- Home

- Patrick Jones

Nailed Page 15

Nailed Read online

Page 15

“I just can’t do it, Mr. Douglas. I’m sorry for letting you down again, but I can’t concentrate on the play,” I say, my acting skills allowing me to hold back tears.

“I’m sorry to hear that,” he says. “How about being on the crew or stage manager?”

“No, I just can’t,” I say with all the strength I can muster.

“Bret, do you want to talk about what’s really going on?”

What I want to say is, “I don’t want to talk to anyone if they can’t take away this hurt, anger, and madness, and if they can’t do that, then screw ‘em!” It’s hard to talk about with anyone, even Dad and Alex. They both knew getting back with Kylee was wrong, and they both told me. I didn’t listen, since I couldn’t hear with my heart. I have so much to say, I stay silent.

“Okay. If you change your mind, the door’s always open,” Mr. Douglas says. “I mean that, I can’t figure out how to lock the thing.”

He pauses, waiting for the laugh that doesn’t come.

“Bret, you have to stay connected to something. To the theater, your music, something.”

“Why bother?” I’m not just defeated; I’m deflated and totally destroyed.

“Don’t talk like that, Bret,” he says with force. “Look at that stage over there. The roles I gave you up there were too small for your talent. Never deny that talent. Never deny yourself.”

“But when I am myself, I just get beaten up and I can’t fight back,” I confess.

“Everybody fights back,” he says.

“People like Dr. King never fought back,” I say, recalling what the posters from the Edmonds’s house taught me. I wonder how MLK would have handled a dream stealer like Sean.

“Yes, he did. He fought back using words and ideas, just not with violence,” he says.

“And he got assassinated for it,” I say, thinking how Kylee knocked me off.

“Bret, listen to what I’m saying,” Mr. Douglas says, his voice impassioned. “If you want to deal with the Bob Hitchings of the world, you can’t let them push you around.”

“Then what should I do?” I ask him.

“I don’t know. You’ll need to decide that for yourself,” Mr. Douglas says. “But I know just about the worst thing that you can do is to continue to do nothing.”

“Like Principal Morgan?”

“Mr. Morgan’s my boss. We disagree from time to time, but I don’t think he’s evil. And I don’t believe anyone’s all bad. I’m a big believer in gray areas.”

“What does that mean?” I ask with a shrug.

“Remember at the start of the year when everybody got a student handbook?”

I shrug. I’m totally lost, but always willing to loyally follow Mr. Douglas.

“Did you read it?”

“No, I thought I’d wait for the movie,” I say, still in touch with my sarcastic side.

“Well, we’re talking to Brad Pitt’s people about playing me, but that’s beside the point,” Mr. Douglas jokes, but I still can’t manage a laugh. “The book spells out what you can and can’t do at Southwestern. We have rules, and people have to follow them so things go smoothly.”

I serve up another shrug, this time without a side of snide.

“It’s a twenty-page book, so not every single situation is covered, right?”

If I shrug again, he’s going to think I’m having an epileptic seizure. “I guess not.”

“There’s right, wrong, and then there’s everything else. That’s the gray area. It’s where everyone makes choices, and it’s my job—and Mr. Morgan’s—to help students make the best ones. The best choices don’t benefit just the individual. We’re trying to have a society here.”

“You should teach social studies.” I get up to leave, and Mr. Douglas stands up as well.

“I have one more question to ask you,” he says, shaking my hand, man to man.

“What’s that?”

He gives me a light pat on the back, then delivers his line with an arched eyebrow and the comic timing that I can only hope one day to achieve. “Do you really think Brad Pitt is right for the part?”

Twenty-six

May 7, Junior Year

“Bret, what are you thinking?”

It’s Becca Levy. I expected and accepted this. “Look, let me explain—”

“I did you a favor and you stab me in the back?” she says, eyes wide with shock.

“No, listen, it’s not like that!” I put my name in to run against her for Student Council President, selling out just like Alex predicted. I needed to do what Kylee’s parents and Mr. Douglas and even Dad had told me: stand up for myself. I also need something to focus on 100 percent, aside from Kylee. That was Sean’s job now. When I saw him in my shoes and shirt, I knew Kylee was a case-closed issue. I couldn’t deal with the hurt, so I redirected it as best I could by righting another wrong. Morgan lied to me last fall. I never got my speech published. This is my chance to dust it off and shove my words up his ass in public. Kylee killed me, so there’s nothing Morgan can do to destroy a dead man walking.

