- Home

- Patrick Jones

Barrier Page 2

Barrier Read online

Page 2

“Jessica, we’re going to start with a diagnostic instrument that will give me the information I need to help us put together a treatment plan, if that’s what’s called for.”

“What do you mean if?” I asked. She set the clipboard down and leaned closer to me.

“I believe you were referred by the school counselor at Harding, and she—”

“I don’t go to Harding anymore.”

“Really?” She wrote that down on the pad of paper now resting against her knee. “Why?”

I told her that story. I told her all about Rondo and my ninth-grade hell at Verdant Hill, spoiled rich-kid central out in the burbs.

“You don’t seem to have any problem talking to me!” she joked.

I laughed, not too loud. “That’s because you already know that I’m crazy, right?”

“You think you’re crazy?” she asked calmly. She scribbled on the pad again. She started to speak but then stopped. It was like when Dad and I played chess. He’d be touching the pawn for minutes but then move the knight. “So, tell me a little bit about your family history.”

I gave her that story too. “My dad was from here in St. Paul, but he played football on scholarship at a small college in Texas. My mom was from the college town, Stephenville. I don’t actually know how they met. They never told me, and I guess I never asked. I do know that not long after they met, they ran away and got married, and then I came along seven months later. So, I guess they had to get married back then, especially in a small town like that.”

“When did you move to St. Paul?” she asked.

“Well, Dad dropped out of college and got a job doing computer stuff,” I said. “We moved here just before I started fifth grade, partly to be near my grandfather, who was sick.”

“That must have been traumatic for you, moving away from your friends.”

I paused. She had to bring up those memories of having friends. “I had lots of friends in Texas, and I didn’t want to move, but it’s not like I got a say or anything.”

“How about once you moved here? Did you make friends right away?”

Another pause. “Well, at first, but then …”

“But then?”

“In junior high, everything changed. I don’t know why.”

“The transition from elementary school can be very difficult for lots of children,” she said, as if to reassure me that I was normal. As if. “Did you make new friends in junior high?”

The box of tissues was out of reach. Fine—I would just use my long sleeves. “Not really.”

Like some mind reader, she handed me the tissues. “Do you know why?”

I wanted a great story to tell her. Some shower room ordeal like in the movie Carrie, or an embarrassing nipple-slip, but no. I had no drama, no trauma, just no friends. “No. I don’t.” The tears spilled over.

She let me cry for a while. Finally, she said, “Jessica, we need to do this test.”

I sucked it up. I felt like I’d just taken one, except I didn’t know if I had passed or failed.

6

EIGHTEEN QUESTIONS THAT DEFINE MY LIFE

“I’m going to present you with eighteen social situations,” Nina Martin said. “I want you to tell me—on a scale of zero to three, with three being the highest—how much stress you feel in each situation. Also, on the same scale, how much you avoid each situation.”

I nodded. I’d known this was coming. The second I’d gotten home from the Harding counselor’s office, I started to look up stuff online about social anxiety disorder. She was using something called the Kutcher Generalized Social Anxiety Disorder Scale for Adolescents. I’d printed it out and studied it. There was one big question for me to consider over all eighteen items: did I want to answer honestly and maybe deal with all this, or should I just lie and avoid it?

“Even though we’re running late, I want you to take your time answering,” she explained, trying to sound so reassuring. “Some people need more time to process.”

I laughed to myself as I thought about Mom agonizing over which salad dressing to buy, or Dad alone in the basement all the time on his computer, and me turning into them. They were isolated, paralyzed by indecision.

“Remember, scale of zero to three. Ready?” My firm nod was the go-ahead sign.

“One: initiating conversation with a member of the opposite sex. Zero to three?”

“That’s a bad question,” I said. “I mean, what if I was gay or bi? I’m not, but what if?”

“Excellent point, Jessica. Let’s say, then, a member of the sex to which you are attracted.”

Pause. A quick flash to Juan. “Is there a four?”

She scribbled on the paper. “Zero to three: how much you avoid that situation.”

“Normally, boys avoid me,” I joked, but her eyes stayed focus on the test. “Three.”

“Next, attending a party or other social gathering with people you don’t know very well.”

“I’m sorry, but is there a ‘does not apply’ choice?” I said. “I haven’t been to a party here.”

