- Home

- Patrick Jones

Guarding Secrets (Locked Out) Page 4

Guarding Secrets (Locked Out) Read online

Page 4

“Nothing to worry about,” Father Gomez said. “We all have our bad days.”

“So I’m forgiven.”

“Of course.” He smiled, but his expression changed when he saw Camila’s tears. “What’s wrong?”

“Is it that easy? Is it that easy to forgive someone?” Camila asked.

“The Bible tells us that no matter how serious the sin, God is willing to forgive us. But walking out on youth group isn’t a serious sin.”

Camila couldn’t look up.

“Camila,” said Father Gomez softly, “is there something else you want to tell me?”

Camila drew a long, slow breath. “Yes, there is.” Then she told Father Gomez about her mother, her crime, and her approaching execution. She talked so fast, the words fell over each other. Only once before had she told anyone. Back in fifth grade, she told her best friend, Gabriella Diaz. It felt good to tell someone, until they weren’t best friends anymore. They’d gotten into a fight over something Camila no longer remembered. And Gabriella had told. After that, what little trust she had to give, she held inside, afraid to surrender it again. Until Juan, she’d avoided relationships for that very reason.

“Camila, I’m so sorry. I will pray for you and your mother. Has she repented?”

“She says she has.” But Camila wondered if her mom meant it. Gina had lied for so long about so many things, like every time she signed a letter Love. If her mother loved her, she would be there for her, not two hundred miles away, trapped like an animal in a cage, waiting to die.

“But I don’t know if I can forgive her. I love her, but I also hate her for causing all this pain.”

“Forgiveness is the only way to heal that pain, the only way to peace,” Father Gomez said.

“I just feel so all alone in the world,” Camila confessed. While Father Gomez assured her she was not alone, Camila thought of her mother, soon to be strapped in a chair, as alone as a person could be. Maybe God forgives, but the State of California doesn’t.

16

OCTOBER 8 / THURSDAY / EVENING / LINCOLN APARTMENTS

Aunt Rosa stormed into Aunt Maria’s apartment before Camila had even finished opening the door for her.

“I’ve been calling for hours!” Aunt Rosa fumed as she bulldozed her way into the living room. Nice to see you too, Camila didn’t bother to say.

“We didn’t want to answer the phone,” said Aunt Maria, coming out of the kitchen. “The press.”

Camila doubted that was the real reason. She knew firsthand how difficult Rosa could be. Things hadn’t ended well between them, and Camila had avoided her ever since. Or maybe it was Aunt Rosa avoiding her. Either way, Camila was rarely happy to see her.

“You took the train?” Maria asked Rosa as Rosa dumped an overnight bag on the couch.

“Of course I took the train. And you weren’t there to meet me at the station. Because you weren’t answering the phone. I had to—”

“Are you hungry?” Aunt Maria talked over her older sister. “Dinner’s almost ready.”

Five minutes later the three of them were sitting at the table, eating in chilly silence.

“So what did she choose?” Aunt Rosa asked finally. “Lethal injection or electric chair?”

Camila’s food lurched in her stomach. She set her fork down.

“Let’s not talk about that,” said Maria.

“Not talk about it? You think I came out here to not talk about it? To just ignore it?”

“You didn’t have to come,” Camila muttered.

Aunt Rosa glared at her. “Of course I had to come! The family should be together for something like this.”

“Yeah, because you’ve always been so supportive and comforting,” Camila retorted before she could stop herself.

“Don’t talk to me that way, young lady. Show some respect. If you’re not careful you’re going to end up just like—”

“Rosa, don’t start,” Aunt Maria snapped. “Camila’s not going to be like Gina.”

Camila froze. It was the first time she’d ever heard Aunt Maria, or any relative, say those words.

“Anyway, you always talk about Gina like she was a monster,” Aunt Maria went on. “She wasn’t a monster. She was a scared and lost young woman who made a terrible mistake.” Camila noticed that Maria was already talking about Gina in the past tense.

“You’re too forgiving, Maria,” Rosa shot back. “I was there. You were just a kid.”

“Then tell me, Aunt Rosa, why did she do it?” Camila said quietly. “You’re her older sister. You were there for all of it. You tell us.”

Rosa struggled for an answer. “How can I know what was in another person’s heart?”

“Exactly,” said Camila. “We don’t know. We’ll probably never know. So what’s the point of throwing blame around now? What’s the point of building more walls?”

Her aunts both stared at her—one with surprise and suspicion, one with love and maybe even pride.

