- Home

- Patrick Jones

Stolen Car Page 16

Stolen Car Read online

Page 16

“Reid and I broke up,” I tell her. “Please don’t say ‘I told you so’ or anything, just tell me one thing.”

“What’s that?”

“Just tell me you love me no matter what.”

Mom pauses, takes a deep breath. I think I hear a smoke being lit. “Of course I do, Danny. I’ll love you no matter what. That’s why I’m so worried about you.”

“I’ll be home tomorrow, maybe the next day,” I tell her. I’m not lying; I don’t know what we’re going to do. About the only thing I know is that I’ll never, ever see Reid again.

“Promise me you’ll call me again,” Mom says. “Promise me everything is all right.”

“Promise,” I tell her. “Can you do something for me?”

“Baby, what do you need?” Mom says.

“Ashley’s with me. Can you tell her parents that she’s okay?”

“Why can’t she tell them herself?” Mom asks with concern, not anger. I look over at Ashley and she’s still staring out the window, like she’s going into one of her trance-like states.

“It’s all complicated, Mom, but please, please just let them know.”

“Where are the two of you? They’ll want to know.”

I tap Ashley on the shoulder and she turns around, her eyes red. “My mom needs to know where we’re going. She has to tell your parents something.”

“Tell her to just tell them that we’re looking for someone,” Ashley says.

“Who’s that?” I ask.

She takes a deep breath, turns away from me again, and says, “My mother.”

“Your mother?” I try to get her to talk, but she just keeps staring out the window.

• • •

I’m still following the signs north, but it’s getting harder. I’m exhausted, not just from having to super-concentrate on driving, but from all the day’s events, especially Ashley’s last statement.

“I need to sleep,” I tell her as I follow the road into Tawas. “I’m pulling over.”

“No, we need to find a motel,” she says.

“I don’t think we could get a room on our own,” I confess. “Even if we could, Evan didn’t give us that much money. No, we’ll just sleep in the car.”

“No! Danielle, I won’t sleep in the car.” She’s not talking, she’s shrieking.

“But Ashley, we don’t—”

“I won’t do it,” she says, then points at a road sign. “There used to be a cheap motel just on the other side of downtown. Please, let’s just go there.”

I want to ask her how she knows about the motel. I need to ask her what she meant about looking for her mom. But mostly I want and need to sleep, while I sense Ashley needs time.

Ashley uses the little bit of makeup she has in her purse to make herself look older than her sixteen years. She goes into the motel office and returns a few minutes later with a key. I park the car near the back of the lot, which is mostly full of semitrucks. We stumble toward the room like two lost travelers through the muggy midnight air.

The place is pretty dirty, but I don’t care. I go to the bathroom first. By the time Ashley comes out, I’m lying faceup, staring at the ugly off-white cracked ceiling. It’s hard to even hear myself breathe over the loud fan of the air conditioner and the louder TV in the room next door. I try to turn the fan off, but the knob is broken. Like the town outside, this motel’s seen better times.

Ashley sits on the edge of my bed, pulling her hair away from her face and staring at me.

“I’m sorry I got us into this,” I tell her.

“It’s not your fault,” she says, then kicks off her shoes and lies down next to me.

“I should have known. Everybody told me, but …” I stop, waiting for the I-told-you-so moment, but it doesn’t come.

“Remember what I told you at the start of the summer?” she asks. I shake my head. “You can’t tell people stuff, you have to show them. Reid had to show you who he really was.”

“But I knew, I knew,” I say, trying to hold back tears.

“Knew what?”

“Knew he was too old for me. Knew he was too good-looking. Knew that—”

Ashley cuts me off, her voice sharp. “No, it’s not that. It’s not that at all.”

“Then what?”

“That he had no conscience. No guilt or sorrow,” she whispers. “I saw it in his eyes.”

“How could you know that?” I ask.

She takes a deep breath, then says, “It’s complicated. You can’t tell anyone.”

“Promise,” I say as she puts her head on my shoulder, then speaks to the ceiling.

“Those people I live with, they’re not my real parents,” Ashley starts. “They adopted me when I was eleven. Before that, I was living in foster homes with other rejects, each home worse than the last. Then Peter and Elizabeth came into my life. I did everything I could to get them to hate me, because I didn’t think I deserved any better. I didn’t just put up a fence around my heart; I loaded it with explosives and barbed wire. I almost destroyed myself.”

