- Home

- Patrick Jones

Doing Right (Locked Out)

Doing Right (Locked Out) Read online

Text copyright © 2015 by Patrick Jones

All rights reserved. International copyright secured. No part of this book may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means—electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwise—without the prior written permission of Lerner Publishing Group, Inc., except for the inclusion of brief quotations in an acknowledged review.

Darby Creek

A division of Lerner Publishing Group, Inc.

241 First Avenue North

Minneapolis, MN 55401 USA

For reading levels and more information, look up this title at www.lernerbooks.com.

The images in this book are used with the permission of: © Photodisc/Getty Images (brother and sister); © iStockphoto.com/DaydreamsGirl (stone); © Maxriesgo/Dreamstime.com (prison wall) © Clearviewstock/Dreamstime.com, (prison cell).

Main body text set in Janson Text LT Std 12/17.5.

Typeface provided by Adobe Systems.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Jones, Patrick, 1961–

Doing right / by Patrick Jones.

pages cm. — (Locked out)

Summary: Puzzling over conflicting advice from family members, seventeen-year-old DeQuin Lewis continually faces trouble in his St. Paul, Minnesota, neighborhood, until a betrayal leads him to fresh start in an alternative school, one confrontation away from losing everything.

ISBN 978–1–4677–5803–1 (lib. bdg. : alk. paper)

ISBN 978–1–4677–6187–1 (eBook)

[1. Conduct of life—Fiction. 2. African Americans—Fiction. 3. Prisoners’ families—Fiction. 4. Fathers and sons—Fiction. 5. Uncles—Fiction. 6. Grandfathers—Fiction. 7. Saint Paul (Minn.)—Fiction.] I. Title.

PZ7.J7242Doi 2015

[Fic]—dc23

2014018197

Manufactured in the United States of America

1 – SB – 12/31/14

eISBN: 978-1-4677-6187-1 (pdf)

eISBN: 978-1-4677-7689-9 (ePub)

eISBN: 978-1-4677-7690-5 (mobi)

To Raven

—P.J.

PART ONE: SEPTEMBER

1

“You have a collect call from Oak Park Heights, will you accept the charges?” The operator’s tone is flat, cold.

“Yes,” I say.

“DeQuin, how you doin’?” Dad asks a few seconds later. There’s noise behind him. Other voices. Prison’s not a place where you go to get privacy, unless you’re in solitary.

“A’right,” I answer. And then there’s that familiar pause of two people who have no idea what to say to each other, even though they’re related.

“What you up to?” Dad asks.

“Not much. The usual.”

I’m always at a loss for what to say when Dad calls. If I talk about working at KFC, Dad resents it because it reminds him that his brother—my uncle Lee—is a success, while he’s a prisoner. Lee’s the general manager for a string of KFCs around St. Paul. I’ve been working at one of ’em for almost two years. With school starting this Monday, I’ll cut to twenty hours a week instead of the forty I did all summer. Still, I’ll be putting a good chunk of money in the bank for college.

If I talk about school, Dad resents that too, since he’d already dropped out before tenth grade. I’d talk about a girlfriend, except I don’t have one at the moment. Dad’s always game to discuss females. He was a player back in the day, which is probably why my mom left. She’s something else we don’t talk about.

“Me and Martel and Anton are ’bout to head to Valleyfair,” I say. Just to be saying something. And also so that Dad will know my friends are waiting on me. They’re in the kitchen right now, putting up with Gramps and his stories.

In fact, I can hear Gramps from the other room: “Why you boys dressed like that? Pants hanging down like that. Show some respect for yourselves...”

“Good, good,” says Dad. He’s heard all about Martel and Anton, even though he’s never met ’em. The three of us have been cruising around together since we were in kindergarten, ’bout the same time Dad started his life sentence. Usually, when I can’t think of much to talk to Dad about, I’ll talk about Martel and Anton. Not this time, though. Lately I’m getting the sense that Martel and Anton only care about living day to day, and if I hang with them much longer, I’ll be retracing Dad’s footsteps.

So...more silence. Like those gray walls that stand between Dad and me have somehow made their way into the phone lines.

“When you coming to visit?” He makes his questions sound like orders.

“Soon.” Whenever Uncle Lee decides to take me. Usually it’s every few months, but Lee’s been working a lot lately, hasn’t had much time off. And since I’m still only seventeen, I can’t go on my own. Even if I wanted to. Which I’m not sure I do.