“I guess, imagine if that would happen, what your stress level would be. Zero to three.”

“Three.” I had figured I’d give the avoidance items lots of twos and threes, when I’d looked over the test on my own. Except it was weird to think about whether I avoid social things. Usually it just seemed like a social life avoided me.

As we went through the rest of the test, I answered threes to most of the items on school situations. After what happened in language arts, there was no pretending how I felt about “presenting in front of a small group or in a classroom setting.” What about participating in class discussions? Or joining a class or social group once the class or activity was already underway?

Most of the items about body image stuff—changing in a locker room, showering in a common shower—weren’t a big deal for me. I guess because that part of me, save being biracial with nightmare hair, was pretty normal. I hate my body clothed, and I hate my body naked. I’m pretty average.

I gave twos for speaking with strangers and authority figures, but then I kicked back to “Why aren’t there fives?” on items like eating in public, going to a party, and asking someone out. Adults didn’t bother me; I guess there’s a reason they call it peer pressure.

Nina Martin asked what my three biggest stressors were. I didn’t even have to pause before I blurted them out: speaking in class, talking to a cute guy, and going to a party. The holy trinity of terror.

“Now, we’ll finish with the distress quotient,” she said way too calmly. “Same idea. Zero to three on how strongly you react to each of these items in most social situations. Ready? Item one: feeling embarrassed or humiliated.”

“Three,” I said, “and I’ll save us some time. Three to the first eight items, down to ‘sweating.’ Give me a big three on all of them.”

She eyed me carefully. “So you know the test?” she asked with an edge in her tone. “Okay, then the final three items?”

“Zero. I don’t feel the need to run to use bathroom, and I don’t shake or tremble,” I said. But, I thought, your stupid scale doesn’t ask about the reaction I know best: crying uncontrollably.

7

BLACK WHITE BROWN, NEW IN TOWN

I stared down at the piece of paper in front of me. My first six-word memoir had earned the first F of my school career.

“Jessica, do you know why I failed you?” Mrs. Howard-Hernandez asked. I gave a small head shake. I sat with her, Mrs. Baker, the school principal, and Mr. Aaron, an educational assistant, around a small table in a conference room. This was my first “check-in,” which I’d overheard other students talking about. It seemed more like three hanging judges and one defendant.

“Your scores from junior high, last year at Verdant Hill, and on your placement tests were excellent,” Mrs. Baker said. “And on much of your work so far here at Rondo, you’ve excelled.”

“But you didn’t fulfill the terms of th

e assignment,” Mrs. Howard-Hernandez said.

“Did you fail Tonisha too?” I asked in a little-bird voice.

“I can’t tell you what grade I gave another student,” she countered. “This isn’t about Tonisha. All you needed to do was to stand up and say six words in front of the class.”

Mrs. Howard-Hernandez pointed at the paper in my hand. It was my assignment: ten six-word memoirs. My name was in black type at top of the page, along with a big red handwritten F. “Which of these would you have read in front of the class? Which is the best one? Which best describes you?”

I pointed at the last one.

“Can you read it to us?”

I took a breath. “Black, white, brown, new in town.” Mr. Aaron applauded.

“Jessica, that’s very good,” Mrs. Baker said. “So from now on, can we count on you to participate more?” Like it was that simple.

“I don’t like to talk in class. What’s the big deal?” I fought back.

“Rondo isn’t just another school; we’re a community of learners,” Mrs. Baker said. “We believe students learn best not just from teachers, but from other students.”

I hid my mouth. All my classes had way too much group work, which to me was any group work. Most of the time I got in groups with Tonisha. She took over the discussion, which was fine by me.

“Maybe you’re not challenged enough,” Mrs. Baker continued. “Many students come to Rondo because they’re behind in earning credits, but you skipped a grade in elementary school.”

Was that the start of it? Was skipping fourth grade when we moved the beginning of my fall?

“Since your scores in math and science have always been excellent, we’ve decided—if you and your parents agree—to jump you ahead to eleventh grade in both math and science.”

More strangers and cliques, my head screamed, but Juan was in eleventh grade. “Okay.”

“In your other classes, we’ll keep you in tenth,” Mrs. Baker continued. “This will also expose you to more students here at Rondo, which might help you in other ways.”