Camila picked up her fork again and went back to eating her dinner.

17

OCTOBER 9 / FRIDAY / EARLY MORNING / LINCOLN APARTMENTS

Camila hadn’t slept all night. By the time she called Juan on Aunt Maria’s landline, the darkness had started to turn gray.

“Hello?” Juan’s voice on the other end was a heavy mumble.

“Juan, it’s Camila,” she whispered, praying her aunts wouldn’t wake up. “I’m sorry, but I need to ask you a big favor.”

“At four in the morning? What am I, a farmer?”

Camila knew he meant it as a joke, but she didn’t laugh. “I need a ride.”

“Where do you need to go?” Juan asked, now sounding just confused.

She hesitated. “The other day, Juan, you said you loved me,” she said softly. “If that’s true, that means I can trust you, right?”

“Of course, Camila.”

“And that no matter what, you’ll be there for me, right?”

“Yes.”

“Good, then get over here as soon as you can. Gas up the car because it’s a long drive.”

By the time they reached Chowchilla, Camila had told Juan everything she’d told Father Gomez, and more. Not just about her mother, but about herself. The bullying at other schools, the shoplifting, her party days in Riverside, her night in juvenile hall. Everything except the incidents with Steven earlier in the week. All the time she talked, Juan said very little, asking hardly any questions. The more she talked, the more she needed to keep going. With each sentence she felt as if a weight had been lifted from her chest, as if she could finally breathe freely again.

“I’m sorry I didn’t tell you before,” she said at last. “It’s just that trusting someone is—”

“It’s OK, Camila. First of all, I don’t blame you for what your mom did. And as for what you’ve done—that’s your past. It doesn’t have to be your future. I know you don’t want it to be. And I know there’s so much more to you. So much that I love.”

Juan took his right hand off the wheel and reached out for Camila. She wrapped both of her hands around Juan’s hand: hard knuckles, soft skin, her life, his life. “Thank you, Juan.”

They were getting close to the prison now. “What time is the execution?” asked Juan.

“Midnight. In Folsom.”

“Looks like we’re not the only ones who showed up early.”

He was right. Protestors had gathered all along the road. Some carried signs that seemed to celebrate her mom’s approaching execution: Kill the Cop Killer! Others called for an end to the death penalty, like the one held by a girl about Camila’s age—a white girl with long brown hair: Mercy, Not Vengeance. Trucks with logos from LA TV stations lined the side of the road, complete with dish antennas. Camila wanted to scream at them all to go away. This had nothing to do with them or their stupid causes. “Look at all this!” Juan breathed, almost in awe.

Camila didn’t want to look at it. For a while, on the way here, she’d felt so ho

peful. Juan had been so understanding, so accepting. She’d started to believe this could be easy after all. But that simple joy was gone now. Her heart was no calmer than the scene outside: noisy and complicated, filled with anger and hurt. Would that all go away once her mother was dead? Would Camila be able to snatch back that breath of freedom she’d felt during the drive here? Or had her mom gotten death while Camila got life without parole?

18

OCTOBER 9 / FRIDAY / LATE MORNING / CHOWCHILLA

“How can you not let me see her?”

The gray-haired, white-faced warden remained unmoved. He’d been called when Camila, with Juan’s support, refused to leave after being turned away by the gatekeeper guards. “You know the rules, Miss Hernandez. A minor needs to be with a legal guardian.”

Camila pointed over the warden’s shoulder. “My mother is in there!”

“Your mother is not your legal guardian, as I recall,” the warden said. “Even if she was, you also know the visiting hours are Saturdays and Sundays, so—”

“She won’t be alive next Saturday or Sunday!”

The warden gently grabbed Camila’s arm. “I’m sorry, but you need to go.”

“I need to speak with her!” Camila yelled. “I need to say good-bye.”

“You need to leave now. If you don’t—”

Juan stepped forward. He put his hand on Camila’s arm, just above the warden’s hand. “We’re not leaving.”

The warden let go of Camila’s arm as a look of surprise came over his face. Camila guessed he was not a person often defied. “I’m afraid there’s no other option,” he said.

Camila started to speak, her voice thick with tears, but Juan jumped in. “There are TV trucks outside. If you don’t let Camila see her mother, then that’s our next stop. Do you really want the entire world to know that you denied a daughter a chance to say good-bye to her loving mother?”