I hate these calls. They’re just reminders that Dad and I barely know each other. And that’s another thing I can’t talk to him about: the reason we’re strangers.

It’s not just because he killed a guy in some messed-up gang stuff. He could’ve done less time, he said, if he snitched on his squad, but “real men protect their own.” So he saved guys who wore the same colors from doing time, and he left his five-year-old son without a father.

“Well—my time’s ’bout up, DeQuin. You take care.”

“OK,” I say. “You too.”

It’s how we always end these calls. It fits. Dad never took care of me, but he expects me to take care of myself.

Anyway, I’m glad the call’s over. Unlike Dad, I’ve got places to be.

2

“He pulled out a gun!” Gramps yells as I walk into the kitchen. Martel and Anton have been stuck at the table with Gramps while I was talking to Dad.

“Was it a choppa?” Martel asks Gramps, who gives him a blank look. I see that look a lot.

Martel sighs, tries again. “What kind of gun was it?”

“A shotgun if I recollect, but that’s not important,” Gramps continues. “What’s important is you boys knowing what happened that day in Selma.”

“Can we bounce?” I ask Gramps. I’ve heard this story a hundred times: Gramps walking across some bridge in Alabama back in the sixties, part of some big civil rights march, and getting the crap beat out of him by the police. I could tell it in my sleep.

I slip in my ear buds and head for the door. But Gramps gives me that stern, cop-like “freeze” glare, so I pause.

“Mr. Jimmie Lee Jackson was a deacon at my church in Marion, Alabama,” Gramps says. “And they shot him dead in 1965 for trying to vote.”

“And that led to the Selma protest march and you seeing Dr. King.” I try to move the story along. “And that’s why Dad’s name is Jimmie and why Uncle Lee’s name is Lee.”

Gramps isn’t pleased at my interruption. “You should listen more, talk less, DeQuin.”

It’s been like this all summer, ever since Gramps got sick and moved up from Alabama to live with Uncle Lee and me. Nothing but complaining about everything. Mostly about me.

“And you should take those things out of your ears when I’m talking to you.” He points at my buds like they’re illegal. “I don’t understand why you all have to always be listening to that music. Glorifying guns and criminals. Using that word. Disrespecting black women...”

I cut him off. “Wait a second. You said ‘you all listen to.’ What do you mean by that?”

“You know what I mean,” Gramps says. “You young people.”

I could argue with him. We argue a lot, Gramps and me. He’s got it in his head that everyone my age is looking for trouble. I guess Martel and Anton won’t do much to change his mind. Like Dad, they’re eas

ing into the fast flow of the streets.

And me?

I don’t know.

Uncle Lee’s always telling me that with my good grades, I could get into college easy—even get a scholarship to help pay for it. He sees me getting some fancy business degree, following in his footsteps instead of in Dad’s.

I’m not sure I want a life like Lee’s. He’s always working, always stressed. Always trying not to get on his boss’s bad side or make a mistake that could get him in trouble.

But I know I don’t want a life like Dad’s.

And I know I don’t have time to get into it with Gramps right now. “OK, we’re out,” I say. “Those roller coasters don’t run all night.”

“Shouldn’t you two be working?” Gramps asks Martel and Anton. “Don’t you boys have jobs like DeQuin?”

They work, but not at jobs they’d tell him about. “Yeah, fry me some chicken, DeQuin,” Anton says.

“With a side of taters,” Martel adds. They laugh loud and long like they’re high already.

“That chicken is going to pay for DeQuin’s college,” Gramps says. “Hard work turns that fried chicken right into tuition. I worked in the steel mills to pay for my son Lee’s college, no shame in working to pay your way...”

“Let’s goooo,” I say and motion for Martel and Anton to join me. Martel gets out the keys to his ride, a three-year-old Jeep that’s way nicer than my ancient Corolla.

“One more thing, DeQuin,” says Gramps.

“Yeah?”

He pounds his cane hard on the kitchen floor. “Pull up your dang pants!” We laugh, since he says it all the time. Sagging, so they say, started in prisons and spread to the outs. I don’t know if that’s true. I’ll have to ask Dad.

3

“She’s fine, go talk to her!” Martel pokes me in the side. We stand together outside the Demon Drop ride at the amusement park. On the last Saturday night of summer vacation, it’s packed, mostly with people our age, but not so much our color.

