- Home

- Patrick Jones

Pass It Forward Page 2

Pass It Forward Read online

Page 2

“I heard from Rachel last night.” Grandma starts bragging on her youngest daughter’s children. “Both their sororities are doing food drives for the poor, as the Lord would want.”

Whenever Grandma mentions Mom’s sister Rachel, her husband, or her kids, Mom’s face reacts in pain like Grandma is pouring small white salt crystals into big open wounds.

“What will you do after graduation?” Grandma clicks her green-painted nails on the table.

“After our game last night,” I say, all excited, “I think I’ll be the first high school player from Alabama to succeed going straight from high school to the pros.”

Grandma points at Mom and shakes her head. “Your children and their foolish schemes.”

When I make it, I’ll be the only of Mom’s three sons to succeed. That’s a poor shooting percentage. “Mark is a criminal,” Grandma says, full of fury. “And Josh failed at even doing that.”

Mom winces in pain. Her hurt back isn’t up to the lashes from Grandma’s whip-like tongue.

“Don’t worry, Mom,” I say. “I’m gonna make it somehow. Just have some faith in me.”

Mom smiles, but Grandma clicks her nails harder on the table. “Fool-headed big dreams.”

I stand. That gets Grandma’s attention and the clicking stops. “How come you believe in Jesus, who you’ve never met, but you can’t have even a little faith in your own flesh and blood?”

9

Sunday Evening

February 12

Tuxedo Park

The ball whooshing through the net contrasts with the blaring sirens in the distance. “Li’l Mark, that was a cold shot!” Kevin shouts to me from across the dimly-lit court. I don’t disagree or tell him how I hate that he and all of Mark’s old friends I play against use that name. I’m big now. And I’m not Mark.

Kevin likes the shot even more because it wins us the game. Kevin, Tony, and Scott decide to take a break before we go again. Scott’s new to our Sunday night game. He replaced my brother Josh.

Even though it’s cold outside, Mark’s friends cool off more by drinking forty-ounce beers.

“How’d you get so good?” Scott asks as he offers me a forty. I decline.

“Playing them.” I point at Kevin and Tony. They laugh, but I’m not sure why. If they would have stayed in school and kept up their grades, they would have been scholarship material. While a college coach would’ve smoothed out their moves, their instincts for the game—like Mark’s—were so good, they could have made the NBA. Instead, they get a game at tiny Tuxedo Park.

“Does Mark even play anymore?” Scott asks.

“Not since he broke his ankle,” I answer, which for some reason makes Kevin smirk.

“Mark’s too busy with other things,” Kevin says. Kevin and Tony laugh. They’re not only Mark’s friends. They’re also part of his crew. They traded hitting jumpers for likely wearing County Jail jumpsuits. Me, I just want to wear a basketball uniform as long as I can, but that’s easier said than done. The court comes easy, yet my shot at making it is slim; the streets are hard but the payoff’s every day. Lots of risk, but lots of rewards. Mark showed me that too.

They finish their beers and we hit the court again. When Kevin makes a crazy dunk, I tease him, saying, “Great shot, Kobe.” He cracks up every time I say that. When Mark first introduced me to the park and the game, people got nicknamed according to the player they most resembled, which was normally an NBA star. Kevin would see a Kobe move on Friday, try it out on Saturday, and by Sunday have it down stone cold. I was the same, except I didn’t see the moves on TV. I saw them on the court made by my oldest brother. As much as I don’t like it, I know I’ll always be “Li’l Mark.”

We play until my curfew. Then I go home to study. They head off in another direction.

10

Monday Morning

February 13

Jackson High School

There’s crackle but no snap or pop from the rip-off Rice Krispies served in the cafeteria. I crack that to the guys on the team, who sit together every morning. Everybody laughs except Nate. Instead, he’d rather laugh at me. “Luke, you don’t need a spoon; you need a big shovel.”

Elijah cracks up at Nate putting me down. I answer by eating even faster. My guess is Nate had something other than macaroni with butter for dinner, but that’s all I know how to cook. Mom stayed in bed last night. She even called in sick to both her jobs, which she never does. Working these hard jobs, Mom’s hurt her hands, arms, legs, and feet at one time or another. Like some wounded soldier, she usually keeps pressing on, but not today. That’s how I know it’s bad.

Pretty soon everybody’s laughing at everything. It’s the sound of a winning team. That’s on me. I started the season as back-up guard, and now I’m the lead scoring forward. In our first season game, I got zero minutes. In our last playoff game, I had a triple-double. Things change.