Camila could’ve kissed him right in front of the warden. Thank you, Juan. Thank you for being here for me. It had been so long since anyone had stood up for her. One of the consequences, maybe, of living most of her life alone.

The warden smirked. Just a tiny uptick of his lips. Easy to miss, if you hadn’t seen it on a million other faces. “Her loving mother is a convicted murderer. And it’s not my job to worry about what the press thinks. Miss Hernandez, I’m sorry, but if you don’t leave now, I’ll need to call the police.”

“I just want to say good-bye and tell her that … ” Camila started.

“You don’t need to call the police,” Juan said. “We’ll leave. Let’s go, Camila.”

Juan wrapped his arms around Camila and turned her toward the exit. About halfway there, she broke free and raced back to the warden. “Call the chaplain.”

“What?” the warden asked.

“Doesn’t she see the chaplain before—”

“That’s not normal procedure … ”

“Call him, please,” said Juan.

The warden said nothing for the longest time. Then: “Wait here, I’ll see if I can I find her.” He turned away, cell phone in hand.

Juan pulled Camila closer. She kissed him, but then her eyes scanned the familiar room. She broke away and went over to pick up a visitor application, along with a short yellow pencil. Sitting at the hard table, she turned the application over and started to write.

Dear Mother,

I came up here to see you, but they wouldn’t let me in. Locked out again. All my life that’s how I’ve felt. Locked out, not just from you, but everything. It was like life was happening for everybody else, and I could see it, but I couldn’t be part of it. I was left alone. And I’ve kept people away, afraid they would find out about you and think that I was like you. I’ve even kept you away, more than the prison’s bars and guards ever did. I was afraid to trust anyone. Including you. Including myself.

But that’s not why I’m writing this letter for the chaplain to give to you.

I know that Officer Watson’s family can’t forgive you. But I do.

I forgive you, Mother. Not for what you did, because that has nothing to do with me, and it’s not my place. I don’t know why you did what you did, but I don’t need to know. The important thing is that I forgive you for what you couldn’t do: be there to be my real mother. To raise me. To love me.

You’re still part of me. And I’m done being ashamed of that.

I love you. I forgive you. I miss you, but then again, I always have. And I always will.

Love,

Camila

19

OCTOBER 9 / FRIDAY / LATE EVENING / LINCOLN APARTMENTS

Camila was so tired every part of her body ached. But she knew she couldn’t go to bed. Instead she sat on the couch with Aunt Rosa and Aunt Maria, drinking coffee and watching the news. She hadn’t mentioned her prison visit this morning. Juan had gotten them back to Anaheim well before school let out, and they’d spent a few hours at his favorite coffee shop before she’d gone home at her usual time. Both aunts had assumed she’d been at school. She hadn’t had to lie. She was done lying. If it ever came up, she’d be honest about what had happened today.

“It’s a circus,” said Rosa, which was the first understatement Camila had ever heard her aunt make.

The cameras were stationed outside Folsom Prison now. And the protesters seemed to have moved with them. There were more people now than there’d been at the women’s facility this morning. An equal number on each side. The TV reporter, a pretty young black woman, struggled to shout over the noise surrounding her.

“This marks the first execution of a woman in two years, and the first in California … ” Camila couldn’t mute the TV, so she just stopped listening. Her mom wasn’t a story or a statistic. This wasn’t a cause or a reason for celebration.

Suddenly the reporter’s voice caught her attention again. “ … I’m speaking with Sophie Watson, the seventeen-year-old daughter of … ”

“Turn it up!” Camila gasped, leaning forward. Aunt Rosa picked up the remote and raised the volume a few notches.

Standing next to the reporter was a girl Camila recognized. It was the girl with long brown hair who’d been at Gina’s prison this morning. In her hand was a sign. It was now turned sideways, but Camila read it easily since she remembered the words: Mercy, Not Vengeance.

“I won’t be consumed by bitterness and hatred,” Sophie Watson said, her voice shaking with emotion. “My mother has never forgiven Gina Hernandez, but I’ve accepted my loss. The only thing to do is to replace the loss with something else. I can choose love and forgiveness over hate and bitterness. That’s how I’ve found peace.”

Camila looked away from the TV to glance at her aunts. Through the tears that blurred her eyes, she saw Rosa put a hand on Aunt Maria’s arm. Camila leaned over and wrapped her arms around Maria. Her aunt hugged her back. The reporter’s words faded, drowned out by the sobs of Gina Hernandez’s family.

