- Home

- Patrick Jones

Guarding Secrets (Locked Out) Page 2

Guarding Secrets (Locked Out) Read online

Page 2

After the bus stopped and the families stepped out, women on the other side of the doors began leaving their small cells to prepare for their visits. Most of the families headed toward the main visiting area, but Camila, her aunt, and a few others peeled off in a different direction. The new young man and his son went with Camila’s group.

“Hurry up and wait,” Aunt Maria sighed as she sat on the hard bench. Camila scarfed down the candy bar in her purse, then put the purse in a locker.

“Visitors for Gina Hernandez,” the guard said. He almost snarled her mother’s name, which Camila understood. If she worked here, she’d never smile either. Camila and her aunt walked toward the first guard station, where the paperwork was inspected. Even though he’d seen it many times, the guard—who was white, like the rest of the prison staff—took his time, asked questions, and made the long wait longer.

“You are the legal guardian of the minor child?” the guard asked in a monotone.

Aunt Maria nodded, but that wasn’t good enough for the guard. He made her say “Yes.”

Then he examined their clothing, making sure what they wore fit the many restrictions related to color, style, maybe even fashion sense. Camila wondered if kids at school would be so quick to complain about dress codes and metal detectors if they went through this routine.

“What’s in the packet?” the guard barked at Camila.

“Letters.” Camila couldn’t make eye contact.

“You can only bring in ten documents.”

“Camila, you can’t take those in,” Aunt Maria said. “I have important papers for your mother to sign. I thought I told you.”

Camila sighed and returned the packet to the locker. When she returned, she and her aunt were sent to the back of the line to start the whole process over again.

After finally passing through the gatekeeper guard’s endless interrogation, they moved to the metal detector. Even though she passed, one of the female guards patted Camila down, as usual.

A few minutes later she found herself sitting in a tiny room with her mom, her aunt, and a white correctional officer. No windows, no light. Small talk first. How are you, you look good, how’s school, how’s church, sign these papers … A guard cautiously handed Camila’s mom a pen. She signed the papers without reading them. Returned the pen without trying to stab anyone. And then …

“Are you going to be there?” Camila’s mom asked.

“There” was Folsom Prison, two hours north of here, where the California death chamber was located. “There” was where her mom would be taken in twelve days. “There,” unless another judge issued a stay of execution, her mom would be put to death.

“No, Gina,” Aunt Maria answered. “It’s a Friday. I have work, Camila has school.”

“Good.” Camila’s mother tapped her fingers on the table. “She’ll be there. Watson’s wife.” Camila knew the name as well as she knew her mother’s: Officer Chandler Watson, the man her mom had killed when she was just twenty-one.

“Have you prayed and asked for the family’s forgiveness?” Aunt Maria asked.

“Of course,” Camila’s mom said. She claimed to have found God, but not until after she had jabbed the shiv into the CO. Maybe if she’d found God earlier, Camila thought, we’d be together in a room filled with light, not in this above-ground dungeon.

“They’ll never be healed until they forgive you,” Aunt Maria said.

“Speaking of forgiveness,” said Gina. “Camila, I want to ask for yours.”

Camila stared, speechless.

“Please, Camila. Please forgive me.”

Forgive you? I don’t even know you. This was the woman who’d birthed her, who’d written her those loving letters. But she was also the woman who’d committed terrible crimes for Los Reyes.

Camila looked helplessly at Aunt Maria, and for the first time in the hour-long visit, she started to cry. Aunt Maria pulled Camila tight against her. Her mom tried to reach across the table for her, but the guard smacked his thin black baton against the table. “No PC!” he said.

Gina didn’t take the hint. Instead, she threw herself over the small table to latch onto her daughter’s hands. The CO yelled, but Gina rose, kicked the chair back, and leaned forward to smother Camila in a hug.

Camila couldn’t pull away. Didn’t want to pull away. Suddenly Gina was her mother again. Not a stranger with blood on her hands. Just her mother who loved her. Camila held her mom so tightly that her knuckles turned white as she locked her hands.

The CO grabbed Gina’s arms but couldn’t pry them apart. “Let go, now!”

Gina hung on even tighter, both crying and screaming over the CO’s yelling. A second guard entered the room and raced toward her mother.

