- Home

- Patrick Jones

Heart or Mind Page 4

Heart or Mind Read online

Page 4

“It can’t be that bad inside, can it?”

“I didn’t finish,” Rodney says. “I’d rather die than be separated from you.”

15

RODNEY

“That’s what happened, honest, Larry.” Rodney’s at his uncle’s door. Jawahir stands behind him, clutching onto his left arm. “It was pure self-defense, you ask anyone who was there—”

“The brothers will say that, but you think the Somali kids will say the same thing?” Larry asks. He looks apologetic like he knows he probably offended Jawahir.

“Maybe so, but I—we—need a place to hide, just one night.”

Uncle Larry’s got the door partially open, but the chain is still on. “Then what?”

Rodney pulls Jawahir closer. “Then we’re running away together.”

“Where you running to, Poe?”

Rodney turns toward Jawahir, bends down to kiss her, and then returns his attention back to his uncle. “I don’t know yet, but someplace where there isn’t all this hate.”

Larry shakes his head like he’s stunned at the words from Rodney’s mouth. “You want to act like a man, yet you talk like some kid. There isn’t any place in the world like that, Poe.”

Rodney looks away from his uncle. “Maybe not, but until we figure it out, can we—”

“Just a second.” Larry undoes the chain and opens the door. “Just you, Poe.”

Rodney kisses Jawahir. “I’ll be right back,” he says before stepping in the doorway. He takes six steps inside. His uncle wears his blue uniform from his job driving a shuttle back and forth over the same roads every day. Rodney wonders if a job like that isn’t much different than prison or his time at CHS. Nothing but doing the same things someone tells you to do over and over as you count minutes, hours, and days until it’s done. His uncle even wears an ugly blue shirt like Rodney did at CHS.

“Listen, one night, but that’s it,” Larry says. “I’m not on parole anymore, but I don’t need any light on me harboring you. If you get caught, I don’t know anything. You didn’t see me.”

Rodney nods. “She’s staying with me. Do you think you could—”

His uncle finishes his sentence with a smile. “Find another place to be? No problem, but don’t be getting busy on my bed. The couch is foldout, and there are some sheets in the bathroom closet.”

“I didn’t really plan, so . . .” Rodney averts his eyes, embarrassed.

Larry roars in laughter and slaps his nephew’s back. “Top drawer of the dresser by the bed.”

16

JAWAHIR

“Is the sun really rising already?” Jawahir sighs sadly. She rises from the sofa bed, the thin sheet wrapped around her bare shoulders. “I don’t want our night to end.”

Rodney pulls her gently back next to him. “Who says it has to?”

Jawahir strokes the side of Rodney’s unshaven face. “What are we going to do?”

“You have any relatives we could—” Rodney starts.

“No, most of them live here in Minnesota, but I’m sure those who don’t wouldn’t allow me to live with them. If so, it would only be to trick me until they could send me back to my father.”

“I got a cousin in Chicago, one of Larry’s sons. Maybe—”

“My father would find us,” Jawahir whispers. “He would spare no expense. I’m sure right now he has all of his and Farhan’s father’s friends out looking for me as if I were some criminal.”

“You’re not a criminal, nor am I,” Rodney reassures. Jawahir kisses him. “I was, but I’m not now.”

“I don’t care about anything before we met. All I care about is since you helped me that—”

Rodney laughs. He points at her dress and his shirt on the floor. Both stained with blood from the fight. “It seems like we’re trapped in some sort of circle.”

Jawahir pulls closer. “Life is a circle. I’m just glad we’re traveling around it together.”

Rodney takes a deep breath and reaches for his phone. He scrolls through his messages, but stops suddenly. “I’ve got a bunch of calls from my PO. I gotta get out of town. Jump on the bus, and quick.”

“I’ll come with you.”

“No, not now. You go back home and tell everyone it’s over between us. Renounce me, do whatever you have to do so you don’t get punished or hurt. Save yourself. Then once I got things squared in Chicago, I’ll send for you, through Larry, and we’ll leave all this behind.”

“I don’t think I can—” Jawahir starts, but Rodney silences her with a kiss.

“We went too many years without knowing each other. We can make it a few more—”

“Days, not weeks.” She senses a day without Rodney will feel like the longest week of the year.

17

RODNEY

“I promise, days, not weeks.” Rodney leans out of bed and reaches for his pants. He pulls a roll of bills from his pants pocket.

