- Home

- Patrick Jones

The Franchise Page 3

The Franchise Read online

Page 3

“I don’t really know how to scout or evaluate talent,” I admitted.

“Skill is skill is skill.” Milliken pointed at my computer. “Run the numbers. Gather all the data, and not just football stuff. Get their grades, anything you can find out.”

“How about their injury history?” I asked.

“If you think that’s important, but I tell you, most kids today aren’t as tough as the old-timers. You know why they gave Frank the nickname ‘Franchise’? He didn’t miss a game in seventeen years, not one. Most kids can’t go seventeen days without needing a Band-Aid for something.”

“I’ll see what I can find out about injuries, especially concussions—”

Milliken snorted. “Don’t bother with that. If we drafted players who never had concussions, we’d have a team of punters. Concussions are as much of part of this game as cheerleaders and tailgate parties.”

I cracked my knuckles so as not to ball them into a fist and punch Milliken. I’d lose my scholarship and internship, but maybe he’d experience what a concussion fog felt like.

“So, next Saturday, before we head to Dallas, watch the MSU–Ohio game, crunch the numbers,” Milliken said with a smile he seemed to switch on and off. “If I like your report, I’ll let you pitch your system to Schultz.”

“Thank you, Mr. Milliken. I appreciate—” was as far as I got before there was another call.

I looked at the scoreboard. The Stars were losing, which was bad, but I knew two things: I’d won another opportunity, and, from my research, beer sales would be good.

ELEVEN

September 12 (Wednesday)

“Here’s your opportunity, Latrell,” Milliken said as the door to his office opened. In walked Smackdown Schultz, whistle around his neck, clipboard in hand, his eyes looking through me like I was an empty space cleared by an offensive line.

“You wanted to see me?” Schultz asked Milliken.

Milliken sat at the conference table in his office. I sat next to him, computer open.

Schultz remained standing, his arms folded across his chest, clutching the beat-up brown clipboard like a precious object. He’d probably had the thing since his first coaching gig a decade ago.

“As you know, Holt gave Latrell an opportunity to intern in the GM’s office. He was selected because…well, Latrell, you take it from here.”

I tried to make eye contact, but Schultz wasn’t having it. I took a deep breath, then started. “Um, I developed a system that predicts the best possible defensive play based on—”

Schultz interrupted. “Is this kid’s internship with you or with me?”

Milliken said nothing. It was all on me.

“It’s with the GM’s office,” I answered.

“GM runs the business,” Schultz said, his voice gruff. “Coaches run the team.”

“I thought you might consider using my system just once,” I said, almost whispered.

“How many NFL games have you played? How many have you coached? How many hours of game film have you watched?” If Schultz was on the field, he’d have thrown the clipboard at my feet, I just knew. “Let me answer for you: zero, zero, zero. You put points on the board and scars on your body, then maybe I’ll listen.”

“But Frank thought—”

Schultz snorted. “Frank doesn’t think.”

I wasn’t going to let that go. “If Frank and I worked together, if you gave me a chance to call one set of downs—”

“Listen, kid, Frank Foley can’t even choose which socks to wear. He’s not calling plays for me, and neither are you.”

I swallowed hard. “We could contribute if you let us.”

Schultz looked hard at Milliken. “Some people earn what they get. Others have it handed to them because someone else wants to feel good about themselves.”

Milliken looked up from his phone. “That’s enough, Joe.”

Schultz and Milliken locked eyes. This wasn’t about my system, but something bigger. I’d read that Shultz wanted to be head coach, but Milliken hired media-friendly Allen instead.

“You give me better players, I’ll give you better results,” Schultz said.

Milliken switched on his smile. “Harmon Holt’s name is on your paycheck, and he wants—”

“He wants a winning team,” Schulz cut in.

“No, he wants to make money,” Milliken said in the tone of a third-grade teacher. “And since it’s his money to begin with, he calls the shots. Think about that before this Sunday.”

“Are we done?” Schultz asked.

Milliken nodded, but I sensed this wasn’t the end of anything, just the beginning.

Schultz left the room while Milliken looked down at the carpet. I knew then what it felt like to be on the fifty-yard line: right in the middle of the action.

TWELVE

September 15 (Saturday)

“Thanks for letting me bring my dirty clothes,” I told Roxanne.