“Camila, as long as you remember me, I’ll never die!” Gina shouted as both of the guards pulled at her mother’s arms like some game of tug-of-war. The COs locked her mom’s hands behind in her in cuffs and dragged her kicking and screaming from the room. Then there was silence, except for the words still echoing in Camila’s head: Forgive me.

6

SEPTEMBER 27 / SUNDAY / EVENING / OUTSIDE FRESNO, CALIFORNIA

Few passengers cried on the way to the prison. Almost all cried on the way home.

Camila and Aunt Maria sat in silence at first, letting their tears stream unchecked. Then Camila asked, “Is anyone from our family going to be there?”

“I doubt it.”

“I’m surprised. I thought Grandma Vickie would be in the front row.”

“Don’t talk about your grandmother that way.”

“She hates Mom. And me.”

Aunt Maria didn’t argue the point. Camila had lived with practically every member of the Hernandez family in southern California, except her grandmother, whom she’d seen only at rare family reunions. They never spoke. Her grandmother had never hugged her, always looked at her as if Camila were some foul thing.

“What were the papers you had her sign?” Camila asked.

“Legal stuff, a will, those kinds of things.”

Camila had thought about becoming a lawyer once—had dreamed of somehow finding a way to get her mom free. But now she hated it all: lawyers, judges, guards, the system.

“She asked her lawyer to stop fighting it, you know,” Aunt Maria said. “This is it.” There was a thin current of relief in her voice, and Camila didn’t blame her for it. She knew Aunt Maria didn’t want Gina dead—unlike Grandma Vickie and maybe Aunt Rosa. Maria was just tired.

“Is there anything of your mother’s that you want?” Aunt Maria asked.

Camila just shook her head. Her mother had nothing she wanted. The only thing she craved her mother couldn’t give her: she wanted her childhood back.

“She’s going to donate her organs,” Aunt Maria said. “She wants to do something good.”

“Who would want them?” Camila burst out. “They’re probably still filled with meth.” If she wanted to do something good, Camila thought, she could’ve let Officer Watson live and stayed out of prison.

Aunt Maria clasped her hand hard on Camila’s leg. “She got clean when she got pregnant with you and stayed clean for a year.”

“And then relapsed.”

“You don’t know the power of addiction, Camila.”

Camila had only vague childhood memories of her mother in a meth daze. But she had a much stronger memory of Aunt Rosa catching her coming home high one night. You’re becoming just like your mother, a worthless addict.

It was what the whole family thought, what everyone who knew about her connection to Gina Hernandez thought. Like mother, like daughter. And for a few years she’d been willing to go down that path. She’d shoplifted, tried alcohol and a few soft drugs, fought back when someone tried to beat her up. But she’d backed away from all of that after the first arrest—after Aunt Rosa had given her that newspaper article. Out of all the hundreds of articles written about Gina Hernandez, that one had been the first Camila had actually read. Every

line of newsprint was seared into her memory, deeper than any warning or insult Rosa had thrown at her.

The bus stopped at the same dimly-lit diner it always did. Camila and Aunt Maria filed off the bus with the other passengers. Inside, Camila looked at the menu and tried not to think about how soon her mom would be choosing her last meal. Tried not to think about her mom at all. As usual, she failed.

7

SEPTEMBER 28/ MONDAY / MORNING / ANAHEIM HIGH SCHOOL

“We wanna talk to you.”

The two girls from the mall stood waiting for Camila just outside advisory. She tried to walk past them into the classroom, but one of them stuck out her arm. “Are you freakin’ deaf, Camila?”

So, they knew her name. Fine. Done. “Get out of my way.”

“I’m Lisa and this is Angela,” said Lisa, the mouthier one.

“I don’t care.” What did they want from her? Everyone always wanted something.

“Look, the other day at the mall, it was weird,” added Angela, the sidekick. “We didn’t mean to hassle you.”

“Fine. Can I go now?”

“Do you do that often?” Lisa whispered. “You know, lift stuff.”

Camila didn’t answer. In her wild days back in Riverside, lifting was part of the life. Rosa told her it would land her in the same place as her mother. The one night Camila spent in juvie was enough, but every now and then, if she really needed something—not wanted, but needed something …. “Why?”

“I saw this necklace at the—” Lisa started.

“No.” Camila didn’t do favors and she didn’t need any. Favors led to connections, and connections led to questions, and questions led her no place she wanted to go.

She pushed her way past the two girls, but Lisa grabbed her arm. “Hey, no, it’s cool. I just wondered, that’s all. We asked around about you … ”

Camila’s blood froze. “And?”