“Look, buy a disposable phone.” Rodney hands Jawahir money. “Hide it from everyone, but use it to call me. I’ll go crazy not hearing your voice.”

“Sit backward on the bus, so it seems real.”

Rodney laughs. He’s starting to speak when his phone rings. It’s Larry. He picks up. “Uncle Larry, I need to get a hold of Drayton in Chicago. I lost his number. Can you hook me up?”

“Why? You thinking of staying with him?” Larry asks over a noisy background.

“Just until I can get things sorted out,” Rodney says.

“It’s best. I mean, it is all over the news. They got the mayor, the police, a whole bunch of preachers and whatever, appealing for peace. They closed your school for the day. Crazy, man.”

“They say anything more about me or how Marquese is doing?”

“No, just that a lot of people are still in the hospital, and they’re looking for you,” Larry says. “Even showed your photo. Don’t worry. It’s one from your yearbook, not some ugly mug shot.”

“I’m not turning myself in. I didn’t do anything wrong, but nobody is going to listen.”

“They can’t listen because there’s too much noise,” Larry says. “People only hear what they want to hear, that’s the whole problem. People got to walk around in somebody else’s shoes.”

“I know. I didn’t used to get that, but I learned that at CHS. Empathy. But people judge.”

“That’s the truth, and sooner or later you’re gonna face it, but I understand you needing to get out of town, getting some time and distance. That’s the best strategy. You need money or anything?”

Rodney puts the phone against his bare chest. “He wants to know if we need anything?” he asks Jawahir. She drops the sheet from her bare shoulders, and Rodney smiles wide. “Yeah, another hour here.”

18

JAWAHIR

“Get in the van!” Jawahir’s father shouts at her. Shouting has been his normal tone since she returned home this morning. “You’re going to the hospital to visit Farhan. You will visit him every day until—”

“Father, I am sorry about everything,” Jawahir says, cutting her dad off. Even though she did exactly as Rodney suggested—denounced him and vowed never even to speak his name again—her father is not satisfied. She might as well be speechless for he refuses to listen to anything she says.

“I don’t believe you,” he counters as she climbs in. Ayaan follows behind. The front seat remains empty since her mother is working, and it’s like her father doesn’t want to be that close to Jawahir, like she caught a disease or something. “I believe your actions have brought shame on your family and on your community. I want to hear nothing more, understood?”

“Yes, Father,” Jawahir whispers. The ride to the hospital is mostly silent, as if her father is too angry, feels too betrayed, to talk with anyone. I know betrayal, too, Jawahir thinks as she glares at Ayaan, sitting next to her. Ayaan, who obviously betrayed her and set all of these horrible actions in motion.

At the hospital, her father drops them by the

front door and goes to park the van. “I know what room he is in,” Ayaan boasts, like she knows the answer to some test. Ayaan, with longer legs and greater eagerness to see Farhan, races ahead. Jawahir catches up just as the elevator door is closing. Rather than pushing a floor, Ayaan holds the door close button.

“I don’t believe you either.” Her voice is cutting, like a scalpel or Farhan’s switchblade.

“I’m telling the truth,” Jawahir lies. She starts to repeat her story about how wrong she was to take up with Rodney. How she knows now that everyone else was right and she was wrong. As she says the words, she tries to make them real, but Ayaan knows her too well.

“Where is he?” Ayaan demands.

“I don’t know.”

“He’s dead.”

Jawahir tries to keep her hands steady. “How could you say that?”

“That’s what you’d better believe, Jawahir, because he’s never coming back to you.” Jawahir starts to cry. “And you blew your chance with Farhan after what that thug did to him.”

“Rodney’s not a thug.”

Ayaan pushes herself toward Jawahir. “You tell us you want nothing to do with it and it was all a mistake, yet you still defend him. He took from you the ability to tell the truth. You didn’t come home last night, so I have to wonder what else he took from you.”

Jawahir thinks about slapping Ayaan, but holds back. She feels no shame, no regret for what happened last night with Rodney. Her love is bigger than her faith.

Ayaan lets go of the button and the elevator begins to rise. As they pass by each floor, Ayaan continues to bad-mouth not just Rodney, but all the African American kids at Northeast. “Rodney belongs behind bars. They should never have let him out.”

Ayaan steps of the elevator, but Jawahir doesn’t move. When she reaches to press the close button, Ayaan yanks her from the elevator, then down the hall. She lets go as they enter Farhan’s room. Jawahir feels like fainting from the sight of Farhan’s face covered with bandages and the tubes in his arms.

