- Home

- Patrick Jones

Taking Sides (Locked Out) Page 3

Taking Sides (Locked Out) Read online

Page 3

Todd decided to change the subject. “Coach, I’m sorry I missed the meet yesterday. I couldn’t call. Everything was happening so fast and—”

“Don’t worry about that right now, Todd,” said Coach Colter. He had an odd look on his face. Embarrassed, almost.

“So I’m still on the team? Even though I no-showed?”

“Well … uh … ” Todd could tell that wasn’t a yes.

Coach Colter looked at Dr. Marsh, who finally spoke. “These are very unique circumstances, Todd. Do you intend to continue at Green River Academy?”

Todd didn’t like the tone. It sounded to him like the answer she wanted was no. “Of course. I mean, I know I’m late today, but that was just because the bus was running behind schedule.”

“We’re not even sure who to talk to about this,” said Dr. Marsh carefully. “Who are you living with?”

Todd explained the Sorensen placement in as few words as possible.

“OK,” said Dr. Marsh. “We’ll need to do some following up. I can’t promise anything until I know more.”

“What do you mean?” asked Todd. “You don’t need to promise anything. I’ve already said I’ll take the bus here every day. I won’t be late again … ”

“Todd, we just wonder if—with everything happening—if Green River is the best place for you.”

“What do you mean? Of course it is. All my friends are here. And my whole family’s gone here—my dad went here.”

“Yes, and that’s why we’ve allowed you to continue without interruption this year, even though your father—” Dr. Marsh stopped speaking suddenly.

“What about my father?”

“He hasn’t paid your tuition yet for the year,” Marsh said, sounding embarrassed, even though Todd felt the humiliation was all his. “I thought you knew.”

The adults continued talking about what was best for Todd, as though he wasn’t sitting in front of them. As he listened, it suddenly hit him. When Dr. Marsh had asked if Green River was “still the best place” for Todd, what she’d really wanted to know was whether Todd could afford Green River’s high tuition. That was what they were really worried about. He felt his face grow hot.

Todd reached down for the gym bag that held his wrestling gear and tossed it at Coach Colter’s feet. “Can I go now?” he asked.

Dr. Marsh nodded, a tiny gesture, almost like she didn’t want the other adults to see it. They don’t want me here, Todd thought. Some Green River family.

Todd left the office and took off toward his locker. The bell rang for the end of first period and suddenly the hallways were swarming with people—students, teachers, staff. It seemed like everyone was either deliberately not looking at him, or staring at him. He saw two girls point, whisper, and laugh. As if anything was funny about what was happening to him. Suddenly, he switched direction and headed toward the ninth grade section. Like a cop on a stakeout, he planted himself next to Tina’s locker.

As Todd half-expected, Tina didn’t show up. Then he spotted Tina’s best friend Ashley down the hallway, in the center of a group of girls. With a burst of speed, Todd cut into the group. “Ash, where’s Tina?”

11

The bus ride from Green River back downtown and then south to Southeast High School seemed to take forever, maybe because Todd had so much on his mind. He wasn’t sure about going back to Green River, but he was positive he needed to see his sister. Ash hadn’t given up Tina’s new school, so Todd had gotten the info from one of her other friends who had a crush on him.

Unlike Northeast High, which he had no intention of attending, Todd had been to Southeast for sports events. He’d won his first wrestling match as a freshman at a Southeast meet. Although most of his buddies played basketball as their winter sport, Todd’s dad pushed him toward wrestling, as well as cross country and track. (Even if your team loses, you can still win. You don’t need to rely on anyone but yourself. That’s a good life lesson, Junior.)

Todd knew he couldn’t get into the school, so he waited across the street. He texted Benton and other wrestling buddies, asking how the meet had gone, but no one texted back.

An hour later, high-schoolers were pouring out the front doors. Todd immediately called his sister’s phone.

The call went to voicemail. Todd wanted to leave another message, but Tina’s mailbox was full. Had she listened to any of his messages begging her to talk to him? Why wasn’t she returning his calls? Was it her choice, or were the police not allowing her to call?

And then he saw Tina emerging from the front door, alone, her head down. He’d have his answers soon.

Pushing his way through the crowd, he shouted her name. Tina stopped, stared at Todd for a second, and then started running. Even though she dropped her book bag to gain speed, Todd was faster. He caught her by the curb and grabbed her arms. “Tina, why are you running from me? Why won’t you answer my calls?”