I didn’t need to ask what that meant. It meant they’d noticed I was a loner oddball.

“What about this F?” I asked Mrs. Howard-Hernandez. She motioned for the paper.

“I’ll change this to an incomplete,” she said. “You need to finish the assignment.”

I handed the paper back to her. She crossed out the F and returned it to me. “Look, Jessica, I taught debate at my last high school, so I know that many students don’t like to—”

“I don’t want to do it,” I said, fighting back tears. “But I won’t fail anything.”

No one laughed at the irony—that I failed at just about everything except most schoolwork.

“Here’s one other thing to consider,” Mr. Aaron said in his normal upbeat tone. I wasn’t fooled. “I’ve noticed in SSR that a number of students, including you, read Japanese comics.”

“Manga.”

“I’m putting together a lunchtime manga club,” he said. “Would you like to join it?”

8

IF ONLY LIFE COULD BE EASY

After dinner, the set-in-stone Johnson routine began. Mom cleared the table a dish at a time, turning a five-minute task into an hour-long project. She’d slowly wash each dish, glass, and piece of silverware by hand, not trusting the dishwasher Dad had bought a few years ago. (“What if it floods the house? What if it misses a spot?”) At the same time, she coated each dish with a thin layer of smoke, sometimes going through half a pack in an hour. By the time she finished the first smoke or dish, Dad would be downstairs on the computer, doing whatever it is he always did. I’d given up asking.

“I’m taking Maurice for a walk,” I said into the void. The word walk triggered Maurice’s animal excitement, just like group triggered my human flight response.

As I put the leash on my best friend, I glanced at the three family photos over the mantel of the fireplace (sealed off to ease Mom’s fear of a spontaneous fire starting, of course). The first picture was my parents’ wedding photo: Mom looked excited, while Dad looked maybe slightly happier than his usual look of indifference. The second starred me as a baby in Dad’s arms, Mom by his side, with their expressions reversed from the first photo—except she didn’t look indifferent so much as scared. Finally, the photo of my first day at school, where we’re all on the same page: worried. Those were the only photos up in the house, like nothing else ever happened to us.

I waited to light up until I got to the park about a half mile from our house. My parents probably knew, but Mom lacked moral authority on this issue, and Dad lacked, well, everything. He wasn’t a bad parent, he just wasn’t much of one. He provided, and for him, that seemed enough.

Once in the park, I made a beeline for the swings. With the long pink leash in my right hand and a cigarette in my left, I swung back and forth, feeling lighter than air. If only life could be this easy. But life was hard, and I made it harder. As I leaped off the swing, I knew what I needed: a time machine.

After I finished the smoke, I pulled out my phone. Mrs. Baker was right about my math skills, in part because I had a good memory. Could I recall the number I’d erased in a crying fit?

“Tim, it’s Jessica Johnson,” I said, probably sounding startled that he picked up.

In the long pause that followed, my stomach turned over and over.

“Sorry, I shouldn’t have called,” I said, and I started to hang up. I shouldn’t have dialed his number.

“Jessica, hey! Sorry, I was in the middle of eating,” he finally replied. “How are you?”

A thousand thoughts raced through my mind. Usually, when I knew I’d have to talk with someone, I’d make notes and think out every possible question and answer, except with Tim.

“Okay,” I lied, because the truth was a mess. “How is Verdant Hill?”

Tim, as always, took over the conversation. Verdant Hill was this expensive and well-regarded private school, but it was full of bullies and backstabbing cliques. There he’d excelled, as I had failed, in all things from band to theater to making friends. Why did he need more friends? He had me. As a friend, although I wished it could’ve been more. “Jessica, wow, but I think we should just be friends,” he’d said.

“You doing any better with …” he started. In my Verdant Hill days, we didn’t know I had social anxiety disorder. I thought I was just sad. Tim, who I’d met in band, made me laugh despite it all.

Now it was my turn for a long pause. I looked at Maurice. What would Dog do?

“Jessica, you there?” he asked, loudly. “Sorry, we’re out at Green Mill. It’s a zoo.”

I pictured the scene I’d always imagined: him and me, out together with a group of friends at Green Mill or some other restaurant, at a table in the center of the room. But it wasn’t to be.

“That’s okay. No … it’s not much better.” I began cataloging my Rondo mistakes over the phone. I ended up telling him about Mr. Aaron’s manga club offer. “What do you think I should do?”