“I’m very upset,” Becca says, then touches my shoulder. We’re standing by my locker, which is emptier now that I’ve cleared out any evidence of Kylee. My vision is clear now that it’s no longer clouded by her. One betrayal you can forgive, even it you can’t forget, but two are unforgivable and unforgettable.

“I don’t think I’ll win. In fact, Becca, let me be honest with you,” I say, trying to add some truth back into my life. “I don’t even want to win. If I win, I’ll quit and give it you. So you win, either way. This is really a favor for you.”

“Why are you running if you don’t want to win?”

“Because I want to make my speech,” I say, keeping my voice down.

“About what?” Becca asks, ugly tears fading, her pretty smile emerging.

“About what happens at this school,” I explain. “About how there’s money for a sports team, but not for a speech team. How people like Hitchings get a free ride, and coaches like King get away with being lousy teachers. I’m tired of this hypocrisy and my apathy about it.”

“Why in God’s name would you want to do that?” Becca asks.

“Because it’s the most fun I can have without being expelled,” I say glibly. This isn’t about winning, and in the end it isn’t about Kylee’s betrayal; it’s about finally fighting back. I wasn’t going to do it wrong again. I’d use my best tools and talents. I loved being onstage, but I was tired of acting the part of victim. I’m tired of everything and everyone pounding on me. I’m hurting worse than any person could hurt, I’m going to exploit it. I’m no nail, so screw them all.

“Bret, that sounds like a bad idea,” Becca says.

“That’s why it sounds so right,” I say, trying to make her laugh. “I need to take a stand.”

“You won’t need a stand, you’ll need a shield,” Becca jokes, and I laugh.

“I guess what I really need is courage.”

“It’s like the Wizard of Oz. You need courage and people like Bob need brains.”

“So which one of us needs a heart?” I ask, knowing that mine is too broken to function.

“Both you and Bob have plenty of heart. That’s the real problem I think.”

“Maybe, except for one small thing.”

“What’s that?” she asks.

“They hate me and Alex, and anyone who’s not like them,” I say. Then, for effect, I raise my voice to deliver an old prowrestling catchphrase: “I don’t hate the players, I hate the game.”

“If that’s your campaign slogan, then I don’t have anything to worry about, because I’m sure you won’t win.”

“Bring it on!” I shout. “The way I see it, you did me a favor getting the reformed Radio-Free Flint to play at the prom, so if I do win, I’ll be doing a favor for you in return.”

“Could you do me one more little favor then?” she says, her smile growing brighter.

“What’s that?” I ask.<

br />

“Since I got you to the prom, could you get me there?” she says with just the right amount of bashfulness. “I don’t have a date, and I thought maybe we could—”

“Becca, why would you want to be seen with me?” I ask to cover what would otherwise be my stunned silence, also wondering why she doesn’t have a date with Will. She’s smart, involved, and is way more popular than me. She’s no ten, but then again, neither am I. I learned that math lesson hard.

“Because you’re more than just a mental babe,” she says, speaking into the floor.

I pause again, the clashing of emotion ringing in my brain,heart, and every cell in between. “Okay, but you’ve got to promise me one thing,” I say.

“What’s that?” she says, with a prettier smile than I ever noticed.

“You won’t talk to the drummer!” I shout melodramatically.

“Cross my heart, Bret,” she says, asking no follow-up question, which confirms what I suspected. I’m guessing that Sean told Hitchings who probably told everybody he could about Sean walking in my shoes. “Are you sure about this?”

“One hundred percent!” I will show everybody while you can knock me down, I’ll get back up every time. When you’ve got nothing to lose, there’s nothing to do but win. “Deal?”

“Deal,” she says, shaking my hand, holding it longer than I expected. “Besides, what’s the worst that could happen?”

Twenty-seven

May 17, Junior Year

“We’ll hear first from Becca Levy, then from Bret Hendricks.”

Becca gets up as Mr. Popham, the student council sponsor, sits down. As Becca walks past me, I sense that she doesn’t seem the least bit self-conscious about people not liking what she says, who she is, or how she looks. She is pretty, but things onstage are about to get very ugly very quickly when I step up to the microphone. This is the final speech: we’ve done grades nine and ten, now my people, the juniors, get their chance to listen. In my speeches to those young ones, I was pulling punches. But this last one, with Hitchings, Bison, and Sean in attendance, is going to be what wrestler’s call a shoot: the truth and nothing but the truth.

