- Home

- Patrick Jones

Always Faithful Page 2

Always Faithful Read online

Page 2

8

MAY 27 / WEDNESDAY MORNING

“Rosalita, wake up,” Miguel whispers. “You’re supposed to be studying.”

I ignore him and let my face press against my open biology textbook.

“Miss Alvirde,” Mr. Richards says. Like parents with the middle name, when a teacher drops the miss or mister bomb, it’s not a good sign.

“Leave me alone,” I hiss at Mr. Richards since I can’t talk to Dad.

Dad was still up when I came home after an hour of walking circles with no shoes in our neighborhood near the Camp Pendleton base. I didn’t call Miguel or a friend. I couldn’t hear Mr. ROTC Miguel say that he agreed with my dad. And since we’d started dating, I hadn’t kept up with my friends. This was too heavy to restart a friendship with. I just walked in circles until my feet bled red into my white socks. When Dad tried to talk to me, I said, “You’re leaving me again.”

“Miss Alvirde, you need to wake up or I’ll send you to the office.” Strict tone.

“No,” I say. I put my head back on my book. He gives me another chance, but I just re-enlist sarcasm. “Actually, I’m conducting an experiment to see if osmosis really works.”

Nobody laughs, not even Miguel. Typical. Richards calls Security to take me to the office since I have no intention of leaving this chair. When the security officer arrives, I stand up. The guy’s wearing a uniform. I hate it. I hate uniforms. He says something smart and I lunge at him.

“Rosie, no!” Miguel jumps from his seat and grabs me before I hit Mr. Uniform.

The room explodes in noise. This scene—a student trying to hit Security or a teacher—is an everyday thing at my school, except that that student usually isn’t honor roll member Rosalita Alvirde.

“I hope you can get yourself together, Miss Alvirde,” Mr. Richards says, the sternness is gone and there’s an actual thin reed of caring and concern. “Now, class, about your final.”

Miguel’s still holding onto me, whispering in my ear. “Chill, Rosie, chill.”

“Can you help me, son?” the security officer asks Miguel.

Miguel nods. And in that nod, standing next to the guy in uniform, I see Miguel after two years at Parris Island. I hate him, too.

9

MAY 29 / FRIDAY MORNING

“Rosalita, I’m very disappointed in you,” Mr. Torrez, King of the Obvious, says. After serving a one-day in-school suspension, I’m allowed back in class but only after a “check-in.”

He’s right, but I’m silent. Agreeing with any Marine, active or former, isn’t on my list.

“I spoke with your father,” he says, which is more than I’ve done. Dad is a black hole.

“So,” is the two-letter word I say; FU are the two letters on the tip of my tongue.

“He told me of his decision to rejoin the Corps. He says you’re upset.” All hail the King!

“No.”

“You seem like you’re upset,” he says to me, the girl wearing baggy unwashed clothes, no makeup, her hair a crow’s nest, her arms across her chest, and biting her bottom lip raw.

“I’m not upset.” King of the Obvious, please meet the Queen of Denial.

He reaches into his desk. “I know you attended support groups before,” he natters on. “The Corps’ outreach to families is top-notch, much stronger than when you were younger.”

“So am I.”

“What?”

“Stronger,” I say. “So I don’t need you or your support groups. I don’t need anything.”

Torrez rises from his desk. If he puts that tattooed Semper Fi arm on my shoulder, I’ll bite it. “Rosie, the school is here for you. I’m here for you. The Corps is here for you. The . . .”

I cut him off. “But he’s not. My dad, he’s not here for me, is he, Mr. Torrez? Is he?”

Torrez shakes his head. “Your dad’s part of something bigger than a family. The Corps . . .”

I stand, kick the chair out behind me. “I don’t need another list. Can I go to class?”

“Rosie, I want you to see someone about getting your anger under control.”

I exit with a whisper stream of Spanish profanity. I slam the door; unfortunately, the glass holds.

10

MAY 29 / FRIDAY EVENING

“Rosie, come out of your room and talk to your father,” Mom implores me. I check the door to make sure it’s locked, which is against Dad’s rules, but it’s not like I care anymore.

“Unlock the door and at least talk with me. I’m worried about you.”

“If you want to talk with someone, talk with Dad and tell him not to go away again.”

“Rosie, it’s too late.” Her voice is hoarse again, from crying, not yelling, I assume. “He’s already signed the papers. He’s just got to—”

I slam my open palm against the door. “I don’t care. You talked him into resigning. Why couldn’t you talk him into staying home with us?” I wait for an answer, but none comes.