Nate makes another crack. “Luke, your stomach’s a vacuum sucking down every—”

“Yeah, I’m a vacuum,” I say, interrupting his insult. “A vacuum that sucks down rebounds.”

“And smacks down shots,” Elijah adds. He’s our captain, our leader. Elijah’s okay. The thing about following leaders, though, is they can create a vacuum in their wake. Josh followed, and I saw where he ended up going. Down. The streets are a vacuum of their own.

I know why Nate’s upset—I took his minutes—but I don’t get why he can’t let it go. I shrug and slurp down the last of the milk and cereal as the bell rings for class. Since first period equals Mrs. Thompson’s class, I don’t want to be late. Something about her makes me not want to disappoint her by doing anything wrong. Kind of like with Mom.

The only thing louder than the bell is the noise of a hundred free-breakfast kids nourished, like me, probably for the first time in hours, burning it off and heading to class. Normally I hate the noise of the crowded hallways and would put on my beach CD, but I welcome the clatter this morning. At home, ever since she caught Mark in our apartment, silence is all I get from Mom. That is, unless you count the groans of her pain. It’s not my fault, but she’s acting like she blames me for letting Mark in the door that day. That’s a burden too large even for my broad shoulders.

11

Monday Afternoon

February 13

Jackson High School gym

Coach’s whistle screams like Mom’s old teapot. Both mean hot water.

“Elijah, you need to move the ball quicker,” Coach says. “And, Lucas, you need to fight harder to get free.” I want to say “That’s what I’ve been doing all my life,” but I say nothing.

The thing about Coach Unser is that he teaches us plays, but in games, he doesn’t get mad if we freelance. As long as we knock down two or three, he’s fine. It’s an easy system.

Mark played college ball in Tennessee. That is a basketball state, unlike Alabama. People here think basketball is something tall people do to fill time between football and baseball. Mark complained about his coach’s system limiting his freedom to play his game. Mark even blamed his coach for the broken ankle that finished his college career. The ankle never healed right, but I wonder if that’s all that stops Mark from still getting a game. He doesn’t want to remember or talk about it.

“Luke, wake up!” Elijah throws the ball at me. I catch it, take a step. Head fake even though nobody’s in front of me. I do it like I learned it. Not from Coach, but from Mark. Ball goes in. Three.

Coach tells us to start practice. I square off against Nate. He plays hard and smart and strong. Trouble is that I’m harder, smarter, and stronger than him. I grew up and got buff. He didn’t.

I don’t just shut Nate down—I give him a spanking worse than his mom ever did. If there were a score sheet for scrimmage, he’d be nothing but negatives: turnovers, fouls, and missed shots. The one time he almost beat me, I hustled back and rejected his shot with harsh intent.

After wind sprints to end practice, Nate comes over to

me. He breathes heavy. “Man, Luke, how come you had to grow four inches and put on twenty pounds of muscle over one summer? These were supposed to be my minutes. My tournament. My scholarship opportunity.”

He wants an apology he won’t get. “I guess wrong place, wrong time for me,” Nate says.

In front of me is Nate, but in my ear, I hear Josh saying those same words over and over.

12

Monday Evening

February 13

Lucas Washington’s apartment

“You are late.” Mom’s three words of disapproval deafen me. At least she’s talking to me again, but when she does, it’s all anger and pain.

“I’m sorry,” I mutter. After practice, I still wanted a game. Nobody was playing at Tuxedo, so I caught the bus to the UAB. There I got a game against college players. I lost, but I’ll call it a win since I didn’t let myself get down getting beat by guys older and better than me.

“You need to sit down and study.” Mom points at the empty chair.

“Way I remember it, Mark never studied and he still went to college. So I don’t—”

“For less than one year.” Mom slaps my face with her words. I join Mom at the kitchen table, where she’s eating Dollar Store popcorn. It doesn’t pop, just like the cafeteria breakfast cereal. It seems nothing around here lives up to the hype. Not cereal, not snacks. Not Mark, maybe not me.

“Stuff happens,” I say. Mom’s hard look somehow grows harder. “It wasn’t his—”

“Luke, don’t you have studying to do?” Mom camouflages her command as a query.

I think about Mark. He was twice as good as me on the court. Now, he won’t even play. He’s too busy making green to bother with the orange ball. “Why didn’t you take Mark’s money—at least just until you can go back to work?” The question attacks her ears, but it is her back that Mom clutches like I’d stabbed her.