“Let it go,” I say, trying not to look at the cute white girl a few feet away. She stands with two friends, also white. They pass a phone around, laughing loud.

“Three of us, three of them. Do the math, Einstein.” Anton adds his poke in my side. They’re always calling me Einstein. I get good grades at school, even made honor roll last year as a sophomore, so they’re always ragging on me.

“Then you talk to ’em, Anton,” I snap back.

“Raquel would kill me!” I let that go. I know he’s cheated on her before, not that it’s any of my business. Me, I don’t go that route. I prefer one girl at a time.

“But that doesn’t mean we can’t party with ’em,” Anton adds. “Come on, it’s almost midnight, they’re about to close up. It’s now or never.”

“DeQuin, don’t be a coward,” says Martel. “Run up there. We know you like the ladies, and ladies like you plenty.”

“You crazy, Martel.” But it’s the truth. While I don’t have a girlfriend right now, that’s normally not the case. I guess being tall and “fine,” as the girls always say, tends to work out well for me.

“How many times you hooked up with a white girl?” Martel asks.

“That don’t matter none.”

“Then help a brother out,” Martel says, and then pushes me hard toward the three girls.

“My cuz thinks you’re fine,” I tell the shortest of the girls, since Martel is only 5’5. He seems even shorter because he hangs with two six-footers. “What’s your name?”

The short girl doesn’t look pleased. The tallest one says, “Her name is Brittney.”

I laugh. Seems every third white girl who ever works at KFC is named Brittney. Brittney whispers for her friend to shut up. I point back at my boys. “That’s Martel.”

“What’s your name?” the tall one asks, ignoring her friend’s glare.

“DeQuin Lewis, Harding High School, St. Paul, Minnesota,” I answer. “And where are you all from?” I notice Brittney wears an oversize varsity jacket from Woodbury, better known with us as Whitebury. Before the tall girl can answer, the third girl tugs on her arm.

“Chelsea, let’s go,” third girl whispers.

“Chelsea and Brittney and whoever, nice to meet you,” I say. “If you three want to—”

“We have to go,” third girl says, aiming her words at me, not her friends. Behind me, I hear Martel and Anton laughing like little kids on Christmas morning.

“Hit me up online,” I say to Chelsea, she of the long brown hair and ice-blue eyes. “Tell your friends not to worry. I’m a’right. I don’t bite—that is, unless you want me to.”

Chelsea rolls her pretty blue eyes, laughs, and starts to walk away.

“Hey, what’s up?”

Three big white guys come up behind the girls. They all have shaved short hair like football players wear during the season. Two of them have on varsity jackets loaded with letters. All three are cupping super-sized sodas in their paws.

“These guys bothering you, Brit?” asks the tallest guy, the one without a varsity jacket. Tiny Brittney glances at him, then back at me.

“We were just talking,” I say, already backing away. “It’s all good.”

But now Anton and Martel have come closer. Anton marches up to the tall guy and gets right in his face, nose to nose. So close I wonder if the guy’s gonna get a contact high.

“You got some problem with us?” Anton says.

“Anton, let’s just go,” I say. I reach for his arm, but he pulls it away.

“Shut up, Barack!” one of the other guys snaps at me.

“What did you say?” And it’s on. Back and forth, jaw to jaw, each of us bust out our A+ insult game, except I’m way too quick for these fools.

“...And another thing—”

“If you want to fight, Barack”—the guy pushes me in the chest—“let’s fight!”

If I was Grandpa, I’d take his crap. If I was Dad, I’d clean his clock. If I was Lee, I’d just walk away.

He pushes me again.

I break my stare and take a quick look around the amusement park. The odds aren’t fair. A fight won’t end well. From the corner of my eye I see two security guys—one white, one black—running at us. There’s not going to be a fight, but I can still put some fear into these idiots.

“You sure about that?” I raise my shirt so he can see the top of the object tucked in the waistband of my boxers. In the dark, I’m betting that all he can see is a black bulging shape. “You sure you want what I’m packing?”

The big guy slaps his friend’s arm and motions for him to look at me. As soon as they get a glimpse, I put my shirt down. The Woodburys head east, we head west. It’s over.

When the security guards catch up to us, my heart’s booming like a bass riff. “How’s it going, boys?” the white guard asks.