“Answer me!” Two more palm blows, but the pain and silence just grow deeper. “Fine.”

“Rosalita, open this door!” The cavalry has arrived, or the Marine version of it. “I’m sorry, but I’ve made my decision. You’re seventeen, almost an adult. I expect you to behave like one.”

Dad said his vows to mom, to the Corps, and I make a vow, too. I refuse to speak to him.

“I didn’t come to this decision lightly,” he says and he starts explaining his reasons again, like somehow the tenth time he does it, I’ll suddenly accept it.

“Rosie, listen . . .” Mom starts, but Dad tells her to be quiet. They’re at it again in English and Spanish. I hear Mom threaten Dad: if he deploys again, she’ll leave him, take us kids away.

“That worked once, Jaclyn. It won’t work again,” he says. “Now, Rosie open this door!”

I check once more that it’s locked. I pull Lucinda’s bed in front of the door—she’s at Grandma Rita’s place—then pile other furniture on top. Dad alternates between pulling on the knob and pounding on the door. I gather a few things and open the bedroom window.

I throw my bag down on the grass and leap to the tall oak by the house. By the time he breaks through the barricade, I’ll be gone. He’s rejoining the Corps; I’m deserting my unit.

11

JUNE 1 / MONDAY MORNING

When I get to my locker, Miguel’s waiting. I guess I knew I couldn’t avoid him forever.

“I’m staying at Grandma Rita’s for a while,” I tell Miguel before he can say anything. I don’t say I’m sleeping there because that’s a lie: I can’t sleep or eat. I can barely breathe.

“I’m worried about you, Rosie.” He caresses my cheek. “What’s wrong?”

Here goes. “My dad’s re-enlisting in the Marines and he’s—”

“I know. He told me. When you wouldn’t return my calls or texts, I contacted your family,” Miguel, the traitor, interrupts. “You should be proud of him, Rosie, serving his country—”

I push Miguel away. “I’m not proud of him! I’m so angry at him, I want to kill him!”

Miguel gets this odd look on his face, like he’s embarrassed. We’re fighting in public, but that happens all the time at this school. Except not to ROTC captains and honor rollers. The bell rings for class. Miguel puts his hand out, like I’m supposed to grab it, follow him. Obey.

“Come on, Rosie, we need to get to class. It’s finals,” he says. I don’t move an inch. He stares at me, more hurt than angry; I stare at him in the opposite proportion. He checks his phone, sighs, and runs off toward class. I stand by my locker and wait for the second bell. It goes off, louder than I remember since I’m never in the hallway for it. Always on time Rosie.

I close my locker. Down the hallway, teachers close doors to give their finals. I grab my bag and walk slowly toward Mr. Richards’ classroom. I keep walking until I get to the end of the hallway in the west wing. If Dad won’t listen to my words, maybe he will listen to my actions.

When I open t

he exit door, the alarm screams. I cover my ears and race through the school parking lot. Once out on the street, I look for the closest bus stop. It’s not that far.

“Do buses stop here any time soon?”

An older woman sitting on the bench nods and smiles at me. “Where are you going, honey?”

I pull change from my pocket. Count out a dollar fifty. “It depends which bus I get on.”

12

JUNE 5 / FRIDAY MORNING

“You flunked all of your finals!” Dad shouts at me. I’m with him, Mom, and Mr. Torrez, which is way too many Marines in an office this small.

After I bailed on Monday, I knew I couldn’t run away without getting into tons of trouble. Grandma Rita told Lucinda and me that we had to go home. With no place and no one else—Miguel and I are not talking and presumed broken up—I returned home, angry and silent.

“There has to be some mistake,” Mom says. “Rosie’s always done so well in school.”

I want to tell her there’s no mistake. On the multiple-choice tests, I picked random answers as quickly as possible, then took the rest of the time napping at my desk. On the short answers, I wrote nothing that made any sense. On essay questions, I wrote even more nonsense.

“This means she’ll need to attend summer school,” Mr. Torrez says, like I’m not there. Now that I’m a failure, Mr. Marine Torrez won’t speak my name. I’m just a “she” all of a sudden.

Finally I speak so they’ll know I’m alive and kicking. “I’m not doing summer school.”

“Then you’ll repeat eleventh grade,” Torrez fires back, machine gun fast.

“She will attend summer school. Mark my words,” Dad says with a dagger stare at me.

“What if I don’t?” I ask the three-judge panel. They look at me like I’m a space alien.