20

OCTOBER 12 / MONDAY / MORNING / ANAHEIM HIGH SCHOOL

People knew. Camila sensed it the moment she walked into advisory.

“Why didn’t you tell us?” Lisa, with Angela, behind her, was the first to say anything.

“Tell you what?” Old habits died hard. Most things died hard, really.

“About your mom,” Lisa whispered.

“I’m so sorry for your loss,” said Angela.

Camila felt words jam up in her throat. She had no idea what to say, and even less idea what to feel.

“I lost my mom a few years ago to breast cancer,” Lisa said. “It’s hard.”

“For me, it’s my dad,” Angela added. “He’s alive, but not really part of the family. He’s been in and out prison most of my life. I see him every now and then, but it’s not the same.”

“I’m sorry, Angela,” Camila finally said.

“It’s not my fault, so you don’t need to feel sorry for me, but I appreciate it anyway,” Angela said. “Look, everybody’s parents make mistakes. S

ome get caught, and some don’t. We don’t judge.”

“How’d you find out about my mom?” Camila asked. “Did Steven tell you?”

“Who’s Steven?” said Lisa. Angela shrugged.

“Then how do you know?” Even as she asked, she prayed the answer wouldn’t be Juan.

“I don’t remember how it started, I think from somebody at Corona High who knew somebody who goes here, but this got sent around.” Lisa showed Camila her phone. It was a screen capture of Gina’s old yearbook photo, the one they’d shown on TV, next to a photo of Camila from last year’s Corona High yearbook. “You look a lot like your mom.”

“I know, but I’m nothing like her.”

“We wouldn’t know about that,” Lisa said. Camila’s eyes flashed in anger, and she stepped away. “Sorry, I didn’t mean anything bad.”

“She means we wouldn’t know that because we don’t know anything about you,” Angela said. “I mean, Camila, do you even have any friends?”

Camila didn’t answer the question. “Friends betray you.”

“Well, that’s the chance you take,” Lisa replied. “But you know, I’d rather take that chance then never be able to trust anyone. I mean that must be terrible. You must feel—”

“All alone in the world,” Camila said.

“I felt like that too sometimes,” Angela said. “First time my dad got locked up.”

There was genuine concern and caring in their voices. Camila wondered if she’d made a mistake—trying so hard to protect her secret that she had surrendered a good part of life. Maybe trust was like forgiveness. It had to be given freely. And freely received.

“We’re going to the mall later. Do you want to come with?” Lisa asked.

“Why, you need a necklace you want me to steal?” Camila snapped back.

“No, we just thought you’d like the company,” Lisa answered. “I know after my mom died, I just wanted to be left alone, but I realize now that was the worst thing in the world.”

Camila held in her tears and nodded. OK, I’ll give it a try. I’ll give them—and myself—a fair chance. She allowed herself to smile at the thought of finally unlocking her life.

Head Kick (The Dojo)

Head Kick (The Dojo) Duty or Desire

Duty or Desire Returning to Normal (Locked Out)

Returning to Normal (Locked Out) Things Change

Things Change Controlled

Controlled Friend or Foe

Friend or Foe Stolen Car

Stolen Car Heart or Mind

Heart or Mind The Franchise

The Franchise Triangle Choke (The Dojo)

Triangle Choke (The Dojo) #1 Out of the Tunnel

#1 Out of the Tunnel Chasing Tail Lights

Chasing Tail Lights Nailed

Nailed Combat Zone

Combat Zone Outburst

Outburst Barrier

Barrier Fight or Flee

Fight or Flee Doing Right (Locked Out)

Doing Right (Locked Out) Cheated

Cheated Guarding Secrets (Locked Out)

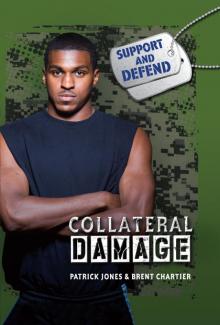

Guarding Secrets (Locked Out) Collateral Damage

Collateral Damage On Guard

On Guard Always Faithful

Always Faithful The Gamble (Bareknuckle)

The Gamble (Bareknuckle) Side Control (The Dojo)

Side Control (The Dojo) Bridge

Bridge Body Shot (The Dojo)

Body Shot (The Dojo) The Tear Collector

The Tear Collector Slammed

Slammed Drift

Drift Pass It Forward

Pass It Forward Target

Target Freedom Flight

Freedom Flight Taking Sides (Locked Out)

Taking Sides (Locked Out)