I see Sean and do a half smirk, half smile. I’m still angry at him from when I handed over his money in the library, but it doesn’t stick. I can forgive him more easily than Kylee because I know what it is like to fall in love with her, to lose her, and be betrayed by her. We’ll always have that in common. I hope that along with learning the history of the United States, Sean’s also studying the history of the Destroyed Mates of Kylee Edmonds.When I met her, she cheated on Chad with me. The question for Sean isn’t who, but when. There’s no sense in even asking why.

“Bret Hendricks,” Mr. Popham says after Becca finishes, inviting me up to the microphone. After the applause for her dies down, I bring myself back to life.

“Flint Southwestern High School is run by a cult: the cult of jockarchy. It’s like any other cult. They wear their cult colors, worship at the altar of athletic achievement, and scorn those who do not believe as they do. A conformity cult of the privileged.”

I look over at Mr. Popham, who is frowning and now standing next to Mr. Douglas in the wings. I haven’t seen Morgan yet, but I expect I will. Mold King Cold isn’t in attendance; he probably has sports scores to read or plays to diagram.

“You walk in the door, and it hits you like a bloody nose: a red sea of Spartan jackets. It’s like walking in on a cult meeting. They have their secret symbols, their letter system, and their charismatic coaches who act as their leaders.” I’m calm, yet concerned, as I see the teachers in the audience getting uncomfortable. Some of the students are getting off on what I’m saying, while Hitchings, Bison, and the bullyboys look ready to attack. Sean just looks amused.

“They want everyone to believe as they do, and those of us who don’t are pushed out. They are the only majority cult, and I’m sick of them. Sick of the ball-throwing, puck-passing, track running thick skulls.” I’m slightly sidetracked by the sight of one of the teachers exiting out the back, sprinting toward the office.

“Let me make myself clear, I don’t mean everyone who picks up a ball belongs to this cult,” I say, winking at Will Kennedy. “In a larger sense, it’s not really about sports but about trying to have a great society rather this tyranny of the strong over the weak. I reject a world where some people push and take, while the rest of us try to pull together and give back.”

The room is getting loud, which bothers me not, since I’m shouting my long held words.

“Sports has to be about winners and losers, we all understand that, but that doesn’t mean we have to live that way off the playing field. Let’s stop bullying each other. Let’s stop acting big by putting others down,” I say, happy I’ve worked some of my mom’s philosophy into my speech, even though when she read it, she urged me not to give it, for fear I’d get in trouble. She’s right, trying to protect me as usual, but the real trouble is all around, and I refuse to ignore it any longer.

“Why should you vote for me? Simple: because I think many of you are as tired of what happens here at school as I am. I think a lot of you are fed up with a jockarchy who thinks the world revolves around them and harass those who are different.”

I look into the audience to see Hitchings’s face has turned as red as his letter jacket.

“Earlier this year, we did a play on this stage called The Crucible by Arthur Miller,” I tell the crowd, since probably no more than a handful in the audience attended the show. “The play’s about the Salem witch trials, but it’s really a metaphor about the 1950s and the McCarthy era, where everybody was supposed to conform. No one called this McCarthy guy on his bully tactics until a TV reporter named Edward R. Murrow took him on, but not by making a speech like this. Instead, Murrow let McCarthy destroy himself with his own vile and repulsive words.”

I reach into my pocket, and I think I heard a few people gasp in fear, but I pull out nothing more than paper filled with words, the most powerful weapon of all.

“I went to the library this morning and, with Mrs. Sullivan’s help, I found this article from Time magazine a few weeks after Columbine. This article quotes a member of that school’s jockarchy, but it sounds so similar to what I’ve heard here at our school.” I now look at my audience, asking them to agree to my vision by showing them the viciousness of the alternative.

“‘Columbine is a clean, good place except for those rejects. Sure we teased them. But what do you expect with kids who come to school with weird hairdos and horns on their hats? It’s not just jocks; the whole school’s disgusted with them. They’re a bunch of homos. If you want to get rid of someone, usually you tease ‘em. So the whole school would call them homos.’” I put the paper back in my pocket, then wipe the sweat from my brow.

Then, just as Morgan appears, and is about to shut off the microphone, I hit the finish.