Dad’s angry, Mom’s hurt, and Mr. Torrez looks like he’d rather be anyplace but here, even Iraq. “Then you’re a truant and could be arrested. Is that what you want, Rosie?” Mr. Torrez asks.

“If I go to juvie, then I’d get to wear a nice uniform like you two.”

Mom starts to cry.

“Look what you’ve done to your mother!” Dad shouts.

“What I’ve done?” I start, and then maybe it’s the small room, the idea of summer school, the Marine tag-team, but I finally let loose all my anger at Dad for rejoining.

He answers exactly how I would. He turns, exits, and slams the door. He’s stronger than me, so this time, the glass breaks.

13

JUNE 10 / WEDNESDAY MORNING

“Rosie Alvirde?” A short black woman behind her desk calls my name.

“Here,” I mumble. It’s how everyone else answered, so I want to fit in. But as I glance around the room, I realize that’s impossible. They’re the kind of kids I’ve always avoided, but now I’m going to spend the summer with them. I don’t think I’m better. I just want to avoid trouble, which most of them find—like Miguel’s brother Alejandro and his cousin Tino.

“This is eleventh grade chemistry. My name is Mrs. Jackson,” she starts and I’m bored already.

“Whatcha doing here?” A girl whispers from behind me. It’s Brooke, Tino’s ditzy prom date.

I don’t respond because I don’t like the answer. “Well, Brooke, I deliberately failed my finals because I was angry at my dad for rejoining the Marine Corps and leaving us. What? How did that hurt anyone but me? Well, funny thing about that, it didn’t. So here I am.”

“How’s Tino?” I ask to change the subject. Jackson’s still on a monotone roll.

“My boo’s a’right.”

I try not to roll my eyes at another white girl trying to sound black. “You still hooking up with Miguel?”

She assumes that since she’s seventeen and having sex, I am too. “Maybe.”

“I’d heard you was on the outs,” says Brooke, who knows and talks too much. “We should get together—” Brooke starts but stops when Mrs. Jackson calls her out.

Brooke shuts up, but when Jackson starts talking about what we’re going to learn—stuff I already know that Mr. Richards taught a hundred times better than this robo-teacher—I’d rather listen to Brooke. But mostly I want to talk to Miguel and see where we stand.

I ignore Jackson and glance around the room: battle scars, colors, and tattoos. It sounds like the start of an unfunny riddle: what’s the difference between a Marine and a gang member? Answer: None. They’re loyal to each other over all else, even their own flesh and blood.

14

JUNE 11 / THURSDAY EARLY EVENING

“We need to talk.” Miguel’s outside my front door. I left him no choice but to come over by refusing to return calls, texts, and chats. Deep down, I know I need him more than ever now, but I just don’t know how to even explain what I’m feeling. And I’m afraid he won’t understand.

“This won’t take long.” I block the door as best I can. He’s got a hand behind his back. If it was Tino, I’d suspect a 9mm but instead Miguel pulls out a bouquet of a dozen flowers.

“I don’t know what I said or what I did, but . . .” he starts. I open the door and I take the flowers, but I don’t let him inside. I smell them, anything to avoid making eye contact. They can go on the grave of our relationship. Born in January, died in June. Cause of death, Rosie’s father.

“I’m sorry,” Miguel says, his voice as soft as his eyes. “I guess I should’ve known you were upset about your dad. I took his side. That was wrong. I’m sorry and I want you to know I—”

“You can leave.” I stare at his shoes, beat up red All-Stars. In two years, they’ll be boots shined so bright that the commandant at Parris Island will be able to see his face in them.

He reaches for me. I back away like he’s a leper, even if I’m the disease. “Please, Rosie, there’s got to be something. Tino said you were in summer school. What’s going on?”

The last time I lashed out—at Mom, Dad, and Mr. Torrez—it didn’t make me feel any better, and it made them all feel worse, so I want to save Miguel. “Miguel, you need to go,” I say.

“No, Rosie, not until you tell me why.” He tries to push his foot in the door. I stomp it.

“You need to go now,” I hiss. “If you try to get into this house or don’t leave, I’ll call the police, which is probably fine with you since you like men in uniform. Leave, now.”

“I don’t know what I can say that will make you less angry at me,” he says, but in my head I hear Dad’s voice saying the same thing. I should live in Echo Park.

“Miguel, leave.” He obeys without complaint this time. He’ll make a fine Marine. I wait until he’s at the curb before I throw his flowers and our future in the trash.