“And nothing,” Angela said. “Where’d you go to school before?”

“None of your business,” Camila said.

“What is wrong with you?” Lisa shot back. “I mean, we’re trying to be nice.”

Nice—she’d met nice people before. Been betrayed by nice people before. It was never worth the risk.

“She’s freakin’ paranoid,” Angela muttered to Lisa as the bell rang. Other students pushed past the girls into the classroom.

“Girls, have a seat!” called the math teacher, Mr. Bell, but none of them moved.

“Don’t get in my business,” Camila hissed. “Or else.”

She waited. If they knew about her mom, they probably would have already said something, but this would be their last chance. Camila held her breath. Once people found out, and somehow they always did, the result was always the same. Half the people shunned her, assuming she was bad news like her mother. The other half embraced her for the very same reason. Camila wanted neither. She just wanted, more than anything, to feel normal.

“Or else what?” Lisa asked Camila. So they didn’t know. Yet.

Camila narrowed her eyes to slits and gave them the same cold glare she’d seen her mom use on guards. Without saying a word, she turned and went to her desk.

8

SEPTEMBER 28 / MONDAY / AFTERNOON / ANAHEIM HIGH SCHOOL

Juan handed his phone to Camila as soon as they sat down to eat in the cafeteria. “Check out the pictures from the quinceañera.” Camila studied the photo on the screen. In it, Juan stood with several relatives, including an older man who could have been his twin, separated by twenty years. “That’s my uncle Javier. He’s a marine. He’s my role model, along with my dad.”

“You look a lot alike,” Camila said, forcing a smile. “Both handsome.” She and Juan scrolled through the rest of the photos, but out of the corner of her eye, Camila watched for Angela and Lisa. Instead she saw something worse: a skinny kid who looked way too familiar. Camila buried her face in Juan’s shoulder to avoid being seen.

“I’m sorry I couldn’t be there,” she mumbled.

“Well, I do have two other younger sisters, so maybe the next one.”

Camila smiled, for real now. So Juan expected them to still be dating in a few more years. Most of her life she’d been shuffled from one relative to the next, never staying anywhere long enough to matter. The idea of a future that she could plan for—a future with Juan in it—made her feel older and younger, stronger and more fragile, all at once. “You’re sure that will be OK with your parents?”

Juan put his phone down on the table. “Look, Camila, don’t worry about that. It’s not that they have anything against you personally. It’s just that my dad tends to think the worst about everybody our age, especially people who live in your neighborhood.”

“Where you come from doesn’t make you a certain way.” Even as the words left her lips, she wanted to take them back. She wondered if she’d just lied to earnest and honest Juan.

“I know that,” Juan said. “He does too. He’s just a tough customer. My mom too.”

And as always with Juan, or anyone Camila had gotten the least bit close to, she was at a loss for what to say next. Always fearing she’d need to answer for herself, for her family. Dad? I don’t know because my mom never knew. Mom? Meth-head, gang member, and murderer.

“Camila, I know you don’t like to get involved in school stuff,” Juan started. There was a rare nervousness in his voice. “But the homecoming dance is coming up in a few days and I was wondering if—”

“It’s not a few days, Juan, it’s a week from Friday.”

“You must have the date circled on your calendar,” Juan joked. “Does that mean—”

“No.” She did have the date circled, but not because it was homecoming. “I can’t go,” she said.

“Why not?”

“Well, for starters, I don’t have money to buy a new dress.” She paused. Juan said nothing, didn’t react at all. “But mostly, it’s just not a good time. A lot of family stuff going on, that’s all.” She flashed what she hoped was a sly grin. “Hope that’s not a deal breaker or anything.”

“You kidding me? Of course not.”

On impulse, Camila kissed Juan full on the lips, which got a reaction from people at a nearby table. She pulled back quickly. She hated calling attention to herself, especially now. The skinny kid she’d noticed a minute ago seemed to be looking around the crowded room for a place to sit.

“Good,” she said. “I figured I could count on you still liking me, dance or no dance.”

Juan pulled Camila close, burying his head against her neck, resting his lips against her right ear. “I don’t like you, Camila,” Juan whispered. “I think I love you.”

Love—that was a word she’d heard a million times, and what did she have to show for it? What was love, other than shorthand for broken promises?

