watch a movie once called Forrest Gump. The guy in the movie keeps saying how life is like a box of chocolates, and you never know what you’ll get. Even I know boxes of chocolates have those diagrams on the bottom that show you what’s inside. No, life isn’t like that at all. You want to know what life is like? You ever see a road map of the United States? That’s life. It’s a thousand possible roads, all of them somehow connected to each other. Some roads take you places where you can roll down the windows, let the music blast, and drive forever free; some roads lead you to places you thought you’d never be, like this place. There’s one road out of this place and it’s the road I cannot take. Instead, all I can do is open up the map in my head, run my finger backward from this place to the place before and the place before that, and think about the roads that got me here.

7:00 a.m.

I blew off my mom’s request that I wear a coat, so I stood on the curb in the cold waiting for the bus wrapped only in my black hoodie. I hated taking the bus, and couldn’t wait until I turned sixteen when ex-Dad promised he’d buy me a car to drive to school. School’s too far to walk to, and I’d rather die than have Mom haul my sorry ass, so I waited, alone. Sure, there was Whitney a few feet away, but she might as well be a thousand miles away. She was bundled up in a long brown winter coat with a bright yellow scarf and matching gloves and hat. When Whitney spoke in math class yesterday, I tried not to look at her. I tried to catch myself, thinking, Stop staring, but wanting Whitney—or most other girls—was like a wildfire, always changing directions.

Whitney stood with fellow preps Erin, Meghan, and Shelby, each one more beautiful and unreachable than the next. They laughed, baring their perfect white teeth to the gray fall sky. Their laughter was a cold hard rain falling down on me: it chilled, reduced, and angered me. I wanted to say to Whitney, I’m not really a bad guy. I’m not smart enough or rich enough or good-looking enough for you, but I’d love only you. I even took a step toward Whitney, but fear pushed me back. There’s a brick wall of frustration firmly placed between the Whitney World and me. I felt like a doomed character in a Poe story: walled in, brick by brick; buried alive.

I never wanted to be a prep like Whitney or Kyle, nor a jock like Rusty Larson or Bob Fredericks, who strolled in all their three-letter cockiness toward the bus stop. Both of them jock jerk juniors who shouted at each other like they were on the football field. They yelled about nothing, other than to prove that this flat land was their mountain.

I clicked on my knockoff iPod (my jPod I call it) and felt the volume vibrating in my ears as I stared with silent rage at my fellow Swartz Creek Dragons. Music saved me and got me through that hate. Morning, noon, night, or whenever the Whitney World tempted me with unattainable beauty and the Rusty Bobs of school showed their colors of confidence, old Zeppelin, in particular “Stairway to Heaven,” let me feel close to human. All the rage in my head and heart vanished into the volume of Plant’s singing, Page’s guitar, and the Jones-Bonham rhythm attack. I didn’t need new music; the best music had already been recorded.

I blew on my ungloved hands; a cloud of white enveloped my paws. The cold didn’t bother me as much as the wind crashing into my face, making my too-pink cheeks turn almost bloodred. When I stared at Whitney’s bright, shiny smile and stylish new shoes, I felt more than ever like I no longer belonged in this neighborhood. In the divorce, Mom got the house, but little else. Ex-Dad left us surrounded by a nice life we see and seek every day, but can never again own.

I gazed down at my watch; some fancy model ex-Dad got me for my fifteenth birthday a few months ago. It was time to make a daily bet with myself on what would arrive first: the yellow school bus or the long-brown-haired mountain known as Brody Warren. I saw the bus up the street just as Brody rounded the corner, running on all pistons. I wondered if he was late because he wanted to be noticed making an entrance or to avoid ex-teammates Rusty and Bob.

“Dude,” I said as I clicked off the music and came alive for the first time that morning.

Brody slapped me on the back. Ash from his cigarette sparked against the gray morning sky. “How you feelin’, Mr. 151?” Brody asked as he offered me the smoke.

“Okay.” I waved off the cigarette, but Brody pushed it toward me.

“Better than ATM Aaron I bet,” Brody said with a grin. Like me, Brody was without a coat, any sense of fashion, or access to a hairbrush. His long brown mane surrounded his face, which was—unlike mine—sprouting a short jungle of whiskers.

“No doubt,” I told Brody, but my thoughts were with Aaron. We called him “ATM” because he’d loaned us money for the past three years. I wondered if last night we should’ve said, Aaron, what’s with you? Why are you drinking so much? Loan us some rum instead of cash.

“Take it, dude,” Brody insisted, and I took the cig. The smoke tickled my mouth going in and burned my nose coming out. I finished it, then threw the butt to the pavement. Brody’s heavy boot ground it into the gray asphalt like an ant that pissed him off. “You were so wasted last night,” he said in his volume-turned-up-to-ten voice.

“I guess,” I replied, almost in a whisper. The Whitneys of the world already thought I was a loser. They don’t need to know they’re right. Everybody already knew about Brody.