“It sounds like the perfect thing. You should go for it. Trust your heart.” I agreed, and we hung up. But I thought he shouldn’t be saying anything about my heart, since he’d broken it.

9

A LOUD THUD THAT SEEMED TO ECHO

“Who is that?” I heard some girl whisper when I entered the room.

Timing was everything. Never be late to class, since that meant having to walk by every set of staring eyes. But being first to class was just as bad. It allowed each person to look you over as they came in the door. Actually, first was worse, because as each person came in, they saw you alone. And people rarely came in alone, so groups of people saw you by yourself. I thought I’d shown up in eleventh-grade science right on time. Wrong again.

Most people were in their groups, but a couple people sat alone, earbuds in, eyes down. Some looked asleep, while others were rowdy. I’d seen all these juniors around school, but I only cared about one. And Juan wa

sn’t here yet.

“Hey, new girl, what’s your name?” a girl with dark skin yelled across the room.

“Jessica.”

For some reason, this drew giggles from the girl and her friends. Most of them, like the speaker, rocked the hood look hard.

“What kind of name is that for a sister?” the same girl asked. My name and light skin sometimes confused white people, but black people saw my hair and they knew. I just turned up my music, looked for an open seat, and willed the clock to move faster.

“Hey, Miss Mulatto, I’m talking to you!”

I stopped. Even louder music couldn’t drown out how offensive that word was. I turned and started to leave.

“Jasmine, back off,” I heard some girl say from behind me.

“Wanna make me?” the loud girl, Jasmine, countered.

Then the two girls stared at each other like each was daring the other to fight.

“Have a seat,” came an adult voice—Mr. Hunter, the teacher. Everybody scampered back to their chairs. I’d been distracted and hadn’t planned an escape route.

“Sit with us,” said a cute, curvy Latina girl. There were several empty seats around the room.

“We got a spot,” came another voice, a girl from the back of the room.

I was all deer-in-headlights, standing in the middle of the room with every eye on my blushing face, my sweating pits, my metal-mouth, and my hideous clothes.

“Miss Johnson, have a seat, please,” Mr. Hunter said, and I froze.

He repeated his request, not quite as nicely. The room started buzzing like an angry beehive.

“Over here,” someone shouted to laugher. Then every class clown asked me to sit next to them. One guy pointed at his lap, another held up a chair and offered it to me. I stayed frozen like ice.

“As soon as Miss Johnson sits, we can start.” More buzzing, some in Spanish.

The door behind me opened. I wondered if it would be the principal and the people from the crazy house coming for me.

Head Kick (The Dojo)

Head Kick (The Dojo) Duty or Desire

Duty or Desire Returning to Normal (Locked Out)

Returning to Normal (Locked Out) Things Change

Things Change Controlled

Controlled Friend or Foe

Friend or Foe Stolen Car

Stolen Car Heart or Mind

Heart or Mind The Franchise

The Franchise Triangle Choke (The Dojo)

Triangle Choke (The Dojo) #1 Out of the Tunnel

#1 Out of the Tunnel Chasing Tail Lights

Chasing Tail Lights Nailed

Nailed Combat Zone

Combat Zone Outburst

Outburst Barrier

Barrier Fight or Flee

Fight or Flee Doing Right (Locked Out)

Doing Right (Locked Out) Cheated

Cheated Guarding Secrets (Locked Out)

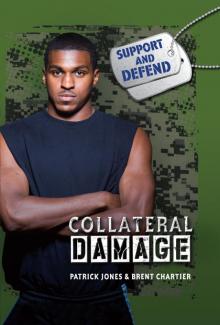

Guarding Secrets (Locked Out) Collateral Damage

Collateral Damage On Guard

On Guard Always Faithful

Always Faithful The Gamble (Bareknuckle)

The Gamble (Bareknuckle) Side Control (The Dojo)

Side Control (The Dojo) Bridge

Bridge Body Shot (The Dojo)

Body Shot (The Dojo) The Tear Collector

The Tear Collector Slammed

Slammed Drift

Drift Pass It Forward

Pass It Forward Target

Target Freedom Flight

Freedom Flight Taking Sides (Locked Out)

Taking Sides (Locked Out)