Farhan motions for just Jawahir to come closer. She stands next to the bed. “I’m sorry about all of this, Farhan. This has gone too far. You’ve got to stop. Mercy. Peace.”

Farhan takes Jawahir’s hand and pulls her closer. “I’m sorry about your dress.”

Jawahir’s shaken. That is what you’re sorry about? she thinks. My dress, not stabbing someone?

“When I get out of here, I will buy you a new one,” Farhan speaks through clenched teeth, his jaw probably broken during the fight. “In fact, I’ll buy you two new dresses, Jawahir. A white one for you to wear to our wedding. And a black one for you to wear to Rodney’s funeral.”

19

RODNEY

“There are three things worth killing for,” Marquese tells Rodney. Rodney rides in the big blue MegaBus on the way to Chicago; Marquese is still in the big white hospital on the way to recovery. “I guess you don’t think about something like that until something like this.”

Rodney tries apologizing again, but Marquese isn’t having it. “It’s worth dying for your family, and your family is all your brothers, and that includes you. It’s worth dying for your country, and . . .”

Rodney tries to hear over his rumbling stomach. The money he gave Jawahir for a phone and the one-way ticket to Chicago was almost all the money he had. “So what’s the third, Marquese?”

“Your woman. I didn’t get that because you know I ain’t never had nothing like you and Jawahir. Man, I can see it between you. You two are like cartoon magnets with wiggly lines drawing you to each other. I think that’s why I stood up. Farhan wasn’t just insulting me, you, and all brothers. He was insulting love, and that’s just wrong. When I’m dead and gone, all that money I made ain’t gonna remember me. It ain’t gonna cry; it’s just going into somebody else’s pocket. But you, you got it.”

“Had it.” Rodney tells Marquese about going to Chicago and being away from Jawahir. “I could come in the hospital with you and they could cut out a piece of me, and it won’t hurt more than this.”

“Then why you running?”

“If I stay, I’m going to get violated,” Rodney confesses. “I can’t go back inside.”

“You afraid Jawahir would pull an Aaliyah and drop you when you’re—”

“No, that’s not it.” Of this, Rodney is more than one hundred percent sure. “But I said I wasn’t going back in. I told everybody at CHS, everybody at home, and everybody at school that I was done with that life. But mostly, I told myself that I’d never step foot inside again and I’m going to keep my word.”

“I’ll testify that you were trying to break up the fight.” Rodney flashes not on the images of the fight, but the sound of the knife entering Marquese’s body and then his body hitting the ground. “I’ll tell—”

“And we know how much judges and POs believe what young black men say,” Rodney says, feeling his anger rise. “Farhan and his buddies got way more cred than any of us and you know that.”

Marquese, who loves to argue, doesn’t say a word. Both he and Rodney know the system. “So how you feeling?” Rodney asks. “When you going home and going back to school?”

Marquese laughs, then starts coughing. When he starts talking again, his tone is different, like he’s in pain. “I don’t think school will take me back. I think they want me gone, and you too I bet.”

“Probably, that’s what they do.” Rodney remembers Principal Evans trying to get him to enroll in River Creek Academy, one of the charter schools the district uses to warehouse problem kids and ex-cons. But since he wanted to play football, or thought he did, he got Bryant to get Coach to convince Evans to let him back in. He’s got no ally in his corner now, and more enemies than he’s ever had.

Marquese and Rodney keep talking; it makes the miles so much quicker, and Rodney can only assume it makes hours laying in hospital bed a little less painful by talking to a friend.

Rodney finally ends the call when another comes in: Jawahir. “It’s her, Marquese, I gotta go.”

“Family, country, and love,” Marquese says. “Worth killing for, worth dying for.”

Rodney smiles at the idea of big bad Marquese falling in love.

He quits smiling when Jawahir tells him what Farhan said about buying two dresses.

“I’m scared, Rodney,” she says. Rodney hears the terror in her voice. He balls his fists in rage.

“Gimme a couple of days and—”

“It won’t make a difference,” Jawahir says, her voice still shaking. “Nothing will make a difference. We’ll never be together, not in Chicago, not here, maybe not until we get to Jannah.”

“Jannah?” Rodney asks.

“Paradise, or what you might think of as heaven.”

Rodney tries to hold back a laugh, but can’t manage to do so. “I ain’t going to Paradise.”