Tina refused to look at him until he forced her chin up. She was crying. Todd wondered how many times she had cried during the last week. Had she ever stopped? “Tina, you have to listen to me.”

He placed a hand on her shoulder, just like his dad used to do. “I’m not sure what you think you saw, but you’ve got it all wrong. Mom came at Dad. He was defending himself, protecting us too. You’ve got to tell the police the truth. You—”

“Todd, leave me alone!” Tina shouted. “I can’t talk to you. I won’t talk to you!”

“Tina, listen, you’ve got to do the right thing here, for me, for you, for Dad. If you—”

“He killed her, Todd!” Tina started to shout more, but tears choked out her words.

Todd’s clasped both his sister’s shoulders, just as his coach would do before a match. He needed to get her focused, to get her to listen to him, to their dad. “Listen, Tina, it wasn’t his fault! Anyway, nothing we do or say now can bring her back. But we can bring Dad back.”

“You think I want him back?” Tina screamed.

“He’s our family! That’s what matters—”

“What matters,” Tina shrieked at the top of her lungs, “is our dead mother!”

Todd could ignore Tina’s words, but not her tears, falling fast. He loosened his grip on her. “Todd, why aren’t you upset?” she demanded. “Why are—”

Todd cut her off. “She’s gone, Tina. Dad’s still alive. He’s the one that we—”

Tina tore herself away from her brother. Todd stood frozen for a moment, long enough for Tina to scoop up her book bag and head back toward the school. “Tina, wait! Just wait—”

It only took him a second to overtake her again. He spun her around—she was sobbing so hard her whole body shook.

A deep male voice yelled, “Hey! Let her go!” Some teacher guy was running toward them.

“What’s going on here?”

“She’s my sister … ”

“No!” shouted Tina, pushing him away again. “Get away from me.”

“Tina, what are you—”

“Get away!” she yelled as the teacher guy stepped between them. “Just stay away!”

“No, listen,” Todd said desperately, speaking to the teacher now. “She’s my sister, I just want to talk to her for a minute.”

“I’m not!” Tina shrieked from behind the teacher. “He’s not family!”

“Look, I can prove it!” Todd pulled out his phone and pulled up a photo of the two of them together—a selfie he’d taken a few weeks before, just after a wrestling meet she’d come to with her friends. “See, there we are together—”

In a tear-choked voice, Tina talked over him. “He’s my ex-boyfriend, OK? He’s been stalking me. Please, can you just call the police?”

Todd gaped at her. How could she be so afraid of him that she would say something like this? “Tina—!”

The teacher was already ushering her back toward the building. “Come on, let’s get you inside first,” the guy said in a low voice Todd wasn’t meant to hear. As soon as they got back into t

he school, the teacher would probably do exactly what Tina had asked—call the police.

“It’s not true!” Todd shouted after them. “She’s lying! I’m telling the truth!” Then he swore under his breath and took off running.

12

It was the call he’d been dreading. Unknown caller. His father. Todd didn’t want to answer, but knew he had to, if only to hear his dad’s voice again. He picked up and struggled to hear through the chatter of the other bus riders and their screaming children. Out of the corner of his eye, Todd saw two young kids, a brother and sister, at their mom’s feet. The mom had a phone pressed to one ear, and covered her other ear to block out the sounds of her kids.

“Junior, it’s Dad. Have you seen Tina?”

“Yes, sir.”

“And?”

Todd paused and thought for a second about hanging up, jumping off the bus at the next stop, and running. With his cross country endurance, Todd knew he could run a long, long time.

“Junior, are you there?” His father said. “Answer me.”

Todd imagined the hard look on his dad’s face when he told him he’d failed. He’d seen it so many times that it was burned on his brain. Jaw set tight, dark eyes flat. It was the look that said, “Todd, I’m not mad at you, just disappointed.”

“I saw her,” Todd confessed.

“And?”

Todd told his father about his talk with Tina, including Tina denying that she knew him.

“You see what I mean, Junior,” Dad says. “She lies. You tell that story to the police.”

“Why should I talk to the police again?”

“I’m coming in. My lawyer told me that if you couldn’t make your sister understand the truth, I’d have to surrender. Since you couldn’t do what I asked, I have no choice.”

“I’m sorry I let you down,” Todd choked out. He tried to imagine the look on his father’s face. Was it still the scowl of disappointment? Or was there a glimmer of understanding? Of acceptance? Todd wanted to join the children crying at their mother’s feet on the bus. “Dad, what’s going to happen?”