“Sure thing,” she said.

As she loaded the dryer with the clothes I’d take to Dallas, I gazed at the football shrine that was Franchise Foley’s basement. There were photos of great plays and endless trophies in a cabinet. One corner must have had fifty jerseys, hanging from a rack. In another corner stood a life-size cardboard cutout of Frank at the height of his career, smiling, holding his helmet against his hip.

Roxanne finished loading the dryer and joined me in the shrine. “Dad has lots of memories down here.” She walked to the jerseys and touched one. “He’ll come down here and sit for hours with the lights off.”

“Why with the lights off?”

“He says he can hear the crowd that way.”

It made me think. Seventeen seasons, every Sunday, playing at the bottom of a Miami or Denver or Buffalo stadium bowl, thousands of eyes on your every move.

Roxanne stood in front of me and grabbed my hands—not in a romantic way, but like she was hanging on for dear life. “Promise me you’ll look after Dad in Dallas.”

“No problem.” I laughed when I said it, but she looked at me hard and serious.

“No, you have to stay with him. That place is huge. He’ll get lost in the stadium if you don’t.”

It was sad, listening to Roxanne talk about her dad like he was two years old, like he was the child and she was the parent. Did that make me a babysitter? “I’ll stick with him, Roxanne.”

She raised her hand and touched my face. “Thank you,” she said. She leaned in. I leaned in soon after, and there, in the shrine to her absentminded father, we kissed.

She drew back. “When you come back, we can spend time together, maybe go to a movie.” Her lips felt soft.

I leaned in. Before our second, longer kiss, I said, “I like movies, too.”

Frank called from the top of the stairs. “Latrell, MSU just kicked off to Ohio State.”

I giggled, and Roxanne did, too. We’d just had our own kickoff of sorts.

On the plane to Dallas, Frank squeezed his big frame into the small seat. “It was good that Roxanne saw us off at the airport,” he said, “I think she likes you.”

A wave of nervous energy came over me. “What makes you say that?” I asked.

“You think I didn’t see you two kiss before you got to the gate?”

I shrank in my seat. You hear stories about fathers who don’t like guys who date their daughters. Few guys date daughters whose fathers crushed offensive linemen for a living.

I had to say something. “I hope you don’t mind, sir.”

“Not at all. I just want her happy.” He paused. “Roxanne probably told you. Doctors say I have brain damage from all the hits I took. But would I trade losing my car keys for all that football gave me? Probably not.”

I wondered what price I’d pay to succeed at something I loved.

“I can always find another set of car keys, but I couldn’t get another one of these.” He put his hands in front of me to show off the Super Bowl rings. “But it’s not about the rings, eithe

r.” He closed his eyes, tilted his head back, and smiled. “It’s the roar of the crowd.”

THIRTEEN

September 16 (Sunday) Dallas Cowboys

“They’re killing us with junk,” I told Milliken as the Cowboys completed another short pass for another first down. I looked at my laptop from the comfort of the suite reserved for visiting GMs. The Cowboys had converted almost every third down in the first half, and the second half started out the same. The Stars defense leaked like a broken boat.

“So, who did you like?” Milliken asked. “The kid from MSU or Ohio State?” Had he written off the season after just a game and a half?

“It depends on what kind of player you want. The guy from MSU has more interceptions and can run the defense. But the Ohio State guy is just a monster, a running back–eating machine.”

“Who did Frank like?” As soon as he asked the question, he answered. “Let me guess, the kid from his alma mater who plays like he did?”

“Hands down,” I said. Frank trusted my system, but he trusted his gut more.

“We sure could use him now,” Milliken shouted over the crowd’s roar. Another Dallas TD.

I took a deep breath. “Let me call the next third down situation. I’ll make the right call.”

Milliken shook his head. “Schultz won’t listen to you.”

I stood up. “Then make him.”

Milliken picked up the phone connected to the coaches on the field. He put his hand over the receiver. “But Joe might listen to Frank, out of a sense of loyalty.”

I looked at the field. Frank paced on the sidelines, seemingly more agitated than delighted by the roar of the crowd. I looked at Frank, then at my computer, and waited. After the kickoff, the Stars got shut down: an incomplete, a busted sweep, and another quarterback sack. The Stars’ punter had more time on the field than the quarterback.