“How can you say that?”

“Heaven’s for good people, and I’ve only been a good person since I met you.”

Silence makes Rodney think the phone’s cut out, but when he looks at the screen, the call seems to be working. “Jawahir, are you there?”

“Yes, Rodney, yes, I am here. I’ll pray for you, for both of us to go to Paradise.”

“Jawahir, when we’re together again,” Rodney whispers softly as if Jawahir’s ear was next to his, “that’s heaven for me.”

20

JAWAHIR

“You can’t sit here,” ZamZam says sharply as Jawahir tries to sit at the table filled with other ninth-grade Somali girls. Girls she’s known most of her life, girls she thought were her friends. “Nobody wants you at this table. Nobody wants you at this school. Why don’t you and Rodney do all of us a favor and take your disgusting little love affair someplace where we don’t have to watch.”

Jawahir pulls a deep breath into her lungs, shuts her mouth tight, and heads for another table.

With the same response.

And another, and another, and another unti

l she’s exhausted half of the tables occupied by Somali students. She looks quickly over at the tables occupied by the African American students. The one closest contains the girls who were about to jump her when she was down, if not for Rodney.

Humiliated, she turns and dumps her lunch into the garbage. Trying not to cry, she walks head down out of the cafeteria, but once she’s outside, she breaks into a run.

As she’s running down the hallway, she hears a voice yell her name over and over. She collects herself, turns, and sees Principal Evans standing, looking very much pissed off. “Jawahir, in my office, now.” Evans motions for Jawahir to follow her like she was a scared pet dog.

Jawahir’s stomach clenches with fear; she’s never been in a principal’s office. Never been in trouble, never been anything but an A student and obedient child with lots of friends. Now she’s lost all of those things, and the reason she lost them—Rodney—isn’t anywhere close.

“You can’t run in the hallways,” Evans scolds after Jawahir steps inside the doorway.

Jawahir nods but thinks it’s odd Evans called her in to say that. What am I doing here? she thinks.

“Now, Jawahir, as you know we’ve had a few little issues recently between different groups of students.” Despite feeling terrible, Jawahir feels like laughing at Evans describing brawls, a stabbing, and multiple arrests as “a few little issues.” Evans continues, “I brought together a small group with some outside help, but basically, that doesn’t seem to be working. So what I’m thinking, and I think Coach Martin might agree with me: go big, go long.”

Jawahir nods but says nothing. All she knows about football is that Martin coaches it.

“I understand that you and Rodney Marshall have become quite close, actually. A couple, I understand, is that correct?”

Jawahir shakes her head to the negative. “We were, but that’s over.” It hurts her to tell the lie, as if it might jinx their love and that somehow by saying those words it might make them true.

Evans fiddles with items on her desk. “Really? I must have had some incorrect information.”

Head Kick (The Dojo)

Head Kick (The Dojo) Duty or Desire

Duty or Desire Returning to Normal (Locked Out)

Returning to Normal (Locked Out) Things Change

Things Change Controlled

Controlled Friend or Foe

Friend or Foe Stolen Car

Stolen Car Heart or Mind

Heart or Mind The Franchise

The Franchise Triangle Choke (The Dojo)

Triangle Choke (The Dojo) #1 Out of the Tunnel

#1 Out of the Tunnel Chasing Tail Lights

Chasing Tail Lights Nailed

Nailed Combat Zone

Combat Zone Outburst

Outburst Barrier

Barrier Fight or Flee

Fight or Flee Doing Right (Locked Out)

Doing Right (Locked Out) Cheated

Cheated Guarding Secrets (Locked Out)

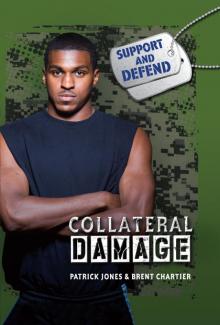

Guarding Secrets (Locked Out) Collateral Damage

Collateral Damage On Guard

On Guard Always Faithful

Always Faithful The Gamble (Bareknuckle)

The Gamble (Bareknuckle) Side Control (The Dojo)

Side Control (The Dojo) Bridge

Bridge Body Shot (The Dojo)

Body Shot (The Dojo) The Tear Collector

The Tear Collector Slammed

Slammed Drift

Drift Pass It Forward

Pass It Forward Target

Target Freedom Flight

Freedom Flight Taking Sides (Locked Out)

Taking Sides (Locked Out)