“I’ll get booked at the county jail, arraigned, and then post bond. I’ll be out by morning.”

“Can I see you?”

Todd’s father didn’t answer. It sounded like he had his hand over the phone and was having another conversation. Who was he talking to? Where was he? But even as Todd asked himself these questions, another one emerged: Why doesn’t he ask about me? His father hadn’t asked how he was doing, where he was living, anything.

“My lawyer says it’s complicated, but he understands the system better than I do.”

The System. Just like “the County,” but bigger.

The bus pulled into the downtown bus mall where he’d transfer to the next bus, to take him to the next transfer, and then to Sorensen’s place.

“I’ll try to talk to Tina again, if that’s what you want,” Todd said as people pushed past him.

More muffled conversations. Todd followed the mom and her crying children off the bus. “Don’t. My lawyer says you might get me into trouble for witness tampering. Might make it worse.”

“Witness tampering?”

“My lawyer found out that Tina’s talking to the police. I mean lying to them,” Dad said.“If it goes to trial, your sister is going to testify against me.”

With that, the line went dead. Todd paused on the sidewalk. Stared at the phone. His dad had hung up on him. Given up on him.

Well, I’m not giving up yet. Todd opened the map feature on his phone and pulled up directions to the county jail.

13

Todd shivered in the cold outside the Sorensen house. Just as the rule book said, if a resident wasn’t in by curfew, he’d find the door locked. Todd had waited all night for his father to show up at the jail, but he never did. When Todd had gone inside to inquire, the jail staff had been no help. Tired and discouraged, Todd had taken another long bus ride, only to find himself locked out.

When the door opened the next morning for the other foster kids to leave for school, Todd raced inside. “I’m giving you a one-time pass since you seem like a good kid,” Sorensen said. “It happens again, you’re out.”

Todd nodded. He didn’t want to waste a single word, an ounce of energy on Sorensen or the other soul-crushing cogs in The System. He ducked into the kitchen, grabbed a cola from the fridge, and gulped it down. Then he went to the room he shared with a city kid named Antonio. It was a mess—like there had been a party there without him.

Todd grabbed clean clothes, took a quick shower, and raced back to the kitchen. Still tired, he filled a Styrofoam cup with the sludge that Sorensen called coffee. Still, it was warm caffeine. He drained the cup, then filled it again.

“That’s a dollar,” Sorensen said.

Todd pulled out his wallet. It was empty. “I’ll pay you later.”

“Price goes up later.”

Todd recalled seeing an ATM near the downtown bus stop. He’d be tardy for school anyway, so what difference did another ten minutes make? What difference did anything make?

“Make sure you check out the chore wheel,” Sorensen said as Todd bounded out the door. I hate this, Todd thought. The chore wheel, the caffeine cost, Sorensen, his house, his rules, all of it.

On the bus, he tried playing games on his phone, but it was too noisy, and he was too distracted. He found the app for the local newspaper, downloaded it, and saw the story. His father had surrendered to police early in the morning and was being held in the Public Safety Facility, some fancy name for the jail, pending his arraignment and bond hearing.

When the bus finally reached downtown, Todd raced to the ATM. His dad had set up an account for him and put in twenty dollars each week. If Todd didn’t spend the entire twenty, his dad would give him more next week, so he’d built a cash reserve. Lately, as his parents fought more, his dad put extra money in. Todd pushed in his card, typed the code, and hit the button to withdraw twenty. The screen flashed “insufficient funds.” He took out the card, started over, and got the same result. He started to try it a third time when he heard a man’s irritated voice behind him. “Kid, I’ve got places to go. Let’s move.”

Todd put the card back in his wallet and raced toward his next bus, but he arrived just in time to see it leaving. The next one was in twenty minutes. Hating to waste time, he hustled back to the jail, went inside and waited in a long line to speak to the person at the desk. “I want to know when I can visit my—”

The uniformed man pointed at a sign which showed visiting hours: Monday 6 to 10 p.m., and Wednesday, Friday, and Saturday 8 to 10 a.m. Today was Thursday. “How do I visit?”

The answer this time was a sheet of paper and another set of rules. At least there are no Bible verses, he thought. Todd started to ask another question, but the guard looked past him and yelled “next.” Todd knew that look pretty well by now. A lot of people had turned out to be pretty good at acting like he didn’t exist. He stepped out of line and glanced at the sheet that read “Visitors under 18 must be accompanied by a parent or legal guardian.” If my dad’s in jail and my mom’s dead, Todd thought, who is my guardian?