“The enemy’s in this room, but we are not afraid to be ourselves. We are not afraid and we will not be victims any longer!” I shout, pointing right at Hitchings. I thrust my arms in the air, middle fingers curled inward, but in my heart aimed at the scarlet sea of water walkers. As I leave the stage, Morgan follows me, the veins in his neck bulging like ivy along his neck. I have no intention of dodging this bullet. This is about accepting responsibility.

Instead of yelling, he speaks firmly and almost with a smile. “I warned you before about mentioning Columbine. You almost caused a riot in there, and you know what that means?”

I don’t give him the satisfaction of even making eye contact.

“You’re suspended, Bret Hendricks, and pursuant to school policy, you’re expelled from school,” he declares.

“Why?” I know why, but I ask anyway; it’s tough to break old bad habits.

He slowly holds up one finger at a time, mouthing the words “One, two, three.”

I smile back at him and reply by holding up one finger. The middle one.

Twenty-eight

/> May 18–19, Junior Year

“Do the crime …”

“… do the time,” I say, finishing my father’s sentence as we finish off dinner. While my father’s loosened up on me somewhat, when it comes to issues of right and wrong, law and order, he remains rigid.

“Can I be excused?” Robin asks in her unvarying whine. For someone who used to be such a cute kid, she’s become a real middle school snot. Just like I was. However, unlike me, she’ll probably graduate from her school this year.

I tell my parents about the events of yesterday and the meeting tomorrow. I still can’t tell Dad that this suspension is my exit pass. He knows about this episode but not previous incidents.

“I told you this would happen,” Mom says; she’s quite upset.

“I’m going to call Mrs. Edmonds and ask for her help,” I say softly, almost ashamed.

“Do whatever you have to do, Bret,” she says curtly, getting up from the table.

“What’s that busybody going to do?” Dad asks.

“She told me she knew a lawyer who might help me.”

“Bret, I can’t afford a lawyer, and even if I could …” he says, looking away from me.

“Bloodsuckers.”

“It’s not that. What the hell were you thinking, trying to cause a riot?”

“That I was tired of not fighting back.”

“Still,” my father mutters in a tone of voice that tells me he can see my point.

“Don’t worry about the money,” I reassure him. “He’s pro bono from the ACLU.”

“No good liberal do-gooders!” Dad says, but he’s smiling about it.

“I’m going to call,” I say, getting up from the table. I decide to take a pass through the kitchen, where Mom’s washing the dishes. “Mom?”

“I’m busy, Bret,” she says, keeping focused on the task at hand.

“Look, I’m sorry. It’s not that I like Mrs. Edmonds better than you.”

“Don’t be silly,” she says dismissively, her body language telling a different story. The soapy water ripples as her hands are submerged and shaking.

Head Kick (The Dojo)

Head Kick (The Dojo) Duty or Desire

Duty or Desire Returning to Normal (Locked Out)

Returning to Normal (Locked Out) Things Change

Things Change Controlled

Controlled Friend or Foe

Friend or Foe Stolen Car

Stolen Car Heart or Mind

Heart or Mind The Franchise

The Franchise Triangle Choke (The Dojo)

Triangle Choke (The Dojo) #1 Out of the Tunnel

#1 Out of the Tunnel Chasing Tail Lights

Chasing Tail Lights Nailed

Nailed Combat Zone

Combat Zone Outburst

Outburst Barrier

Barrier Fight or Flee

Fight or Flee Doing Right (Locked Out)

Doing Right (Locked Out) Cheated

Cheated Guarding Secrets (Locked Out)

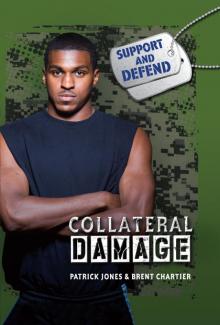

Guarding Secrets (Locked Out) Collateral Damage

Collateral Damage On Guard

On Guard Always Faithful

Always Faithful The Gamble (Bareknuckle)

The Gamble (Bareknuckle) Side Control (The Dojo)

Side Control (The Dojo) Bridge

Bridge Body Shot (The Dojo)

Body Shot (The Dojo) The Tear Collector

The Tear Collector Slammed

Slammed Drift

Drift Pass It Forward

Pass It Forward Target

Target Freedom Flight

Freedom Flight Taking Sides (Locked Out)

Taking Sides (Locked Out)