“I don’t want his dirty money in my house,” Mom says. I look around the small, empty apartment. This isn’t a house or a home. It is shelter from the storm of our endless poverty.

“But—” I get in one word before Mom blocks my sentence with a “shut-up” stare. The only things hotter than Mom’s angry eyes are Mark’s hundreds burning like hellfire in my pockets.

The more Mom talks, the worse I feel. She’s trying to inspire me to be better than Mark and Josh, but her words drag me down like a weight. “My back is killing me,” Mom moans.

“It will get better,” I say, not sure if I believe it, but I know I have to stay positive—always.

13

Wednesday Morning

February 15

Jackson High School playground

The heavy weights clank as I push them up and down across my chest. They echo in the silence. Like most mornings, it is just me in the school’s old weight room. There’s no carpet on the cold floor, and the old equipment lingers with the odor of ancient sweat. I towel off and head toward the playground to catch a quick pick-up game in the half hour before school starts.

“Hey, Lucas.” It’s Trina Saunders. I say something back, but I doubt she hears it through those giant red headphones covering her ears. “You got another game tonight?”

I motion to the headphones. She removes them. “Yes.” I can’t look her in the eye. “When we win, then we go to the semi-finals, but not ’til the twenty-fourth.”

“So no game this coming Saturday?” she asks.

I shake my head no. She smiles pretty but says nothing. Saturday night is my lame school’s late Valentine’s Day dance. Maybe she wants me to ask her but wonders if I can afford it. I survey the schoolyard. Lots of other folks wear big headphones like Trina, but they also dress nice, got fancy phones, and act like they got money. I bet they do. I know a lot of them didn’t earn it working a crappy job a long bus ride away, like us. They earned it standing on a corner.

“I hope you win.”

“You don’t need hope when you’re as good as us.” She laughs as pretty as she smiles.

I feel the empty space in my pocket where one of Mark’s hundreds once was. I gave it to Mom but told her it was from work. She didn’t question it. She used it to help pay the rent, I hope.

Trina stares down at the pavement below. “There’s a school dance on Saturday night.”

It feels like I’m still sweating from the weight room. “I know.”

Then we fall silent as everyone rushes around us, their loud voices filling the air. It seems like people try to get all their yelling and laughing out before they go inside, except it doesn’t work. “I probably have to work anyway,” Trina finally says. She turns her back and walks away. I don’t say anything.

14

Wednesday Afternoon

February 15

Jackson High School

The Bunsen burner whooshes in the science lab when I turn it on. Elijah is my lab partner. He’s as jokey off the court as he is serious on it. Mrs. Thompson tells him to knock it off. And he does. She’s always calling him out. She never notices me, as if I’m invisible. Fine with me.

“So I was going to ask Trina to the dance,” I whisper. “But . . .”

“She has a fine one of those for sure.” I bite my lip so I don’t laugh. “So why not?”

Elijah’s a great point guard who feeds me the ball when and where I want it. I guess I owe him the truth. Or half of it. “It’s about money.” He nods. He knows this life too.

The other half of the truth is, as much as I’d like to go out with Trina, I also know Mom had two kids before she was eighteen, just like her mother. More mouths, less money. I know things happen that can make things get real fast, and I refuse to follow in those footsteps.

I turn my attention to the experiment, concentrating hard since Elijah’s acting goofy.

“That’s a good job, Lucas,” Mrs. Thompson says. Elijah giggles. Why is she busting me?

She notices the embarrassed expression on my face. “No, Lucas, I’m serious. Excellent!”

This is the first time I can remember any teacher, except a coach or P.E. guy, telling me I was doing something right. “Could you explain to the class what you are doing, Lucas?”

I stand up, and everybody else is sitting so I feel like a hulking monster. I start to explain, but I stumble over my words. I hate talking in front of the class. I’m relieved when Elijah takes over for the save.

After he’s done, Mrs. Thompson says, “Well, thank you, Elijah. Perhaps when Lucas becomes a scientist or doctor, you could be his spokesperson.” Everybody cracks up at that.

I stare into the blue flame like it was a crystal ball. If I don’t make the NBA, I could go to college and study for one of those jobs—except for one thing. College costs money. Maybe that’s why money is green. It means “go.” If you haven’t got it, you’re stuck.