She closed her eyes and held her breath so she wouldn’t admit the truth: I love you too.

9

SEPTEMBER 28 / MONDAY / LATE AFTERNOON / ANAHEIM HIGH SCHOOL

“Didn’t you used to go to Sierra Middle School?”

Camila looked up at the person standing in front of her locker. It was the skinny guy from lunch. She remembered him, not fondly, but that was true of most of her school experiences. Riverside, Corona, Long Beach, several schools in the Los Angeles district—all places she’d rather forget. Her time at Sierra had been brief for the usual reason. One family member had gotten sick of her and pawned her off on another.

“No,” she lied.

Camila closed her locker and started to walk down the hall, but he followed her. “I know you. You’re that chick whose mom—”

Camila whirled on him. “Listen, you don’t know me. Understand?”

“Nah, girl, I remember you. Killer Camila.” He grinned. A shiver snaked up Camila’s spine.

She kept walking, hoping to lose him in the end-of-the-day chaos of the hallways.

The guy darted in front of her to block her path. “What’s the big deal

? Everybody at Sierra gots somebody inside. I mean, my pop’s doing a dime at San Quentin. It ain’t nothing.”

Camila stared at the floor. It looked as if it hadn’t been waxed in years.

“Look—Steven, right?” The kid nodded. Camila wasn’t sure how she remembered his name, but was glad she did. It made this just a fraction easier. “It’s different for girls.”

“What are you talking about?”

“Think of all the people in prison. How many of them are women? And how many of them are … ” She didn’t say the last three syllables. “I mean, it was a huge deal when she got sentenced. In the news and everything. Because she’s a woman.”

“Shot a cop right in the face,” Steven said. And laughed, way too loud. “Man, I’d like to meet her. Shake her hand, thank her for that.”

Camila thought about saying, Then you’d better hurry, she’s only got eleven more days. But then again, maybe he knew that somehow. Maybe he knew everything, and maybe he’d tell everyone.

“Look, people here don’t know. I want to keep it that way.”

She skirted past him and headed for the front doors, but Steven followed her.

“So what’s the scene here?” he asked, like he was making casual conversation. “Whose turf?”

“I don’t know.”

They were almost at the front doors. Camila thought about running the rest of the way but decided not to. It might draw attention.

“What’s your problem?” Steven snapped.

Camila turned. “Just leave me alone, OK?” She fixed Steven with a hard stare, just like she’d used on Lisa and Angela.

Except Steven didn’t blink. He stared back with cold brown eyes. Hearing the buses outside revving their engines, Camila reached for the door. Steven reached forward too, but not for the door. He grabbed her right arm and pulled her sleeve up.

“What are you doing?”

Steven stared at Camila’s bare right arm. “Just wondering, you know.”

Head Kick (The Dojo)

Head Kick (The Dojo) Duty or Desire

Duty or Desire Returning to Normal (Locked Out)

Returning to Normal (Locked Out) Things Change

Things Change Controlled

Controlled Friend or Foe

Friend or Foe Stolen Car

Stolen Car Heart or Mind

Heart or Mind The Franchise

The Franchise Triangle Choke (The Dojo)

Triangle Choke (The Dojo) #1 Out of the Tunnel

#1 Out of the Tunnel Chasing Tail Lights

Chasing Tail Lights Nailed

Nailed Combat Zone

Combat Zone Outburst

Outburst Barrier

Barrier Fight or Flee

Fight or Flee Doing Right (Locked Out)

Doing Right (Locked Out) Cheated

Cheated Guarding Secrets (Locked Out)

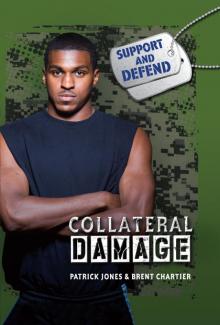

Guarding Secrets (Locked Out) Collateral Damage

Collateral Damage On Guard

On Guard Always Faithful

Always Faithful The Gamble (Bareknuckle)

The Gamble (Bareknuckle) Side Control (The Dojo)

Side Control (The Dojo) Bridge

Bridge Body Shot (The Dojo)

Body Shot (The Dojo) The Tear Collector

The Tear Collector Slammed

Slammed Drift

Drift Pass It Forward

Pass It Forward Target

Target Freedom Flight

Freedom Flight Taking Sides (Locked Out)

Taking Sides (Locked Out)