“Ashley, I didn’t know.”

“I didn’t want you to know that Ashley,” she explains. “I drank, did drugs, everything I hate now. I was so angry that I needed to act out. That’s what my therapist helped me recognize.”

“I understand so much now,” I reassure her, but she just waves it off.

“I’d done more shit by the time we met than any fourteen-year-old should have. But every time, the ’rents kept taking me back, trying their best, loving me. Finally I knew they were real, and that I could have a home again, and something like a normal life, even if I’ll never be normal.”

“What will you be?”

“I’ll just be Ashley.”

“Ashley, I didn’t know,” I repeat.

“I couldn’t tell you. I’m so ashamed of who I was and the things I did,” Ashley says. “I’m tired of lying to you, to myself. It’s too hard, and after everything that happened today, I knew we could really trust each other. So, I’m sorry I lied to you about so many things.”

“Like what else?”

“Well, you’ve known me for two years. For two years I’ve told you I take piano lessons, but have you ever seen me play the piano? No, I go to therapy once a week, but it’s not enough. I’m also on medication, anti-depressants, and some other stuff.”

I’m just staring. Ashley’s hair has fallen over her eyes, but that’s not her only mask.

“The therapy helps me understand. My therapist is really smart. She’s why I’m always spouting wisdom,” she says. “It’s all part of processing the pain, anger, and loss in my life.”

“But your parents seem—”

“Don’t call them my parents,” Ashley says. “I had a mother, now I have these people.”

“What about your dad?” I ask, but I only get a cold stare in return. It reminds me of the way she stared at Reid the first time she saw him, like her eyes were knives cutting into flesh.

“These people? You sound like you don’t love them, but I know you do,” I say.

“No, Danielle, I don’t love them,” she says, as icy cold as the room. “I like them most of the time. I appreciate them, and I respect them, but I don’t love them.”

“You’re just angry,” I say. There’s this new Ashley in front of me and I’m confused.

“I can’t love them,” she says. “That would be betraying my mom. Can you understand that? Like I said, it’s hard, especially since they tell me all the time how much they love me.”

“They’re not just saying that,” I tell her.

“I know, but it’s not the same,” she says, her teeth chattering. “You can’t say it, you have to show it. I came here to show my mom I still love her.”

“Do you want to call her?” I ask. “Could we stay with her tonight?”

“I’m so cold,” is Ashley’s strange non-reply.

“The fan is broken, or I can’t figure it out, I’m sorry,” I say.

> “I’m freezing!”

“Let me take another look at it.” I get out of bed, but Ashley grabs my arm.

“Danielle, can I ask you something?” She’s whispering again.

“What?”

“Will you forgive Reid?”

I don’t even need to think before I say, “No, I can’t and I won’t.” Reid was right, I wasn’t his girlfriend, but I wasn’t even a girlfriend. I was just another victim. I go to sleep to night as Danielle the Defeated. I can only hope in the morning, when Ashley reconnects with her mom, that I can share her joy—because I feel none to night.

17

THURSDAY, August 14

“Ashley, where are you?” I ask, but there’s no answer other than the sound of running water. I quickly get dressed, then find some change so I can get a Coke to help myself wake up. When I get back to the room, the water is still running.

“I’ll be in the car,” I shout through the bathroom door. I snatch the keys, then head outside to let my brain try and absorb all the intense experiences of the past few hours. I find a half-smoked cigarette under the passenger seat. It has lipstick on it; a brown shade of lipstick I don’t wear, but Angie does. I turn my phone back on. More missed calls from Mom, Evan, and Ashley’s “parents.” And one call from Reid, which I return.

“Where’s my car, bitch?” Reid shouts at me the second he answers. Before he picked up, part of me hoped against hope that the past twenty-four hours had just been a nightmare. “I said, where the fuck is my Viper?”

“How many?” I reply, holding on to the lipstick-stained cigarette.

“How many what?”

“How many other girls?” I ask. I instantly understand how my mom must feel before Carl hits her: she knows the blow is coming, but something stubborn, proud, and stupid keeps her from backing down.

“How many other girls what?” Reid snaps back.

“Did you have sex with?” Acid churns in my stomach as I ask the question.

His laughter is like a needle jabbing into my ear.