“What’s the problem?” adds the black guard with just as much “I’m in charge” attitude.

In the background, I hear loud screams from the top of the coaster. “What’s your problem?” I shoot back. Martel and Anton look all stunned. Normally I let stuff go. I don’t want to be a hothead like my dad, getting into trouble and going to jail, but something about these guys bothers me. Why they hassling us and not the kids from Whitebury?

“We don’t need any trouble tonight, guys,” the black guard says. “As a matter of—”

The white guard cuts him off. “Why don’t you boys head back home?”

It’s one thing when Gramps calls us boys. This is different.

For a split second I think about taking a step closer to him. Getting up in his face. Saying “Do I look like a boy to you now?”

But I know it’s not a good idea to mess with the wannabe cops. Even Martel and Anton have better sense than that.

I spit on the ground and walk away.

4

Martel and Anton are laughing about the guards as we exit the park and make our way to Martel’s Jeep.

“Did

you see the look—” is as far as Anton gets before we see the three guys from Woodbury standing in the emptying parking lot.

“Keep walking,” I say.

“No, let’s do this,” Martel says. “They’re big, but I messed up bigger dudes than them.”

“Martel, ain’t worth it,” I say, trying to keep my voice calm even when inside I’m feeling anything but. “School starts Monday. I don’t want to spend a night in jail.”

“It ain’t so bad,” Martel says. Both he and Anton got arrested for distribution, but after a few nights in juvie, they got put on ankle bracelet. Martel talks about spending time at JDC like it’s something to be proud of, which I don’t get. Maybe if he’d spent his childhood looking at his dad through a glass partition, he’d feel different.

“It’ll be worse for them,” Anton says. “They’ll spend the night in a hospital.”

I trail behind, not sure what to do. Unlike them or Dad, I’ve never been in a serious fight. My smart mouth got me close a few times, but I normally bluff my way out of it like I did in the park. I don’t think that’s going to work again. If my friends fight, then do I follow?

“You with us, DeQuin?” Martel asks with attitude in his voice like I got no choice. A few months ago, there was no need to ask. But it’s hard to follow someone when you know you’re headed in different directions. I say nothing. They’re running on something almost primal. They got challenged, and everything in their experience tells them to fight back.

“I don’t have—” Martel says right before he gets tackled by two white guys in varsity jackets. Anton gets decked from the side too. The three guys from earlier are still in front of us. Turns out they got backup.

As Martel and Anton fight off the guys who jumped them, the three original guys run toward me.

And I run away faster than whoever runs the hundred-meter on the Harding track team.

I zigzag through the parking lot. The headlights cast shadows around me. The three guys call me a coward and few other names, but they give up the chase pretty quick.

Head Kick (The Dojo)

Head Kick (The Dojo) Duty or Desire

Duty or Desire Returning to Normal (Locked Out)

Returning to Normal (Locked Out) Things Change

Things Change Controlled

Controlled Friend or Foe

Friend or Foe Stolen Car

Stolen Car Heart or Mind

Heart or Mind The Franchise

The Franchise Triangle Choke (The Dojo)

Triangle Choke (The Dojo) #1 Out of the Tunnel

#1 Out of the Tunnel Chasing Tail Lights

Chasing Tail Lights Nailed

Nailed Combat Zone

Combat Zone Outburst

Outburst Barrier

Barrier Fight or Flee

Fight or Flee Doing Right (Locked Out)

Doing Right (Locked Out) Cheated

Cheated Guarding Secrets (Locked Out)

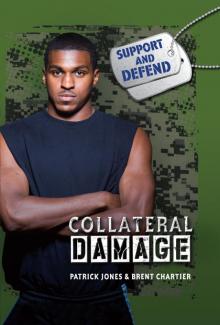

Guarding Secrets (Locked Out) Collateral Damage

Collateral Damage On Guard

On Guard Always Faithful

Always Faithful The Gamble (Bareknuckle)

The Gamble (Bareknuckle) Side Control (The Dojo)

Side Control (The Dojo) Bridge

Bridge Body Shot (The Dojo)

Body Shot (The Dojo) The Tear Collector

The Tear Collector Slammed

Slammed Drift

Drift Pass It Forward

Pass It Forward Target

Target Freedom Flight

Freedom Flight Taking Sides (Locked Out)

Taking Sides (Locked Out)