The Cowboys went right to work with two short passes for first downs that got them into scoring position. I added the data and waited. Milliken held the phone in his hand. First down, incomplete. Second down, four yards on a screen. Milliken handed me the phone. It was third and six from the forty, an important down for them and me.

As I looked at Milliken, I spoke to Frank. “This play, call a weak side, CB blitz.”

Frank grunted his approval. On the field, I could see him whisper to Schultz. I held my breath. It seemed like the longest snap count in history.

After the snap, the Dallas QB took two steps into the pocket before the Stars’ cornerback slammed hard into him, knocking the ball loose.

“Go! Go! Go!” Milliken and I shouted at the same time.

Sims scooped up the fumble, turned on his speed, and never looked back. Not only had I called my first play, I’d scored my first TD.

On the field and on the sidelines, the Stars players celebrated. I watched as Schultz gave Frank a friendly slap on the back. Frank turned in the direction of the suite, looked up, and waved.

FOURTEEN

September 24 (Monday) San Francisco 49ers

“There’s nothing like Monday Night Football,” Milliken said. Once again, the GM’s box was filled with his friends and front-office staff. “In L.A., you get a different crowd on Monday night because the game starts early for the nine o’clock, East Coast start time. New crowd, new revenue.”

Milliken rambled on about monetizing opportunities, sounding more like a banker than a football guy. Maybe for him it was all the same.

Although the Stars’ offense managed a field goal in their first possession, they’d need more than that. The 49ers’ defense was weak, but their offense was among the strongest in the league. They used a classic run-and-shoot: four receivers, no fullback or tight end. It spread out their offense and was a nightmare to defend. Another wrinkle made them even more deadly: their QB ran like a halfback. They’d won their first two games by thirty. Predictions were they’d win this game by as much. Unless.

At the half, the Stars were down by fourteen as the offense finally clicked. Milliken left the GM box and went to the locker room. Everyone else cleared out with him, leaving me alone. Below me were sixty thousand fans, many thinking that if they cheered loud and long enough, it would make a difference. They acted on faith, not science or facts.

Milliken returned five minutes into the third quarter. After another 49er TD, he took a seat in the recliner. I typed, the crowd roared, but Milliken remained silent until the start of the fourth quarter. “Tell me what play they’ll run and what we should do.”

I relayed the information, but the phone to the coaches’ box stayed untouched. Down after down I told Milliken what we should’ve done, but on the field, Schultz used old-school D. My computer crushed his clipboard like the 49ers crushed the Stars.

FIFTEEN

September 30 (Sunday) Baltimore Ravens

“It’s good to have you home,” Mom said. Grandma Estelle, Randall, my aunts, uncles, and various cousins all agreed. “I’m glad the team let you spend the night.”

“It’s probably so they could save on the cost of a hotel room.” Everyone laughed, but I was serious.

“I thought we’d see your name in the paper or on TV.” Mom sounded disappointed.

“The stars of the team are the Stars players.” I thought one white lie was okay. I saw football as a game of strategy, like chess. Milliken did too, as he pushed around interchangeable pawns. The difference was, I cared if the pawns got crushed.

“We’re all so proud of you,” Mom said, beaming. “This is your opportunity to do what I couldn’t do.”

“What’s that?”

“Get out of here.”

“Why would I want to?” I asked.

Mom shook her head. “You’re meant for bigger things than this,” she said. She passed around the bowl of scrambled eggs. There was no ham, no bacon, just eggs. It was all she could afford. Back at the Hilton Baltimore, I knew the players were dining on a five-star brunch. As I scooped up another forkful of eggs, they never tasted so good, and my family never felt so strong.

“Where’s Frank?” I asked Earle, the equipment manager, when I entered the locker room. I wanted Frank to meet my family.

“Try the weight room,” said Earle.

With the game less than an hour away, I went to the weight room. The lights were off. When I clicked the switch, there was Frank, sitting on a bench in the corner. His eyes were closed, and he was wearing the biggest pair of earphones I’d ever seen.

I tried to get his attention, but he didn’t respond. It scared me.

Then Schultz came into the room, kneeled down, and tapped Frank’s leg with his clipboard.

Frank pulled his earphones off. Under the earphones, he had earplugs. He pulled those out, too. His ears were open, but his eyes were closed, shut tight as though the faintest amount of light would hurt.