14

When Todd arrived at the school, he went directly to Dr. Marsh’s office.

“Todd!” Dr. Marsh looked surprised to see him. Maybe even a little nervous? But no, he was imagining that. Dr. Marsh wouldn’t be frightened of him, would she? “Come in. Have a seat. What can I do for you?”

“Did you do your following up?” Todd asked, borrowing the phrase she’d used the day before. “Do you know who my legal guardian is? Is it Sorensen?”

For all her degrees, Dr. Marsh seemed puzzled by the question. “I’m still not sure. I haven’t had a chance to look into your situation more closely … ”

Todd reached into his wallet. He pulled out the business cards of all the social workers he’d come in contact with the past week. He placed them on the table like he was dealing poker. “Or mayb

e it’s one of these people. I need to find out so I can visit my dad.”

Dr. Marsh studied him for a few seconds. “Do you think that’s a good idea?” she said. “I mean given the circumstances.”

Why does she use that word so much? Todd asked himself. “He’s innocent,” Todd snapped, for what seemed like the millionth time.

Dr. Marsh’s shoulders tensed. The way his mom’s used to, when she was expecting a blow. “I’ll see what I can find out, Todd,” she said. “About your legal status. But for now, maybe it’s best if you go to class and just try to get through the day.”

Dr. Marsh seems to care, Todd thought. But that’s her job. None of these people really cared about him. And he couldn’t visit the only person who did care. He slammed the door when he left Dr. Marsh’s office, and then the door to the office suite. Todd wanted to walk down more halls, find more doors, and slam them all.

He couldn’t wait to get to his locker, if only to slam it shut. As he got close, he saw something taped to it. It was a sympathy card, signed by the wrestling team. Some standard lines about being “sorry for your loss.” Still, he had to hold back tears as he read it.

Then he felt a tap on his back. “Todd—sorry, man.” It was Benton. Benton, who hadn’t returned any of his calls or texts.

“Thanks, Bent.” Todd had only so much anger left and didn’t want to waste it on Benton.

“Man, we’ve got the out-of-town tournament this weekend, or we’d be there for you.”

“Be where?”

“At your mom’s funeral.”

“When is it?” Todd asked. No one had told him. How could that be?

Benton blinked a couple times—no other sign of surprise. Benton was tough to rattle. Once, Todd would’ve said the same about himself. “Saturday morning at ten, but like I said, we’ll be out of town. Sorry, man.”

Todd nodded, opened the locker, took out nothing, and slammed the door. The jolt of it shot through his system like he’d been taken down in a match.

“Bent, can I ask you something?”

Head Kick (The Dojo)

Head Kick (The Dojo) Duty or Desire

Duty or Desire Returning to Normal (Locked Out)

Returning to Normal (Locked Out) Things Change

Things Change Controlled

Controlled Friend or Foe

Friend or Foe Stolen Car

Stolen Car Heart or Mind

Heart or Mind The Franchise

The Franchise Triangle Choke (The Dojo)

Triangle Choke (The Dojo) #1 Out of the Tunnel

#1 Out of the Tunnel Chasing Tail Lights

Chasing Tail Lights Nailed

Nailed Combat Zone

Combat Zone Outburst

Outburst Barrier

Barrier Fight or Flee

Fight or Flee Doing Right (Locked Out)

Doing Right (Locked Out) Cheated

Cheated Guarding Secrets (Locked Out)

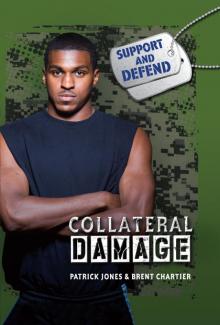

Guarding Secrets (Locked Out) Collateral Damage

Collateral Damage On Guard

On Guard Always Faithful

Always Faithful The Gamble (Bareknuckle)

The Gamble (Bareknuckle) Side Control (The Dojo)

Side Control (The Dojo) Bridge

Bridge Body Shot (The Dojo)

Body Shot (The Dojo) The Tear Collector

The Tear Collector Slammed

Slammed Drift

Drift Pass It Forward

Pass It Forward Target

Target Freedom Flight

Freedom Flight Taking Sides (Locked Out)

Taking Sides (Locked Out)