15

JUNE 11 / THURSDAY LATE EVENING

“Rosie, where are you going at this hour?” Mom asks as I head for the front door at eleven o’clock. “You have school tomorrow and there’s a curfew. Get back into your room.”

I use my new favorite word. “No.”

“When I tell your father—”

“And where is he?” Dad’s never here, which is fine. He’s at the gym getting in shape or hanging with his vet friends, getting them to join him in another stint. Five to ten, like Alejandro.

“He’s helping Victor,” she says. I mimic someone drinking and then staggering. “If you must know, he’s taking him to AA,” Mom sighs. “Victor hasn’t had a beer since he re-upped.”

“Good for Victor,” I snap. “Maybe I’ll have one for him!”

“Rosie, you get back in!” is about all I hear before my feet hit the sidewalk in front of our house. I pull out my phone, see what the rest of the world is doing, and head out to nowhere.

***

“I’ll need to see an ID,” the SDPD white-skinned, blue-eyed young cop says. I got brown hands in my pocket, white hoodie on my head, black buds in my ears, but no ID I’ll show him.

“How old are you?” he asks. I don’t answer, but I know I look my age, maybe younger.

“Curfew is 10 p.m.” I look at my phone. It’s almost 1 a.m. There’s a bunch of missed calls, texts, and messages. If only I cared about any of those people. “I’ll take you home.”

“I don’t have a home.”

“Fine, then we’ll get you a placement in a shelter for tonight,” he says. “Do your parents know where you are? Is there an adult that we can contact to let them know you’re safe?”

“You ask a lot of questions; you must be stupid,” are the last words I say before he slaps handcuffs on me. He takes my ID from my back pocket. “Rosalita Alvirde, you’re under arrest.”

16

JUNE 12 / FRIDAY MORNING

“Rosie, what are we going to do with you?” Mom says. The police guy lied—big surprise, a guy in a uniform breaking a promise to me—and didn’t take me to juvie. Instead, he just brought me home. Mom and Dad’s response was as predicted: yelling followed by shouting.

“What kind of example are you setting for Lucinda and Chavo?” Dad asks.

“What kind of example are you setting for Lucinda and Chavo?” I mock him.

“I am setting an example of a man doing what is best for his country and his family, even if ungrateful members of that family act like spoiled babies rather than mature young people.”

I mock him now by bawling like a baby. “That’s enough,” Dad commands. I continue.

“Rosie, please stop it, you’re upsetting—” I turn around. Lucinda and Chavo stand by the kitchen door, still in their pj’s. “Lucinda, Chavo, please go back to your rooms,” Mom says.

Dad rises from the table and paces like a caged tiger. He takes a deep breath and then walks toward me. He puts his arms on both sides of me; now I’m in the cage. “Rosalita Maria Alvirde, this is the last time we are having this conversation. I am sorry that my decision has angered you. Life doesn’t always work out the way we have it planned. I am making the best decision I can. When I am a Marine, I matter. I mean something, not like how I am now.”

Head Kick (The Dojo)

Head Kick (The Dojo) Duty or Desire

Duty or Desire Returning to Normal (Locked Out)

Returning to Normal (Locked Out) Things Change

Things Change Controlled

Controlled Friend or Foe

Friend or Foe Stolen Car

Stolen Car Heart or Mind

Heart or Mind The Franchise

The Franchise Triangle Choke (The Dojo)

Triangle Choke (The Dojo) #1 Out of the Tunnel

#1 Out of the Tunnel Chasing Tail Lights

Chasing Tail Lights Nailed

Nailed Combat Zone

Combat Zone Outburst

Outburst Barrier

Barrier Fight or Flee

Fight or Flee Doing Right (Locked Out)

Doing Right (Locked Out) Cheated

Cheated Guarding Secrets (Locked Out)

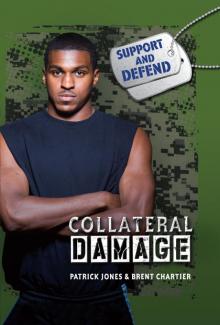

Guarding Secrets (Locked Out) Collateral Damage

Collateral Damage On Guard

On Guard Always Faithful

Always Faithful The Gamble (Bareknuckle)

The Gamble (Bareknuckle) Side Control (The Dojo)

Side Control (The Dojo) Bridge

Bridge Body Shot (The Dojo)

Body Shot (The Dojo) The Tear Collector

The Tear Collector Slammed

Slammed Drift

Drift Pass It Forward

Pass It Forward Target

Target Freedom Flight

Freedom Flight Taking Sides (Locked Out)

Taking Sides (Locked Out)