“I didn’t have sex with you, girl,” he chortles. “You just blew me.”

I lick my bitter lips but say nothing.

“And you weren’t even that good at it,” he continues. I turn another cheek. I need his contempt, disrespect, and hatred to keep me away from him forever. “Maybe I should have had Angie or somebody give you lessons. I shouldn’t have asked a girl to do a woman’s job.”

I throw the cigarette out the window, although I think about throwing it under the hood of Reid’s car, then running like hell.

“I did take lessons,” I say once he stops laughing.

“From who?”

“From Vic,” I shoot back. Then I start the car.

“So, he’s a faggot as well as a loser.” More laughter, more pain, more relief.

“No, Vic taught me how to get rid of a stolen car, one piece at a time,” I say slowly over the racing engine. “First, you need the right driving music!”

I can barely hear him shout, “Don’t touch my car, bitch” over the Viper’s mighty roar and the sound of “Highway to Hell” blasting birds out of the trees.

• • •

“Where to?” I ask Ashley when she finally emerges from the motel room.

“I think I remember,” she says, then yawns as she gets into the car.

“You’re sure you don’t want to call?”

She responds with silence, simply pointing which way I should turn.

“Where did you live?” I ask as we drive slowly through the small town. I can see how maybe once this had been a nice place to live, but now it’s filled with boarded-up stores, vacant lots, tons of houses for sale, and more pawnshops than fashion boutiques.

“Mostly here,” she says.

“No, I meant where was your house?”

Ashley leans over and taps me on the shoulder, then points to the backseat. “The last year, we mostly lived in Mom’s car. We had lived with relatives, at a shelter, but mostly I remember sleeping in the car: Mom in front, me in back, even sometimes in the freezing winter.”

I don’t say anything. Instead, I use my mathematical mind to add it up: her hatred not just of driving, but of riding in cars, plus her fit last night about needing to find a motel. I look over at Ashley. I’ve seen or spoken to her almost every day for nearly two years—I’ve called her my best friend almost as long as I’ve known her. But I understand now that I’ll never really know her, because the life she’s telling me about is one I can’t begin to imagine living. Most of my life I’ve been poor, living in dumpy trailer parks, but Ashley’s lived like a refugee.

“It’s around here someplace,” she says after we pull off one of the main roads. The open windows suck in the humid August air, but Ashley looks like she’s shivering again, with a coldness in her bones from her childhood that won’t depart.

“What happened?” I finally get up the nerve to ask her.

“What do you mean?” she asks, but she’s just trying to avoid the question.

“Before I see your mom, could you tell me, what happened? Why were you adopted?”

“We’re almost there. Up this road about a mile, then take a right on Church Street,” she says, then puts both of her hands over her face.

“We should call your mom. I think we’re lost,” I say after following her directions. Church Street only goes for about a block before it ends at a set of open iron gates.

“No, this is it,” Ashley says, as we both read the sign in front of those gates: St. Mary’s Cemetery.

I pull the car off the road. Ashley walks into the cemetery; I follow a few feet behind. I hear the dirt crunching under our feet, and a strange sound coming from Ashley. I see, even from behind, her body shaking like a tall tree in a tornado. I’m just about to rush toward her when she kneels down next to a gravestone. She runs her fingers slowly over the cold marble letters, then speaks without a tear in sight. “I was only five when it started.”

“It?” I ask from my standing position.

“OxyContin,” she says. “They call it hillbilly heroin.”

“Ashley, I’m so sorry,” I say, then flash back on her run-in with Carl on the way home from the wedding, when he was yelling about hillbillies.

“It didn’t take long; Mom wasn’t that strong,” Ashley says, her voice wavering. “My mom was like this beautiful flower, but day by day, the petals kept falling away. She lost her job, then her friends, and even her family wouldn’t talk to her or help her out.”

“Except you,” I whisper, lightly touching her shoulder. She puts her hand on top of mine.

“No matter what, she protected me the best she could,” Ashley continues, squeezing down on my hand. “I only wish I could have done the same for her.”

“What do you mean?” I say, all the while trying not to cry; I’ve cried so many times in front of Ashley, but now I had to be the strong one. I needed to become Danielle the Defender once again.

“My dad had that same look in his eyes as Reid,” she answers.

“What are you talking about?”