15

Wednesday Evening

February 15

Lee High School gym

Game 3

The swoosh of the ball through the net sounds like the collective sigh from the hometown Lee crowd when I sink two more free throws. I’ve got almost as many points from the line as from the lanes. They’ve double-teamed me all night, trying to stop another double-double. Instead the Lee hacks have fouled me or left another Mustang free to shoot, mostly Paul tossing up hooks.

“Nice job!” Jeremy says to Paul with a wide smile. Paul earned it, passing the ball with speed and vision. Even though there’s only a minute left, Coach leaves in the starters. Not to pile up the score, although we’re doing that, but because Coach knows recruiters attend tournament games.

Lee inbounds, but their point guard plays sloppy and Elijah steals the ball. Rather than racing for the basket, he slows up and surveys the court. I race toward the baseline and break my double-team. I flip my thumb in the air, calling the play that I saw Mark do a hundred times.

Elijah nods and dribbles, almost acting bored. He sets to shoot. I drive toward the basket. Elijah hurls the ball high toward the net—n

ot a shot, but a pass. In one motion, I snatch the ball and stuff it in the basket. I pretend I can hear recruiters scribbling my name in their notebooks.

I would’ve thought that since we’re in Huntsville, home of rocket scientists and their offspring, their team would play a smart game. School smarts doesn’t always equal court intelligence. The only way I will get a scholarship is through basketball, but only to a school that doesn’t have high academic standards.

After the alley-oop, Coach pulls me. “Great game, Lucas, but that’s enough for tonight. We’ve got to save some for the semi-finals.” I get a pat on my sweaty back from Coach.

“I don’t know how to save anything,” I say as I grab some pine.

Truth is, I have saved one thing. I’ve saved myself from walking in both of my brothers’ footsteps, even if I do wear Mark’s hand-me-down Chuck knock-offs. Mark only wears Versace now. But even my cheap sneaks are better than whatever footwear County makes Josh wear.

16

Saturday Morning

February 18

Ryan’s Steak Buffet

Mark’s laughter booms over the din of late-morning diners at Ryan’s. When I hear Mark from a few tables away, I duck behind a table like I’m picking something off the floor, hoping he doesn’t see me.

“Can I get some shrimp or what?” Mark yells out. It is ten o’clock in the morning. Mr. Robbins furls his thin brow and waddles his fat body in Mark’s direction. He’ll need reinforcements. It is not just Mark, but also Tony, Scott, Kevin, and four girls I don’t know.

The laughter ends and I hear, even from my long distance, some harsh words exchanged, many only four letters. “My little brother works here!” Mark shouts. “Let me talk to him.”

Rather than having Mr. Robbins find me, I stand up as straight as I can and walk over to Mark. He and his friends laugh when they see me. Maybe if I were in their dancing-all-night party shoes, I’d laugh at the sight of me as well. “Mark, we don’t put out shrimp until lunch.”

Head Kick (The Dojo)

Head Kick (The Dojo) Duty or Desire

Duty or Desire Returning to Normal (Locked Out)

Returning to Normal (Locked Out) Things Change

Things Change Controlled

Controlled Friend or Foe

Friend or Foe Stolen Car

Stolen Car Heart or Mind

Heart or Mind The Franchise

The Franchise Triangle Choke (The Dojo)

Triangle Choke (The Dojo) #1 Out of the Tunnel

#1 Out of the Tunnel Chasing Tail Lights

Chasing Tail Lights Nailed

Nailed Combat Zone

Combat Zone Outburst

Outburst Barrier

Barrier Fight or Flee

Fight or Flee Doing Right (Locked Out)

Doing Right (Locked Out) Cheated

Cheated Guarding Secrets (Locked Out)

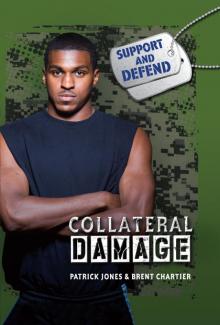

Guarding Secrets (Locked Out) Collateral Damage

Collateral Damage On Guard

On Guard Always Faithful

Always Faithful The Gamble (Bareknuckle)

The Gamble (Bareknuckle) Side Control (The Dojo)

Side Control (The Dojo) Bridge

Bridge Body Shot (The Dojo)

Body Shot (The Dojo) The Tear Collector

The Tear Collector Slammed

Slammed Drift

Drift Pass It Forward

Pass It Forward Target

Target Freedom Flight

Freedom Flight Taking Sides (Locked Out)

Taking Sides (Locked Out)