“Getting to be too much for you?” Schultz asked.

“Sometimes I just have to shut it all down,” said Frank.

“Are you able to join us on the field today?” Schultz asked. Frank nodded and handed the plugs to Schultz. Schultz looked puzzled. “Why are you giving these to me?”

“Might as well make it official. You don’t listen anyway.”

“Frank, once the game starts, it’s my defense. You had a good call during the Cowboys game, but—”

“It wasn’t mine, it was his.” Frank pointed at me. His hand shook just like my knees.

“We’re oh and three on the season. You really want to go oh and four?” Frank asked.

Schultz said nothing.

Frank stood up and put his arm on my shoulder.

I took the opportunity to speak. “The Ravens offense has weaknesses we can exploit. The left side of their line is—”

Schultz cut me off. “I watch the game films, too. Tell me something I don’t know.”

I took my cue. “In their first three games, they—” I started. I went on for a good two minutes, giving him the hard sell on everything I knew to help u

s win.

Schultz thought for a moment, then spoke. “I’m the defensive coordinator, not you, kid. And not Frank,” he said, brow furrowed.

“Frank and I have the system. I ran the numbers. He watched the film. We can do this.”

Frank jumped in. “He’s right, Joe. The kid’s system works.”

I didn’t like it when Schultz called me a kid, but coming from Frank, it was okay. We were partners, trying to bring sight to the sightless.

Schultz paused. “I know you have problems, Frank,” he said.

“My problem is the guy I played beside for almost a decade doesn’t trust my football judgment,” Frank said. “Trust us, Joe.”

Schultz sighed.

“You’re winless,” I said. “You have nothing to lose.”

Another sigh, only bigger, meaner. “Okay,” Schultz said with a scowl on his face, “but I have two conditions.”

“Name ’em,” Frank said as he sat back down.

“We keep it between us. No one on the team and no one in the media learns about this, got it? I can’t have my defense becoming some sideshow.”

“Milliken has to know.” Frank put his hand out. Schultz dropped the earplugs in his palm.

“Between the four of us, then,” Schultz said. “But if things start to go wrong, I take over.”

“Fine.” Frank closed his eyes and put the plugs back in his ears.

“And another thing—” Schultz started.

Frank cut him off. “Here’s my condition. Turn the lights off on your way out. Come get me when it’s game time.”

SIXTEEN

October 1 (Monday)

Every phone in the Stars’ front office rang all morning except mine. The ancient beige phone in the tiny conference room Milliken had arranged to be my “office” was silent. And when I tried to get in to see Milliken about next week’s game or another assignment, I was told he was too busy.

Head Kick (The Dojo)

Head Kick (The Dojo) Duty or Desire

Duty or Desire Returning to Normal (Locked Out)

Returning to Normal (Locked Out) Things Change

Things Change Controlled

Controlled Friend or Foe

Friend or Foe Stolen Car

Stolen Car Heart or Mind

Heart or Mind The Franchise

The Franchise Triangle Choke (The Dojo)

Triangle Choke (The Dojo) #1 Out of the Tunnel

#1 Out of the Tunnel Chasing Tail Lights

Chasing Tail Lights Nailed

Nailed Combat Zone

Combat Zone Outburst

Outburst Barrier

Barrier Fight or Flee

Fight or Flee Doing Right (Locked Out)

Doing Right (Locked Out) Cheated

Cheated Guarding Secrets (Locked Out)

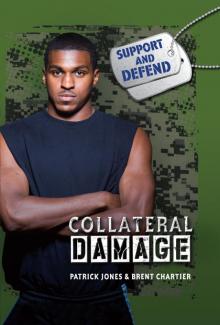

Guarding Secrets (Locked Out) Collateral Damage

Collateral Damage On Guard

On Guard Always Faithful

Always Faithful The Gamble (Bareknuckle)

The Gamble (Bareknuckle) Side Control (The Dojo)

Side Control (The Dojo) Bridge

Bridge Body Shot (The Dojo)

Body Shot (The Dojo) The Tear Collector

The Tear Collector Slammed

Slammed Drift

Drift Pass It Forward

Pass It Forward Target

Target Freedom Flight

Freedom Flight Taking Sides (Locked Out)

Taking Sides (Locked Out)