“Wasted!” Brody yelled to Rusty and Bob, who gathered up their backpacks adorned with the bloodred Swartz Creek Dragon logo. They were like twins and part of a family of forty brothers, all of them alike in their game day pressed khaki pants and Red Dragon jerseys. They sported football-season short hair and a complex look of pity, sadness, and disgust as they glared over at the fallen angel Brody. Their lips never moved but their eyes taunted, then rejected, Brody’s existence. “Assholes,” Brody mumbled as we fell last in line for the bus.

Nobody spoke when the bus pulled to the curb, a plume of exhaust briefly covering us all. Like lost explorers walking out of a jungle mist, we boarded the bus and took our unassigned but very much carved-in-stone seats. The Whitney World rode in the middle, while the Dragon True Believers sat up front like gatekeepers. We sank like stones in the back of the bus.

“Wasted,” Brody hissed at Rusty and Bob when he passed by them. Big though they were, the jocks balled their fists but never moved their muscles against Brody, their ex-teammate. Brody was a varsity starter as a freshman; an all-state sure bet at training camp two months ago; a kicked-off-the-team loser who stood before them that football-Friday morning.

“Dude, let’s go.” But as soon as the words left my lips, I knew instead I should’ve said, Dude, let it go. I knew that was advice I should’ve given myself about so many things.

“Whatever, Pool Boy,” Brody cracked, but I didn’t laugh. I like Brody’s 151 nickname for me better. This was a p

ut-down name: I’m a terrible pool player, while Brody ruled the green felt. The pre-rum-filled run of the table the night before at Space Invaders arcade was the usual with Brody winning six games to my zero. Aaron won against me, lost against Brody, but didn’t care either way. Brody’s more athletic than me, while Aaron’s hand-eye coordination is honed with hours of Xbox expertise. I suffered the humiliation as the price of friendship admission.

Our seat in the back was near the stoners like Dave Wilson. Dave’s sleeping face was pressed against the window. If it were ten degrees colder, his drool would’ve frozen on his chin.

“What time?” Brody asked as he pushed himself into the seat and tossed his backpack onto my lap. It didn’t hurt since the nearly empty pack weighed so little. I took a few college prep courses, but Brody’s college future vanished with his football banishment. He’d given up even caring about school.

I was puzzled by the question: what time for what? What time was it? What time would we get together later that night? I was still thinking when Brody grabbed my wrist.

“Nice watch.” Brody grunted, then kicked the seat in front of him. “Your dad, right?”

“Yeah, ex-Dad,” I corrected him as his eyes closed. I should’ve said, Brody, your dad left your life because of an accident on the road. My dad’s exit was no accident; it was because of the road I decided to take.

While Brody slept, I put the headphones back on, then clicked on the jPod to drown out the noise surrounding me. I was lost in crashing music and imaginary conversations as the bus made one of its last stops. The stop was in front of the WindGate trailer park, where Roxanne Gray slithered on board. She wore a denim jacket with a white skull patch, a tan wool cap that pushed her brown hair out like the top of a chocolate muffin, and her usual crooked half smile. I ignored her that morning like I had done most every day for years; like I wished I’d done weeks ago at Rex’s end-of-summer, life-ruining party. I wanted to ask her, Roxanne, why did you choose me to fool around with? Why didn’t you pick somebody else? Instead, I listened to Zeppelin and stayed mute until the jolt of the bus stopping woke up Brody.

Head Kick (The Dojo)

Head Kick (The Dojo) Duty or Desire

Duty or Desire Returning to Normal (Locked Out)

Returning to Normal (Locked Out) Things Change

Things Change Controlled

Controlled Friend or Foe

Friend or Foe Stolen Car

Stolen Car Heart or Mind

Heart or Mind The Franchise

The Franchise Triangle Choke (The Dojo)

Triangle Choke (The Dojo) #1 Out of the Tunnel

#1 Out of the Tunnel Chasing Tail Lights

Chasing Tail Lights Nailed

Nailed Combat Zone

Combat Zone Outburst

Outburst Barrier

Barrier Fight or Flee

Fight or Flee Doing Right (Locked Out)

Doing Right (Locked Out) Cheated

Cheated Guarding Secrets (Locked Out)

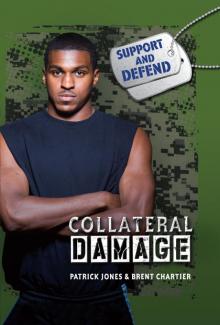

Guarding Secrets (Locked Out) Collateral Damage

Collateral Damage On Guard

On Guard Always Faithful

Always Faithful The Gamble (Bareknuckle)

The Gamble (Bareknuckle) Side Control (The Dojo)

Side Control (The Dojo) Bridge

Bridge Body Shot (The Dojo)

Body Shot (The Dojo) The Tear Collector

The Tear Collector Slammed

Slammed Drift

Drift Pass It Forward

Pass It Forward Target

Target Freedom Flight

Freedom Flight Taking Sides (Locked Out)

Taking Sides (Locked Out)