“He was a user and abuser. He got Mom hooked, then left us. He’d come back, beat her, and then leave again. Until the next time,” Ashley snarls. “He was efficient. Dad did the maximum damage in the minimum amount of time, and I did nothing.”

“But you were only a child,” I remind her.

“I could have done something, anything,” Ashley says.

“I couldn’t save her.”

“Ashley, don’t be so hard—”

But she cuts me off. “She sold her clothes, all my toys, everything we owned. But she never sold the car, and she never did anything that put me in danger.”

She stops talking, like there are words inside her too heavy to speak.

“Ashley, I—”

“I came home one day from school when I was eight and she was dead on the floor of the trailer we were squatting in.” Ashley turns back to touch the gravestone again and si

ts down on the more brown than green cemetery grass. “The last petal in the wind.”

“I don’t know what to say.”

“There’s nothing to say.” She puts her hands on both sides of the gravestone. “It wasn’t her fault. It was Dad. It was the drugs. It was her love that destroyed us. I’ve been so angry at her for so long, for abandoning me.”

I’m silent, and for almost a minute, so is Ashley.

For all the time I’ve known her, she stayed strong through every disappointment. She never cried.

Then it happens. Ashley curls up against the gravestone, letting its weight support her. Years of dammed-up tears rush out of her for seconds, minutes, more, pushed forward by screams. Between the screams, I hear her whisper into the marble memorial, “Mommy, I’m gonna be okay now. I forgive you,” over and over again.

• • •

“What’s going on?” Evan says when I reach him on the phone at work.

“I need one more favor,” I say. I’m sitting in the Viper, talking on my cell. Ashley asked me to leave her alone with her mom. She’s making peace with her past; now it’s my turn.

“So you turned to your favor-rite person,” Evan says.

“When do you get off work?”

“In about two hours. What’s going on now?”

“Is Vic around your house?” I ask.

“Where else is he going to go?” Evan says.

“Can you meet us in a couple of hours at that rest stop again?” I ask. “Both you and Vic.”

“What’s going on?”

“Well, okay, I need two favors,” I say.

“Not thirty-one favors?” Evan cracks. It’s not funny, but I laugh to reward the effort.

“First favor is to meet us, and the second”—I pause, then continue—“is to not ask why.”

• • •

When Ashley finally comes back to the car, she looks older, and not just because of the dark circles under her eyes. She doesn’t say much, other than she’s ready to go home. I notice she says “home” and I wonder if she really means it. I know that I do.

We’re only waiting in the rest stop for about twenty minutes when Vic and Evan pull up. They’re driving their mom’s car, and Evan is still in his work clothes: my knight in shining armor is wearing a fugly red uniform, but his smile is cute and inviting.

Head Kick (The Dojo)

Head Kick (The Dojo) Duty or Desire

Duty or Desire Returning to Normal (Locked Out)

Returning to Normal (Locked Out) Things Change

Things Change Controlled

Controlled Friend or Foe

Friend or Foe Stolen Car

Stolen Car Heart or Mind

Heart or Mind The Franchise

The Franchise Triangle Choke (The Dojo)

Triangle Choke (The Dojo) #1 Out of the Tunnel

#1 Out of the Tunnel Chasing Tail Lights

Chasing Tail Lights Nailed

Nailed Combat Zone

Combat Zone Outburst

Outburst Barrier

Barrier Fight or Flee

Fight or Flee Doing Right (Locked Out)

Doing Right (Locked Out) Cheated

Cheated Guarding Secrets (Locked Out)

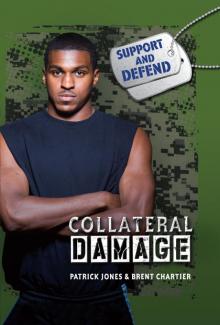

Guarding Secrets (Locked Out) Collateral Damage

Collateral Damage On Guard

On Guard Always Faithful

Always Faithful The Gamble (Bareknuckle)

The Gamble (Bareknuckle) Side Control (The Dojo)

Side Control (The Dojo) Bridge

Bridge Body Shot (The Dojo)

Body Shot (The Dojo) The Tear Collector

The Tear Collector Slammed

Slammed Drift

Drift Pass It Forward

Pass It Forward Target

Target Freedom Flight

Freedom Flight Taking Sides (Locked Out)

Taking Sides (Locked Out)